According to the Global Maritime Wrecks Database, more than 250,000 shipwrecks – dating from 2200 BCE to the present day – litter the ocean floor, but research by UNESCO estimates the number is closer to three million, most of which remain undiscovered

By

Wrecks represent a treasure trove of historical data and artefacts, scrap metals to be salvaged (often illegally) and reused, and sometimes real treasures too. At the moment, the Colombian government is working out the best way to raise the San José, an 18th-century Spanish galleon that sank within the country’s waters. Some £3.5 million has been invested in recovering and conserving the wreck and its contents – including gold coins and jewels – but some scientists believe that shipwrecks are just as valuable when left at the bottom of the sea.

‘A wreck not only has all of the history associated with it – the story of the disaster or the lives that have been lost – it also becomes part of the environment,’ says Kirstin Meyer-Kaiser, a benthic ecologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in the USA. ‘One archaeologist with whom I regularly collaborate likens a shipwreck to any other artefact found in any historical museum, except that it’s not preserved behind glass. Instead, it’s subject to erosion, it’s impacted by waves and natural hazards. There’s a two-way feedback between the wreck itself and the environment around it.’

Shipwrecks offer a window into the ways in which the world’s oceans and coastlines are rapidly changing. In the Mississippi River delta, scientists are using them to track the movement of hazardous mudslides, which are known to pose a risk to gas and oil infrastructure. One 10,000-tonne oil tanker off the coast of Louisiana, torpedoed by a German U-boat during the Second World War, has moved almost 11 kilometres over the past 80 years, dragged by a shifting layer of mud.

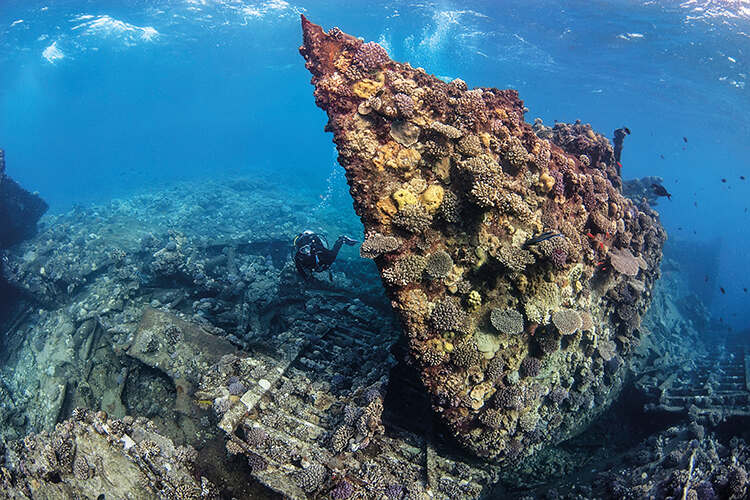

Shipwrecks can also inform our understanding of how marine organisms will adapt to future ocean sprawl – offshore infrastructure from wind farms to undersea communication cables. Shipwrecks are known to create new habitats for many marine species; studies have shown that wrecks in the Gulf of Mexico harbour higher levels of biodiversity than natural boulder reefs. ‘Any anthropogenic object that we put into the ocean eventually becomes a habitat,’ says Meyer-Kaiser, but some structures may be less hospitable to marine life than others.

While researching in Palau, an archipelago in the western Pacific Ocean, Meyer-Kaiser noticed a striking difference between two Second World War wrecks. One, a shipwreck, was teeming with corals, but the other, a military plane wreck, was virtually devoid of life. ‘I believe that this might have something to do with the trace metals in the water,’ she says. When she tested for trace metal concentrations in coral tissues taken from the ship, she found much higher levels of iron – an important micronutrient – whereas corals sampled from the plane contained much more aluminium. ‘And guess what,’ she explains, ‘aluminium is toxic.’

Despite the wrecks’ value to science, Melanie Damour, a marine archaeologist at the US Bureau of Ocean Management, cautions that they still need to be protected, even from researchers. ‘I don’t want to open Pandora’s box and say, “Everyone must go study shipwrecks”,’ she says, describing wrecks as a ‘non-renewable resource’.

Shipwrecks face a growing number of risks, from ocean currents and acidification to warming waters that promote the spread of destructive, invasive species such as shipworm. At the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, off the coast of Boston, USA, the locations of more than 200 shipwrecks have largely been kept secret (Meyer-Kaiser says she had to sign a non-disclosure agreement to study them) to protect them from looting by divers. Looting is a problem for wreck sites worldwide. The British cruiser HMS Exeter, which sank in the Java Sea in 1942 and was designated a war grave, has been stripped for scrap metal. In 2023, a forensic tagging system, pioneered by Historic England, was introduced to make tracking and recovering maritime artefacts easier.

However, Meyer-Kaiser’s research suggests that another activity could be causing much more damage: commercial fishing. At the Stellwagen sanctuary, every known wreck has been affected by fishing gear, which can weaken structures and make them less resilient to storms. In response, the sanctuary launched a pilot project called the Shipwreck Avoidance Program, and is working with fishing communities to enable maritime activities to continue while ensuring the preservation of the wrecks. ‘So far,’ says Meyer-Kaiser, ‘it seems to be working.’