As the world turns away from fossil fuels, one question often overlooked is what to do with the thousands of ageing oil and gas platforms left vacant across the planet. When first built, little thought was given as to what to do with these hulks at the end of their productive lives. Only now, it seems, are major oil companies waking up to the reality that something needs to be done

By

Dossier

End of life disposal is rightly a high-profile issue, affecting everything from refrigerators to televisions. In the EU and other jurisdictions, dumping such items is illegal and manufacturers have had to work out how to recycle and reuse them. The same quandary applies to the rather larger items widely used by the offshore oil and gas industry.

The need to close down offshore oil and gas fields and break up their paraphernalia of rigs, platforms, pipelines, casings and fuel storage buoys has become extremely urgent. In the 50 years since the sector took off, thousands of structures built then and since are now nearer the grave than the cradle.

In the Asia-Pacific region alone, nearly 2,600 platforms, 35,000 wells, 7.5 million tonnes of steel and 55,000 kilometres of pipelines will need to be decommissioned over the next decade across a region ranging from India to Papua New Guinea and China to Australia. The potential cost for this could rise above £78billion. Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia are collectively thought to have around 1,500 structures and 7,000 oil fields that will be either 30 years old or require decommissioning by 2038. In the Gulf of Thailand, Chevron is faced with 300 platforms and 6,000 wells that must be decommissioned over the next decade. India has a further 300 structures and up to 1,000 oil fields facing the same scenario. Australia expects 40 offshore fields to cease operations over the next decade.

Closer to home, according to industry analysts Wood Mackenzie, up to half of the North Sea’s 600 installations – first installed 40 years ago – were due to be decommissioned by 2021. The UK government estimates the cost of removal at £20billion over the next 25 years in the North Sea. Globally, more than 4,000 such installations are scheduled for removal and 7,000 fields will cease production by 2022.

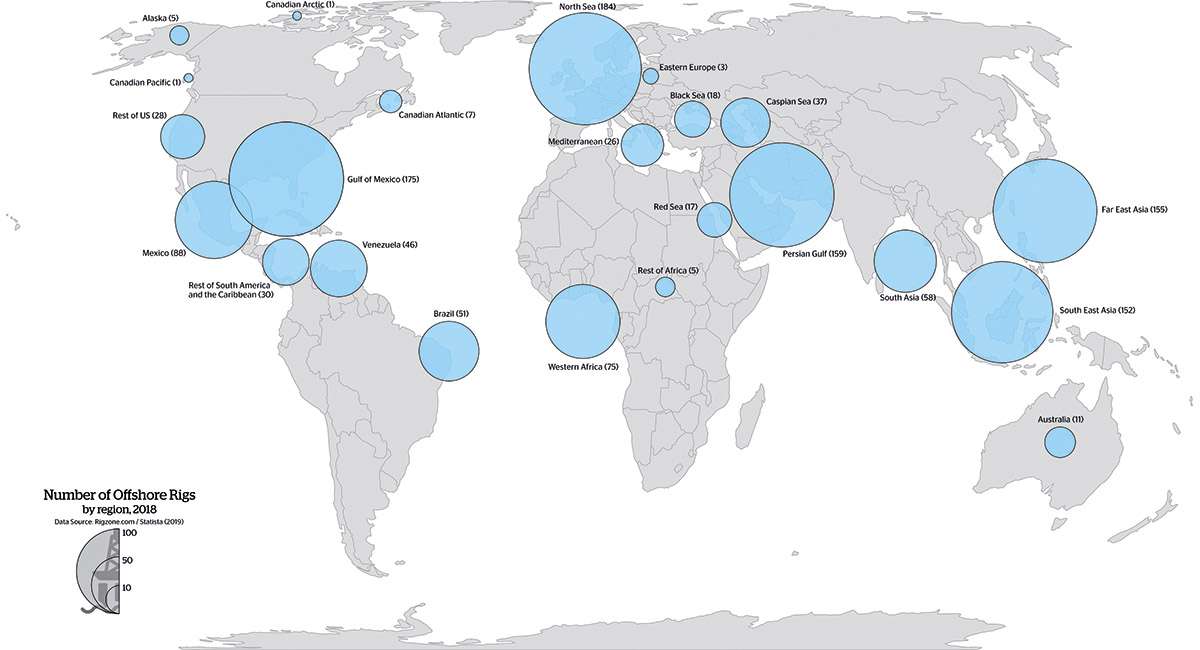

Global oil rigs

In a recent report Decommissioning – Will the Time Ever be Right?, Wood Mackenzie cautioned that ‘once thought of as a North Sea problem, decommissioning is quickly becoming one of the biggest issues in the global oil and gas industry’. It calculated that companies faced a decommissioning bill of £24billion between 2018 and 2022. Decommissioning in Asia was ‘a mammoth task’ and Wood Mackenzie warned that governments and companies faced ‘cost blowouts’.

