For millennia, pastoralism has supported millions of people living in some of the world’s harshest environments. But now, as climate change makes the need for this traditional, low-impact, sustainable means of human co-existence with animals and landscapes ever more crucial, it also poses its biggest threat

By Mark Rowe

Pastoralism is a system that supports livelihoods on areas known as drylands or rangelands, which account for more than half of the world’s land. The image that comes to mind may well be of reindeer in the Arctic, but similar semi-wild, communally held livestock systems exist on every continent except Antarctica and involve the seasonal movement of sheep, goats, cattle, horses, yaks, camels and other animals in the never-ending quest for water and forage.

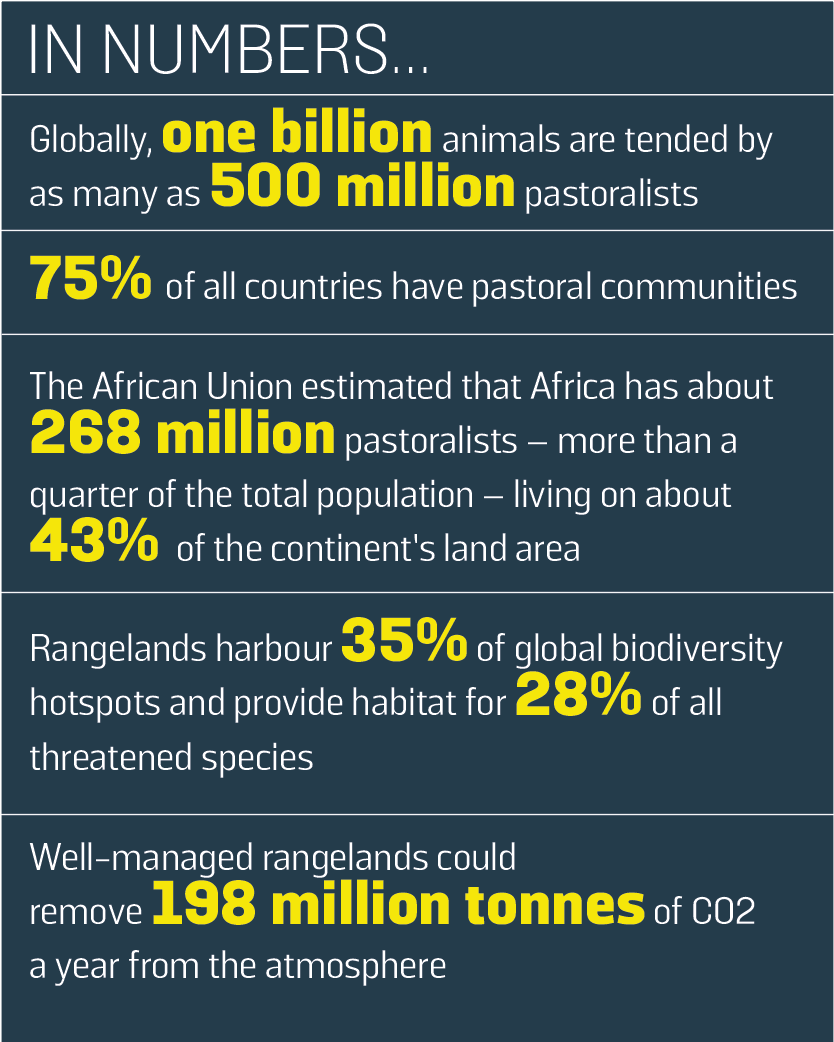

Although some one billion animals are reckoned to be herded by up to 200 million pastoralists – according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) –

pastoralism is patchily distributed and generally involves isolated movements of people and animals in small herds; it’s a barely visible, often forgotten, herding culture. Pastoral systems are incredibly diverse. Some pastoralists are fully nomadic and permanently on the move. Others are semi-or permanently settled. Some move long distances between regions; others move animals daily or seasonally over a smaller area. Pastoralism can involve camel-keeping in the deserts of Rajasthan and Gujarat or upland herding in Himachal Pradesh and the Karakoram mountains. In South America, pastoralism survives in some isolated areas, including high-mountain llama and alpaca production. Across South Africa, Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe, although the vast herds of earlier times no longer exist, livestock, notably cattle, are still central to agro-pastoral systems, retaining major social and cultural significance. ‘Pastoral peoples have their own languages and cultures, which form part of the world’s cultural heritage, to be appreciated as we do for any other culture,’ says Mauricio Vazquez, research lead based at ODI for the programme Supporting Pastoralism and Agriculture in Recurrent and Protracted Crises.

