Discover more about Mayotte and other nearby regions devastated by the impact of cyclones amid human-induced climate change

By

Today, Africa experiences four times as many storms – and more than double the amount of cyclones – than it did back in the 1970s. As oceans warm and global temperatures rise, the frequency of heavy rainfall events in most of tropical Africa is set to be a continuing trend, a scenario that will wreak havoc upon already struggling communities, economies and infrastructure.

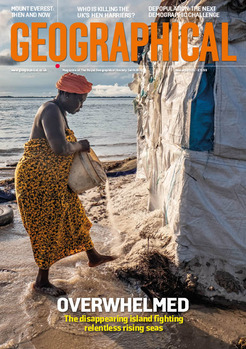

With the recent Cyclone Chido devastating the islands of Mayotte along with other nearby southeastern African countries, here we examine the devastation of the region’s latest cyclone as well as how these extreme weather events deepen existing challenges faced by particular nations.

Where is Mayotte?

Mayotte is a French overseas department located in the Mozambique Channel in the the western Indian Ocean, and made up of two islands, Grande-Terre and Petite-Terre.

The region is densely populated, with more than 300,000 residents and a predominately young population. More than 40 per cent of its residents are under the age of 15, while just 12.5 per cent are 45 or older. According to the French interior ministry, more than 100,000 of Mayotte’s population are undocumented migrants.

Mayotte is one of the poorest parts of France and depends on the financial support given to it, with three out of four residents living below the poverty line. Compared to France’s unemployment rate of 7.4 per cent, Mayotte’s is starkly higher at 37 per cent. Such stark poverty within the region only further exacerbates the impact of a major storm like Cyclone Chido, as residents struggle to recover with limited resources.

Where did Cyclone Chido hit?

On Saturday, Mayotte was hit by Cyclone Chido, the worst cyclone in the region in almost a century. Winds of more than 124mph (200km/h) were recorded, leaving buildings and homes destroyed as well as internet access largely out. It is feared that close to 1,000 people may have been killed in the natural disaster.

As well as Mayotte, the nearby islands of Comoros and Madagascar, along with Mozambique, were hit by the Category 4 Cyclone Chido last week.

France has already begun to mobilise support including emergency equipment, rescue teams and medical personnel to bolster rescue efforts. Such support has already been made difficult by the fact that the airport’s control tower experienced such significant damage that it could not be used, meaning only military aircraft have been able to land.

Cyclone impacts on southeast Africa

Cyclone Chido is just one storm representing the vast and growing trend of cyclone activity in southeast Africa. A plethora of scientific evidence suggests the region is bearing the brunt of human-induced climate change, with some scientists declaring it is already a ‘hotspot’ for tropical storms and cyclones.

In five back-to-back storms that hit southeast Africa back in 2022, climate change made extreme rainfall heavier and more damaging – a finding consistent with scientific understanding of how climate change influences rainfall. As the atmosphere gets warmer, more water accumulates inside it, contributing to a greater frequency and intensity of heavy rainfall.

This is a trend already expected to continue, with further research suggesting human-induced climate change will contribute to future cyclones – not just in southeast Africa, but in other places across the world – becoming more severe (above Category 3).

The study model predicted areas to be hard hit by these frequent, more severe storms, including Cambodia, Laos, Mozambique and Pacific Island Nations like the Solomon Islands and Tonga.

In particular, Mozambique has already faced devastating consequences of this trend with the recent Cyclone Chido, but has also endured increasingly frequent tropical storms over the past few years too.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

In 2019, Mozambique was faced two devastating cyclones in the same season for the very first time: Cyclone Idai and Cyclone Kenneth. Combined, these cyclones killed more than 600 people and injured 1,641, destroyed just under 225,000 homes and left 2.5 million people in need of humanitarian services across Mozambique, but also in Zimbabwe and Malawi.

Since 60 per cent of Mozambique’s population lives on its huge, 2,700km stretch of coastline – and this is where the country’s largest cities are – such weather disasters can significantly threaten a large proportion of infrastructure, including businesses, homes and vital services such as hospitals, and have major impact on its economy. It is within the top ten countries most vulnerable to climate change and natural disasters – so much so that without intervention and adaptive measures, the country could face 1.6 million people falling into poverty by 2050.

And last year, Cyclone Freddy hit Mozambique twice in the space of just one month – impacting more than 390,000 hectares, around 132,000 houses and an estimated 123 health facilities.

The same storm also devastated Malawi, displacing more than half a million people and killing at least 500 with extreme rainfall, catastrophic debris flows and flooding.Such flooding also exacerbated the risk of waterborne diseases in the country, exacerbating the fact that prior to the cyclone, more than 50,000 cases of cholera were reported and at least 150 deaths from the disease.

In Malawi, the effects of extreme weather events like cyclones are also made more severe due to the pre-existing high rates of deforestation, as well as land and watershed degradation, all of which contribute to increased flood and landslide risk. The country also has a high level of inequality, so disruptions to livelihoods following cyclones will likely widen the gap between the poor and the well-off.

Even storms that are relatively weaker – like Storm Filipo, making landfall in Mozambique earlier this year – can bring about devastating impacts. High wind speeds and heavy rainfall decimate crops, leaving many people without food. In addition to this, dry spells and flash floods in the country – exacerbated by climate change – further hamper the ability to produce adequate food and plummet individuals into food and money crises.

Poor road conditions in both countries make it difficult for aid to be given to residents, as well as slowing the process by which those threatened with a cyclone risk can evacuate safely.

To support southeast African countries amid the rising frequency of storms, methods such as disaster risk reduction systems, along with early warning system installations, are being proposed as potential solutions. As well as this, community risk mapping will ensure an adequate level of preparedness for when natural disasters like cyclones strike.