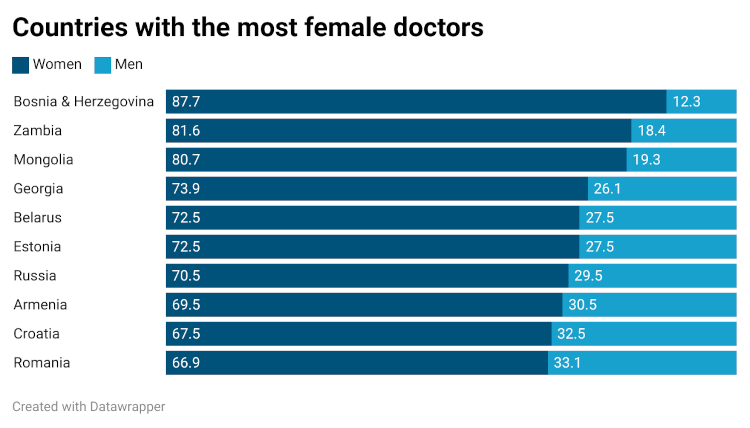

Most of the global healthcare workforce is female – but most of the doctors and senior nurses are still men

Women represent around 70 per cent of the global healthcare workforce, but in most countries, men continue to make up the majority of medical doctors. Even in roles where women predominate, such as nursing, men typically fill more senior positions (in the UK, research by the Royal College of Nursing shows that only a third of senior nursing roles are held by women). Not only does this mean that women in medicine are concentrated into lower status and lower paid roles, research also shows that gender balance in clinical staff can affect patient outcomes and satisfaction. Studies suggest that female doctors show more empathy, spend more time with their patients, and are more likely to address mental health concerns than their male counterparts. Many female patients also prefer to be treated by female physicians.

One study even revealed that female patients have a lower rate of mortality when treated by a female doctor. Over the past two decades, the proportion of female doctors has increased in many countries. In England, female doctors make up 48 per cent of the workforce, in Scotland it’s 53 per cent. In some places, the balance has even reversed. Here, we look at the countries with the highest percentage of female medical doctors (including generalist and specialist medical practitioners).

Countries with the highest percentage of female doctors

1)  Bosnia & Herzegovina – 87.7%

Bosnia & Herzegovina – 87.7%

2)  Zambia – 81.6%

Zambia – 81.6%

Overall, the African continent suffers from a shortage of healthcare workers, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. One key driver of this shortage has been the mass emigration of African health workers to countries such as the UK and the US; an OECD census in 2007 revealed that Africa has the highest percentage of migrating women with a tertiary education. The African region has a smaller proportion of female doctors than the global average – just 28 per cent. However, several countries have achieved gender parity, including Benin, Mozambique, Senegal, South Africa and Tunisia. Others, such as Zambia, where just 18.45 per cent of doctors are men, and Madagascar, where 70.8 per cent of doctors are women, have managed to reverse the trend.

3)  Mongolia 80.7%

Mongolia 80.7%

In Mongolia, women are the majority in all areas of healthcare. From doctors and nurses to radiologists and lab technicians, they make up 82.3 per cent of the workforce. This ‘reverse gender gap’ goes beyond the healthcare sector too, as more and more rural families are sending their daughters to schools in the cities. On average, Mongolian women are more educated than men (60 per cent of university graduates are female), they are less likely to be unemployed, and they live longer – by up to a decade.

4)  Georgia – 73.9%

Georgia – 73.9%

5)  Estonia – 72.5%

Estonia – 72.5%

Estonia witnessed a dramatic loss of physicians, many of whom fled or were imprisoned or killed, during its Soviet occupation following World War II. By the early 1990s, its historically male medical workforce had become 77 per cent female.

6)  Belarus – 72.5

Belarus – 72.5

7)  Russia – 70.5%

Russia – 70.5%

Since the 1950s, women have comprised approximately 70 per cent of doctors in Russia. During the Soviet era, as physicians became state employees, medicine lost a lot of its prestige and became one of the poorest-paying professional occupations. At the same time, women were encouraged to work in medicine, resulting in the current high number of female doctors. Despite this, few Russian female physicians can be found in specialties such as surgery and academic medicine, and on average Russian women in medicine earn 6 per cent less than their male colleagues.

8)  Armenia – 69.5%

Armenia – 69.5%

9)  Croatia – 67.5%

Croatia – 67.5%

10)  Romania – 66.9%

Romania – 66.9%

Countries with the lowest percentage of female doctors

Of all the OECD member countries, Japan has the lowest proportion of female doctors at just 10.2 per cent. The low number of women in medicine reflects the prevalent societal belief that careers and motherhood cannot be easily combined. It’s a barrier faced by female physicians in many other countries; roughly half of all entrants to Indian medical schools are women, but the challenge of balancing long hours and family responsibilities means many don’t enter the profession. In 2018, Tokyo Medical University admitted to manipulating women applicant’s entrance exam scores for years to restrict the number of female doctors, in part because they were performing better than male applicants.