Low-impact but highly politicised

Yet for such a low-level, literally grassroots practice, pastoralism can attract a lot of ire. Pastoralists are accused of degrading land, overgrazing, cutting down trees and sustaining methane-and carbon-rich meat production. The case for pastoralism is nuanced, which makes it all the more difficult for advocates in a world where the loudest arguments tend to call for either universal intensive farming on the one hand or an exclusively vegan diet on the other.

‘Pastoralism is subject to a lot of confusion and misunderstanding,’ says Professor Ian Scoones, a fellow at the Institute of Development Studies. ‘The problem is that people try to lump all livestock production together. Too often people generalise and seek simple solutions and don’t understand the concept.

‘Like any system, if it’s used too much you get biodegradation, so pastoralism needs to be managed – but not to be eliminated,’ he continues. ‘It’s good for the environment and good for plants; it’s an important ally of conservation and biodiversity. Degradation usually happens when pastoralism is pushed out by development or farms – that’s not the fault of the livestock or the system.’

Climate friendly

Pastoralism makes use of variable landscapes by moving animals and managing grazing. The practice, depending on careful herding and mobility, and adapted to the variety of wild species and the ebb and flow of the seasons, may have many answers for how to feed developing nations and mitigate climate change through low-intensity land use. For example, pastoralism can provide protein on rangelands where crop growing is difficult, manage wildflowers and biodiversity by herding animals around, and sequester carbon. ‘Pastoralism uses a mixture of grazing and burning that has been established over millennia,’ says Scoones. ‘By grazing, you get a greater variety of grasses, the deposition of manure and the dispersal of seeds through transhumance.’

Pastoral grazing is managed through deliberate herding, enabled by close, caring interactions between humans and animals. It has co-evolved with rangelands, savannas and open woodlands that are essential habitats and important sites of biodiversity. For a healthy diet, grazing animals need a balance of different plants. Herders enable this by letting the animals forage across environments that vary in altitude, moisture and vegetation type. In contrast, industrially produced animals must rely on imported feeds such as soy, which may displace production of food crops. As Vazquez points out, ‘[biodiversity] is likely to be much higher than if the range is turned over to sugarcane production’.

Mobile livestock production can be not just climate neutral but climate positive, according to the FAO. ‘Because pastoral systems mimic and replace wildlife systems, they may not add to total greenhouse gas emissions,’ says an FAO spokesperson. ‘While all ruminant livestock produce methane, pastoral systems can build up soil carbon, reducing the total impact. They promote rangeland health by improving soil fertility, conserving biodiversity and managing fires.’

Protein where no other is to be found

Animal-source foods provide valuable protein and also, importantly, concentrated and affordable micronutrients that are crucial for young children and pregnant and breast-feeding mothers. Pastoral systems make this nutrition available in areas where crop agriculture is difficult, such as highlands and drylands.

‘Pastoralism is a viable form of production that takes place on land that is otherwise more or less unusable,’ says Scoones, who points out that the Global North is where wealthy nations consume far more meat, while many of the world’s poor suffer from nutritional deficiencies and their consequences.

‘It’s key not just for protein but for milk and other nutrients – folates, vitamins that you can’t easily get from a plant-based diet – that vulnerable people will otherwise simply not be able to access,’ he says.

Meat and methane

Livestock contributes around 14 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Although pastoralists contribute a miniscule proportion of this, they’re often entangled in international calls to cut meat-related methane emissions.

‘The problem is this blanket approach that we need to cut back meat to save the planet,’ says Scoones. ‘Proponents are very voluble, but their argument is simplistic. Yes, absolutely, we must cut back, but in the Global North we eat more meat than we need and often produce it unsustainably. Pastoralism produces less meat, more sustainably. Too often, climate debates fail to account for the way in which pastoralism can provide nutritious, protein-rich meals to often the most marginalised people. Instead, they focus narrowly on emissions per animal.’

‘Intensive, contained, factory-farm production is very different from extensive or pastoral systems,’ adds the FAO spokesperson. ‘Lumping them all together in a single anti-livestock narrative either lets industrial producers hide behind more benign systems of production, or forces marginalised pastoralists to bear the costs of a transition to a lower-carbon future, despite having contributed virtually nothing to climate change.’

Scoones points to studies in Kenya that measured methane produced by animals grazing on rangelands, which show much lower emissions than are assumed in standard models used for global assessments. The FAO agrees. ‘Estimates from many international organisations massively overestimate emissions from African animals grazing on natural rangelands,’ says the FAO spokesperson. ‘Emissions experiments are usually carried out with animals bred for industrial production. They ignore the genetic diversity and adapted physiology and behaviour of pastoral animals, as well as the local knowledge, herding and training skills that are the core of pastoralism.

‘In mobile pastoral systems, indigenous breeds are adapted to eat highly nutritious forage combined with rough grass, including vegetation with a high tannin content,’ they continue. ‘These feeding practices are not available to contained animals but can reduce methane production significantly.’