While some areas, such as the Gulf of Mexico and the North Sea, have built up experience of dismantling oil and gas structures, the same cannot be said for the rest of the world. In the Asia-Pacific region, governments and energy companies face an unprecedented level of decommissioning for which, says Wood Mackenzie, it is under-prepared and lacks experience. Unclear regional government regulations coupled with a lack of local expertise mean that companies and regulators face a steep learning curve, high initial costs and the potential for mistakes.

The size of the problem

‘Globally the industry has been trying to avoid the subject,’ said Jean-Baptiste Berchoteau, upstream research analyst for Wood Mackenzie in Singapore, ‘but over the past two years we have started to see more activity, as operators realise the situation is getting a bit more critical. The magnitude and cost of work can no longer be ignored.’

‘Decommissioning has certainly been beneath the radar,’ adds Dr David Santillo, a senior scientist at Greenpeace Research Laboratories. ‘The information about just what is out there is part of the problem. In the North Sea and the Gulf of Mexico, we know what platforms are there and what stage of production they are at. But in many parts of the world, especially Southeast and East Asia it is hard to find out the total number of platforms, let alone when they started, what they drill for or where they are in their production cycle. There is a lack of transparency.’

How best to die

However, not everyone agrees with this picture. Surprisingly, given the fact that its members would gain from a surge in demand for decommissioning, this includes the International Marine Contractors Association (IMCA). Allen Leatt, the IMCA’s CEO, thinks that we will have to wait a while yet for the age of decommissioning to arrive. ‘I don’t think we are there yet. Decommissioning has been around for the last 20 years but it has been lumpy. The major companies may move out [from a field] but smaller ones, focussed on smaller investments that come from late-life field extensions, come in. The market can be much more dynamic than you think.’

Nevertheless, in a sign of the urgency with which the issue is now viewed, the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers (IOGP) updated two advisory papers on decommissioning last year and chaired its first meeting on decommissioning in Asia in Kuala Lumpur. Discussions focussed on greater engagement with local governments but did not address secondary issues, such as recycling of scrap metal. ‘We’re actively reaching out to members to speed up learning and bring good practice on decommissioning to support safe and responsible decommissioning,’ said Wendy Brown, environment director at the IOGP.

