Rapid unplanned urban sprawl is accelerating a landslide beneath one of Central Africa’s most populous cities

By

For decades, the land beneath the eastern Congolese city of Bukavu has been moving, slowly sliding downhill. As the city has grown, the landslide has started to speed up.

The most destructive and deadly landslides can travel at speeds approaching several tens of metres per second, but many landslides move at a tiny fraction of that rate, sometimes as little as a few millimetres a year. While unlikely to claim lives, these deep-seated, slow-moving landslides do cause major damage to homes and infrastructure – although, on rare occasions, they have been known to fail suddenly, collapsing with little or no warning.

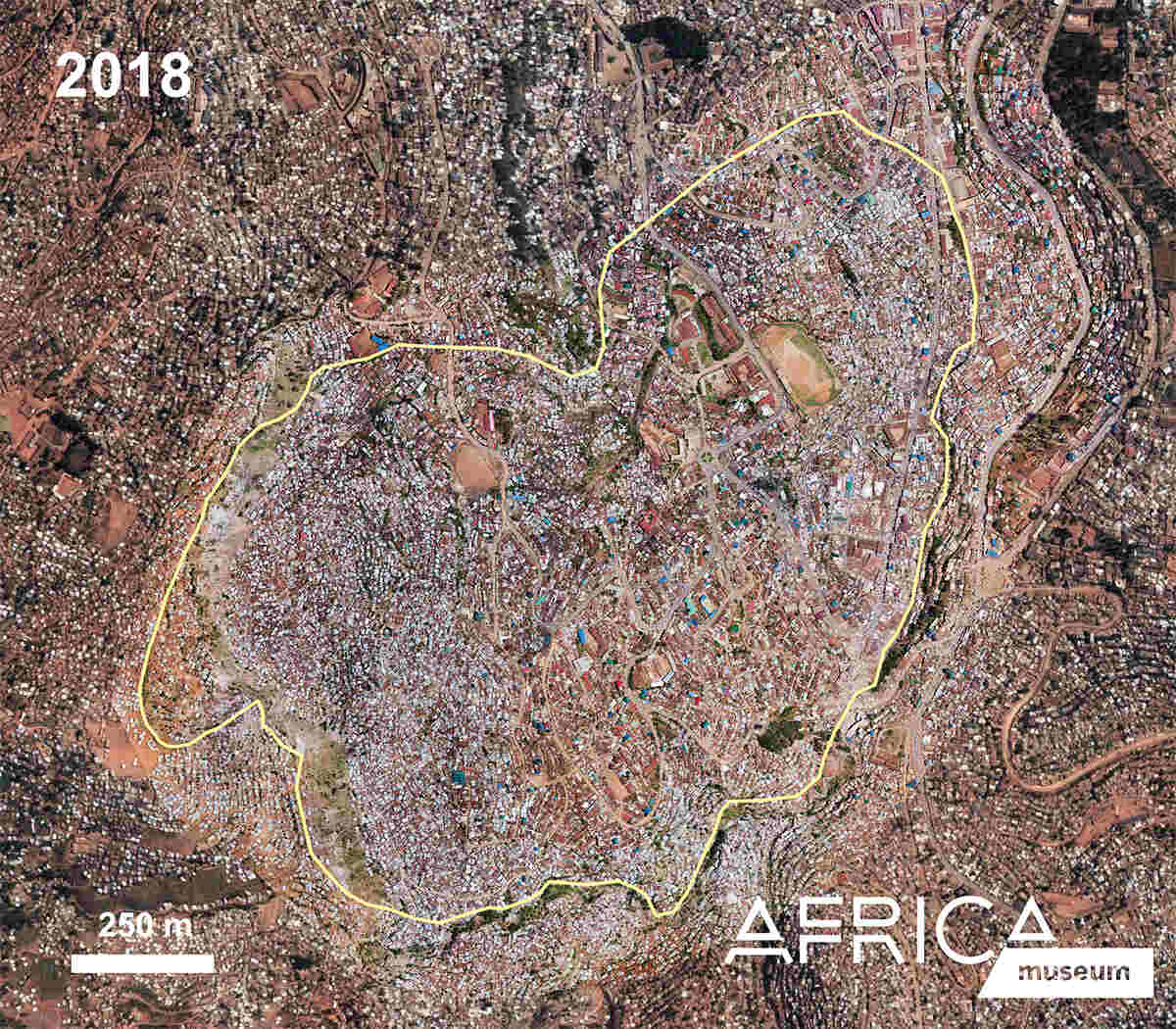

Roughly a third of Bukavu sits atop one of these deep-seated landslides. Some areas are dormant, but a significant portion of that land is continuously moving. One neighbourhood, Funu, is built entirely on a single slow-moving slide. Around 80,000 people live in this 1.6-square-kilometre area, where poor-quality, informal housing has built up over the years.

Since the 1980s, when Bukavu had just 168,000 inhabitants, the city has experienced a population boom. Most of this growth has happened from the ’90s onwards, as armed conflict and insecurity in the east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo spurred migration from rural areas to the city. Bordered to the north by Lake Kivu, along whose flat shoreline the city was first established, and to the east by Rwanda, the only place left to build was uphill.

According to the African Cities Research Consortium, Bukavu is built for a population of 300,000. It’s currently home to an estimated 1.2 million people. The rapid, dense and unplanned expansion of the city has had a direct impact on the natural creeping movement of the land, say researchers at Belgium’s Royal Museum for Central Africa, causing it to accelerate.

Little research has looked at how hillslope urbanisation might affect landslides in tropical regions, despite the rapid growth of many tropical cities. ‘Landslides are everywhere, but while you might find a few houses built on landslides in Europe or the USA, what you don’t find is part of a city built on a landslide,’ says Antoine Dille, a remote-sensing scientist at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. ‘This is something we typically find in low-or medium-income countries across Africa, Asia and South America. Yet most of our knowledge really comes from a handful of landslides in the Alps and the USA that have been studied for decades. The principle behind them is the same, but of course the environmental conditions are different.’