IUC/UNEP

Under threat from climate change

Given that rangelands are already characterised by frequent dry spells that can turn into prolonged drought, pastoralists are among the world’s most vulnerable people to climate shocks and stresses. Climate change is now making weather even more unpredictable, with erratic rainfall and temperature increases. On top of this, desertification leads to land degradation and falling levels of soil organic carbon.

In 2022, the World Bank approved a US$142 million credit to Uzbekistan for a project aimed at restoring degraded forest and transboundary lands. Land use in Uzbekistan is usually as rangelands, which occupy more than half the country’s surface. Extreme weather such as droughts or decreasing precipitation are key drivers of degradation in the country, reducing water reserves (although uncontrolled harvesting of wood and non-wood productions, encroachment and expansion of agricultural land also play a role). As Uzbek pastoralists and other livestock producers struggle with scarce resources, they’ve adapted their herd size to survive, keeping small multi-species flocks of three to five cattle and/or three to six sheep and goats in a subsistence model. This puts pressure on livelihoods and food sources: bigger flocks would be difficult to raise under those conditions, while smaller ones won’t be enough for the household to make a living.

Green grabbing

The growth of infrastructure – especially roads and other transport corridors – is transforming large areas of marginal land in some regions into new investment frontiers. ‘Pastoralists are subject to arbitrary expropriation of land that they have been using for centuries,’ says Vazquez. ‘Most of what threatens pastoralists comes from deliberate action by governments and corporations that are at best indifferent to pastoralists and at worst actively hostile.’

With sparse populations, pastoral areas are often seen as empty, idle wastelands thirsty for investment. Vazquez is concerned that pastoralists’ governance

and tenure systems in regions such as East and West Africa are struggling to cope with new and/or intensified pressure for natural resources. Valuable pastoral areas, such as riverine grazing zones, are targeted for agriculture, tourism or wildlife and conservation use.

Globally, around one billion hectares of rangeland has been earmarked for restoration, as conservation enclosures or for carbon-sequestration and -trading programmes. ‘Even now, the places inhabited by pastoralists are the ones with rich biodiversity,’ says camel conservationist Ilse Köhler-Rollefson of the League for Pastoral Peoples. ‘One of the most famous pastoralist advocates, Jesus Garzon-Heydt from Spain, once said to me that “if you have pastoralists, you don’t need national parks” and I think he is quite right. Ironically, these areas then become selected to be turned into national parks, which usually results in eviction of the pastoralists.’

Pastoralists active on the drylands of Central Africa have regularly been blamed for the encroachment of the Sahara Desert and this has led to pushes to re-green dry areas. One such scheme offers a certificate of ‘protected savannah’ for a donation to an environmental charity or programme that promises to ‘offset’ your climate emissions, through planting biochar feedstock plantations on ‘under-used marginal’ land in East Africa.

The FAO is gravely concerned about such moves. ‘Some conservation and rewilding approaches fail to consider the role of local populations in nature conservation,’ says the FAO spokesperson. ‘They neglect the socioeconomic context; they ban grazing and further decrease local access to land.’

Scoones dismisses what he calls ‘fortress conservation’, a concept that he says buys into the ‘half Earth’ philosophy, whereby were half the Earth saved for conservation and the other half set aside for intensive development, all would be well. ‘Essentially, you put up a big fence and hope that behind that fence the ecosystem will be fine. That shows poor understanding – it’s almost old-fashioned colonialism. This northern vision of conservation can be very damaging. If we

don’t think hard about how we use conservation it can be dangerous.’

General encroachment is a ‘far, far bigger’ issue, according to Köhler-Rollefson. ‘I see how customary grazing areas are continuously being alienated and subverted,’ she says. ‘Green energy projects, wildlife conservation, irrigation agriculture, fencing, construction all eat into pastoralist areas. Sometimes I think by doing that, humanity is sawing off the branch on which it sits.’

Grazing with trees: Silvopastoralism

Global demand for food, including animal-source food, is forecast to increase by 1.4 per cent per year over the next decade, while demand for timber and other forest products will also increase, according to both the FAO and the OECD. The FAO warns that in order to cope with the increased appetite, forests and pasturelands will be reduced to make way for cropland.

Yet trees in dryland forests and woodlands provide essential ecosystem services such as animal feed, timber, fruit, shade and regulation of soil and water cycles. They are vital for biodiversity and cultural services, linking people – frequently pastoralists – and trees. The FAO calculates that about 15 per cent of animal feed in the Sahel depends on trees, so growing more of them in such areas may be part of the solution. An FAO study of silvopastoral systems (essentially grazing among trees) found that dryland regions that introduced trees showed impressive results. Soil temperatures tend to be lower, encouraging biodiversity and nutrition. In Latin America, pasture-based cattle farms increased forage production by more than 175 per cent and milk production per hectare by more than 75 per cent after incorporating trees into the local environment. In Iran’s semi-arid Oshtorankuh Protected Area, communities used forest and rangeland by-products (including medicinal plants, fuel wood, fodder and shelter, and tree seeds for food) to generate additional income.

