Hundreds of coal mines could be converted into underground ‘gravity batteries’ to power the planet

By

Renewables are cheaper and more available than ever, but the green-energy revolution relies on our ability to store that energy. Wind and solar technologies can’t produce continuous power, so they can’t replace coal and gas plants unless we’re able to store the electricity that they produce for when the wind isn’t blowing or the sun shining. While batteries are an effective solution for daily energy storage, we still lack a cost-effective solution for storage over longer periods. But now, researchers at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) think they’ve found one in the form of old mine shafts. All that’s needed is 40 million tonnes of sand.

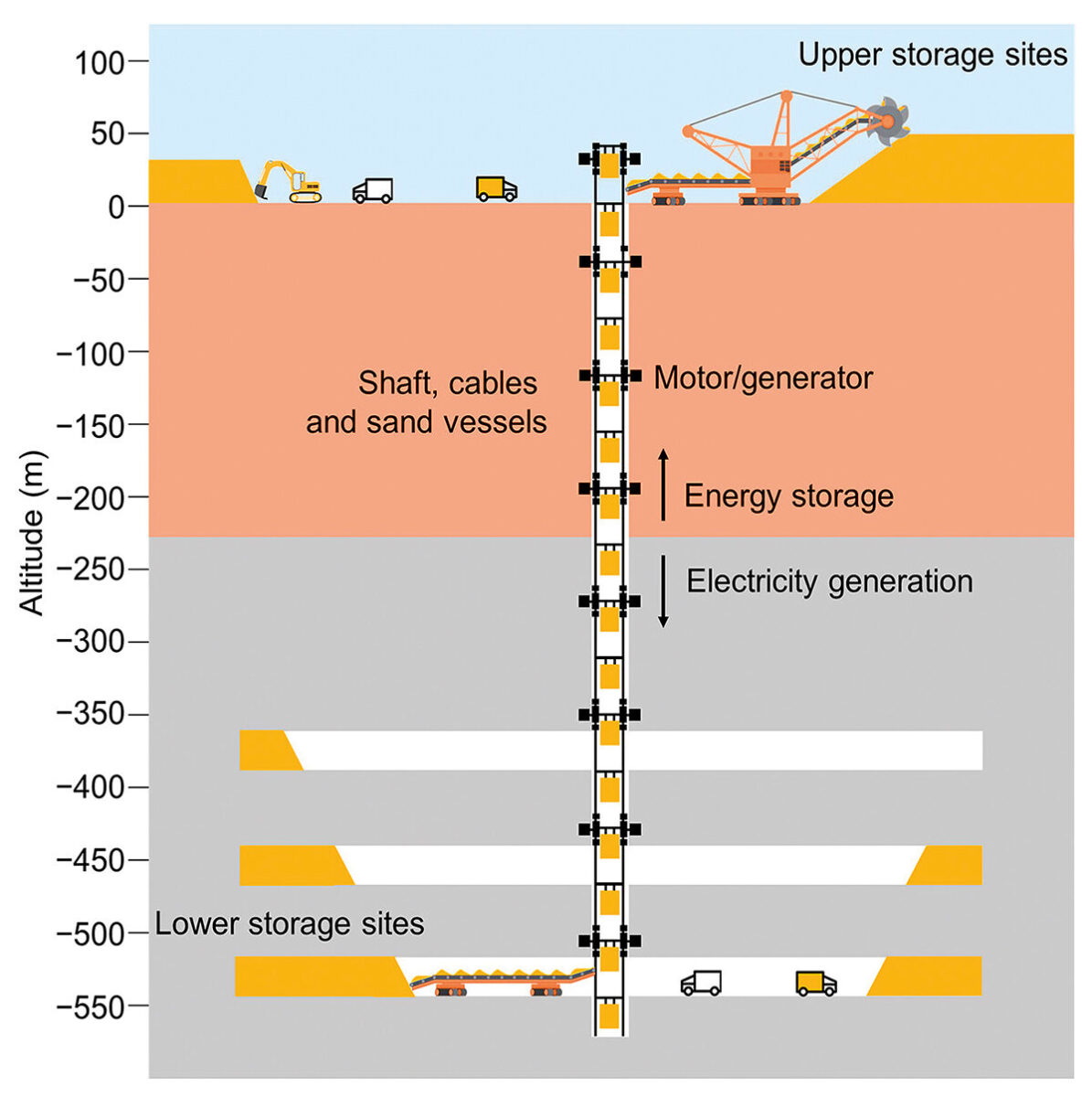

Julian Hunt, a senior researcher at IIASA and lead author of a new study that explores long-term energy solutions, explains that disused mine shafts can serve as energy-storing ‘gravity batteries’. The method, known as Underground Gravity Energy Storage (UGES), works by lowering containers full of sand into the mine. As the sand goes down, the motors that move it generate electricity via regenerative braking – a technique already used to recharge battery-powered cars by turning kinetic energy into chemical energy. The electricity can be produced when demand on the grid is high. When there’s excess energy in the grid, it can be used to raise the sand, storing the energy until it’s needed again.

Behnam Zakeri, who worked on the study, says that leading alternatives to gravity batteries, namely green hydrogen and pumped-storage hydropower, are limited by cost, efficiency and site suitability. Sand, on the other hand, is a clean, safe and readily available storage medium. ‘It doesn’t disappear, evaporate or self-discharge like batteries,’ says Zakeri. ‘It’s the perfect material for long-term storage – even more so than water, which comes with the risk of leakage and underground contamination.’

Between four and 40 million tonnes of desert sand would be needed per mine, depending on its size (desert sand has no use in construction and isn’t in short supply, unlike the sand found in lakes, riverbeds and on beaches, which is extracted at a rate of 50 billion tonnes a year). Using a project called the Global Coal Mine Tracker, which holds data on 3,760 coal mines worldwide, the researchers at IIASA estimate that UGES has the global potential to store as much as 70 terawatt hours of energy – enough to power the UK for three months.

While old mines would need to be retrofitted, many of the parts needed to store the sand – equipment such as conveyors and dump trucks – are already in place. Compared to other envisioned storage solutions, mines are also already connected to the grid and road infrastructure. ‘Using abandoned mines is much, much easier and cheaper than starting a new project,’ says Zakeri. Even after decommissioning, some mines require continued maintenance to ensure they don’t pose a risk to the environment and nearby communities. ‘It’s a redundant use of human resources and equipment, so let’s make better use of them.’

In fact, some energy-storage companies have already started to do just that. Scottish company Gravitricity has tested its own version of a gravity battery, which uses 25-tonne weights, and is now in the process of selecting a suitable mine shaft in Europe. Another firm, Energy Vault, has also developed a gravity battery –

one that uses a multi-armed crane to erect and deconstruct a tall tower composed of concrete blocks.

However, Zakeri says that UGES has an advantage over both in that it can store considerably more energy (up to 10,000 times more than Gravitricity), which also reduces its cost. ‘Keep in mind,’ he adds, ‘that while there isn’t a great need for long-term energy storage today, in ten or 20 years time, long-term energy storage will be crucial. UGES can be one solution to that.’