To understand how different climatic conditions (such as more-intense rainfall), types of rock, tectonic activity and, of course, urban landscapes might affect the Bukavu landslide, Dille and colleagues looked through hundreds of aerial images of the city. Heavy cloud cover in the tropics limits the use of satellite imagery, so the team turned to an emerging technology called synthetic aperture radar – remote sensors that can produce high-resolution landscape images in all weather conditions. Combining these techniques with GPS measurements and historical aerial images from the museum’s archives, they were able to form a complete picture of how both the city and the landslide have evolved.

It soon became apparent that while there were other environmental influences, most of the landslide’s acceleration was being driven by changes to surface and subsurface water flows – issues associated with roads, housing and storm drainage, as well as leaky underground infrastructure. In a 2022 review of water quality and pollution in Bukavu’s urban rivers, researchers at DRC’s Natural Sciences Research Centre describe the unmaintained, colonial-era sewer system as ‘entirely obstructed’. ‘The sewage network is nowhere near adequate for the amount of people who live there,’ agrees Dille. ‘There are huge leaks and broken pipes that have been around for ten years or so.’

Bukavu exemplifies many of the problems faced by cities experiencing rapid and informal growth. ‘It’s typically poorer people who settle on the slopes,’ says Dille. ‘People coming in from rural areas see that it’s close to the city centre, it’s safer than areas further out that are closer to areas with armed conflict, but it’s the most actively moving part of the city.’

More research will be needed to improve our understanding of how human activity influences landslides and how they can be mitigated. Dille says that working with communities to plant vegetation, install rainwater tanks or create better drainage systems would offer the simplest and most cost-effective solutions, but the fact that these neighbourhoods are mostly informal settlements makes it difficult to get such projects started because no-one is supposed to be living there at all. However, a pilot project in the Colombian city of Medellín has already shown that, while difficult, a reduction in landslide risk can be achieved when local government and vulnerable communities come together.