Lessons for climate action

The counterargument is that pastoralism uses traditional knowledge and practices to help animals and people live together in uncertain and unpredictable environments. As Vazquez puts it: ‘Pastoralists manage risks better than most communities and there is lots to learn from them’. Over millennia, pastoralists have learned to live with and from uncertainty. Generally, they minimise external inputs, shorten value chains and have lower transport and infrastructure costs. ‘Pastoralism is by its very nature innovative,’ says the FAO spokesperson.

This offers lessons for us all, argues Scoones. ‘Pastoralists have unique knowledge and skills to respond flexibly and effectively in turbulent conditions,’ he says. ‘Principles that pastoralists follow in responding to uncertainty, ignorance and surprise therefore have much wider relevance for policy frameworks. All of us can learn from pastoralists, whether in relation to pandemics, climate change, migration, natural disasters or financial volatility.’

Vazquez points to the logical consequence of interfering with a system that, in essence, is in tune with the environment. ‘This is problematic because the land converted often comprises key grazing areas close to reliable water sources. This leads to a cycle of reduced access to resources and increased vulnerability to shocks or risks such as droughts.’

Camels helping to climate-proof India

On a small scale in Rajasthan, the League for Pastoral Peoples (LPP) has been trying to reinvigorate camel pastoralism by building a market for high-value milk from nomadic herds. India has just 300,000 camels, compared to 193 million head of cattle and 149 million goats. The LPP is supporting ways to scale-up camel milk production as an alternative for people turning vegetarian out of animal welfare concerns.

This has led to the local revival of camel herding and re-appearance of camels in the landscape. ‘They do really fine during droughts, so they could and should be an important means of climate proofing,’ says Ilse Köhler-Rollefson, who has spent the past 30 years living with and studying Raika camel herders in Rajasthan, India. ‘With just a bit of investment, this approach could be expanded throughout the state and would bring enormous benefits.’

The camels, along with other pastoral animals, play a vital role in not only milk but meat production and provide organic fertiliser. ‘I regard them as the backbone of the country’s food security,’ says Köhler-Rollefson. ‘If they continue to get squeezed out of the system, it will be an ecological disaster, unravelling the traditional synergy between crop cultivation and pastoralism.’

Lions and giraffes or food?

Scoones feels a more sustainable ‘whole Earth’ approach is needed, whereby all areas are integrated with a balance between conservation and development ‘with livestock a part of that. You can’t simply turn over the plains of East Africa to the lions and giraffes. You have to have livestock there because of the many millions of people who depend on them and what they produce. You can’t solely rely on ecotourism for income.’

Traditionally, pastoralism has suffered from poor understanding, marginalisation and exclusion from dialogue. Scoones hopes that the annual climate COP process and subsequent international meetings will embed the principles and rights of pastoralism and the land rights of its practitioners into policies and wider consciousness. ‘Pastoralists don’t have access to these kind of forums, so their voices are not the ones that get heard,’ he argues.

Yet precedent doesn’t point definitively to an optimistic outcome, suggests Köhler-Rollefson. ‘We extensively campaigned for livestock keepers’ rights in the 2000s, arguing that it is pastoralists who manage and conserve livestock biodiversity, but we finally gave up – there was no progress,’ she says. She also describes as ‘disappointing’ efforts to engage with the Nagoya Protocol of the Convention on Biological Diversity. ‘But there is no doubt that the value of pastoralism has come into much clearer focus in the last few years.’

Even so, supporters of pastoralists must be careful not to sound too censorious, warns Vazquez. ‘I’m not sure that you can or even should “safeguard” pastoralism as a way of life. It’s people’s choice and they may choose to leave it,’ he says. ‘It’s not a heritage theme-park to be conserved, it’s a dynamic and ever-changing economic system and culture. You have to safeguard people’s rights to property and that should include the property of the pastoralists – their range – so that the basic economic conditions for pastoralism to work are protected to the same degree as everyone else’s livelihood.’

Advocates need to keep plugging away, suggests Scoones. ‘At the moment, a lot of things are heavily weighted against pastoralism. It’s a long-term part of the answer and needs to be more central to the way we approach the issues we face.’

Vazquez drily muses on whether those so keen to displace pastoralists in the name of nature would do the same back home. ‘I wonder how many campaigners are also advocating for no-go nature reserves in the towns where they live, and are willing to give up their homes and move elsewhere? Or does biodiversity only matter on other people’s land?’