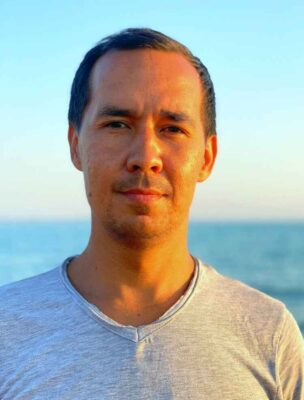

Biologist Albert Salemgareyev’s conservation work has helped bring the saiga antelope back from the brink, winning him the 2023 Whitley Award

By

The saiga antelope is a strange looking animal. Their large, bulbous noses have evolved to filter out dust during the hot, dry summers and to warm the cold winter air. It makes them well-adapted to live on the steppe, where they have survived since the ice age.

One of the oldest living representatives of the ‘mammoth fauna’ (a group that includes the mammoth, the woolly rhinoceros and the cave lion), the saiga once roamed the whole Eurasian continent. Today, 98 per cent of the world’s remaining population can be found in Kazakhstan.

By the early 2000s, hunting, habitat loss and disease had pushed the species to the brink of extinction. ‘The saiga population had reached a critical level, roughly 21,000 individuals remained across the whole of Kazakhstan,’ says Albert Salemgareyev, lead specialist at the Association for the Conservation of Biodiversity of Kazakhstan (ACBK). It’s a vast area, he adds, which made the small herds extremely hard to find.

Salemgareyev is a biologist, and a specialist in GIS and wildlife monitoring. He was born in a village on the edge of Naurzum Nature Reserve, a 3000-square-kilometre area of open steppes and pine forests in northern Kazakhstan, home to the steppe polecat, the corsac fox, the long-eared hedgehog and, of course, the saiga antelope.

Growing up, Salemgareyev learnt about the threats facing the antelope from his parents. ‘The saiga is an iconic species for the people of Kazakhstan because the Kazakhs were historically nomadic, just like the saiga,’ he says. ‘They are a symbol of freedom.’

The saiga are equally important to the local landscape. ‘We don’t have many ungulates in Kazakhstan, especially in the steppe grassland,’ says Salemgareyev, ‘and the steppe needs grazers like the saiga.’ This keystone species plays an important role in managing the natural vegetation of the ecosystem, helping certain plant species to grow and creating habitats for other animals. Their grazing habits also help to reduce the risk from grassland fires, a growing problem across Central Asia.

Since 2009, Salemgareyev has worked to monitor and reverse the decline of the saiga antelope populations. His research has resulted in data and maps that have informed the state rangers that patrol against poaching, and improved understanding of saiga migration patterns and the barriers they face. ‘We have also used the data to create and extend existing protected areas in Kazakhstan, ensuring protection for an additional five million hectares of land.’ New sites include Bokey Orda State Nature Reserve and Ashiozek State Nature Sanctuary – both important grazing grounds in western Kazakhstan – as well as the first ecological corridor between two protected areas.

The saiga populations of Kazakhstan have since made an incredible recovery and now number 1.3 million individuals. As a result of his hard work and dedication to their conservation, Salemgareyev has been awarded the 2023 Whitley Award by the Whitley Fund for Nature, a UK charity that supports grassroots conservation leaders in the Global South. The £40,000, which was presented on 26 April at the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), will fund a new project that aims to better understand the nature of the emerging conflict affecting the Ural saiga population and the estimated 300 pastoralists living in the landscape around the new Bokey Orda and Ashiozek protected areas.

As populations have rebounded, some areas have seen saiga and livestock competing for resources. ‘The problem is the region lacks sufficient water resources,’ says Salemgareyev. ‘The steppe’s rivers and streams depend heavily on autumn and winter precipitation. If there’s not enough snow or rain then the water just evaporates, it can be gone by the middle of summer.’ Salemgareyev explains that the saiga are wandering onto farms in search of water that pastoralists put out for their livestock, sometimes leaving little behind. He plans to use the award to map the major water resources and monitor the movements of both livestock and saiga in 15 hotspots on the outskirts of the new protected areas, in search of a sustainable solution for both people and the ecosystem.