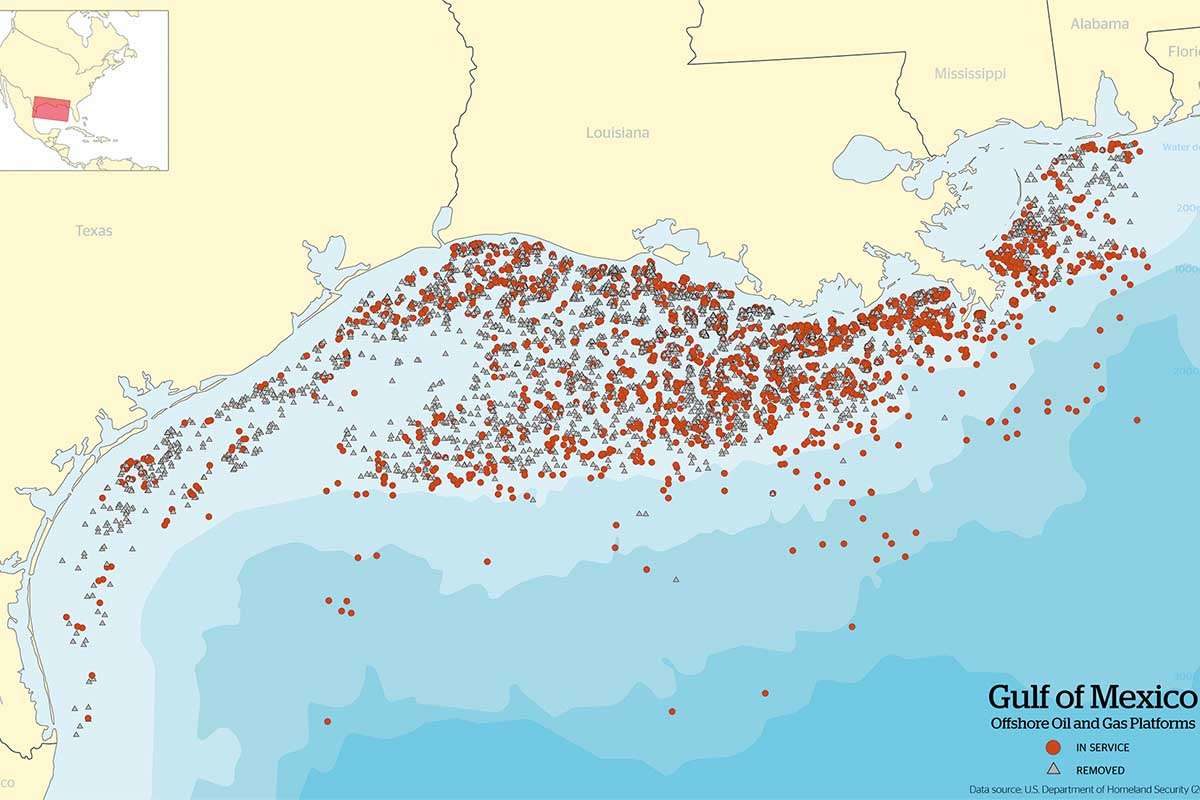

Offshore rigs in the Gulf of Mexico

For most onlookers the immediate concern is pollution related to decommissioning activities. The well plug phase is considered the riskiest and Berchoteau notes that ‘live hydrocarbons are involved and there is poor availability of data on well conditions’. However, the major risks have less to do with spectacular oil spillages, such as the BP Deepwater Horizon spill in 2010, when 4.9 billion barrels of oil were discharged into the Gulf of Mexico while a deep exploratory well was being drilled. Instead, they are more aligned with long-term pollution. ‘Chemicals can leak out from the structure and from drill cutting – they can be fairly toxic materials,’ says Dr Lyndsey Dodds, head of marine policy for WWF-UK.

While most companies have experience of plugging wells, the challenge is that a single platform can support lots of wells. ‘You are cutting large metal structures, there are safety issues for both humans and the environment,’ says Santillo.

Essentially, options for decommissioning are determined by circumstances such as the age of the rigs and the depth of the seabed. The wells are plugged and capped with concrete in a process known as ‘plug and abandon’. Associated platforms, jackets, topsides and pipelines are then cleaned, dismantled in situ or towed to shore for their scrap metal to be recycled.

Current thinking identifies three ways in which rigs can be dismantled: single lift operations, which are generally practical for smaller installations; reverse installation, where a rig erected in modular form is dismantled the same way; and the piecemeal approach, whereby a set of excavators and a demolition team dismantles the rig piece by piece. As well as requiring vast marine vessels (see Heavy Lifters), other tools needed include abrasive water-jets (which use high pressure water and gritty materials) and diamond wire cutters.

When it comes to best practice, the complexity, as Dodds at WWF says, is such that ‘it should be done on a case by case basis’. Elderly assets often shift from operator to operator, modifications may not be recorded and technical information can be poor or out of date.

Duncan Manning, assets and decommissioning manager for Shell’s Brent platforms in the North Sea, acknowledges that his company has learnt lessons since the 1995 Brent Spa fiasco, when it sought to dump a redundant oil platform on the Atlantic seabed. Four platforms are being dismantled in a process that started 11 years ago and which will only finish in 2020. Shell has consulted with 180 stakeholders, from fishermen to local communities, environmental NGOs and academics. ‘The regulations have changed [since 1995],’ he says. ‘We’ve worked hard to understand their concerns. I’ve personally travelled the length and breadth of the country to hear their views and put our perspective across.’

Brent Spar

What do you do if you have a huge oil platform which you no longer need? In 1995, Shell’s answer was to tow its Brent Spar platform, which operated as an oil storage and tanker loading buoy, 160 miles west of Scotland and dump it, allowing it to drop 1.6 miles to the seabed. Extraordinarily, the UK government of the day gave the green light to the proposal, a decision that sparked environmental protest, led by Greenpeace. Direct action included occupation of the structure for three weeks, a high-profile boycott of Shell service stations in Europe (at least one station was subjected to an arson attack). Shell backed down, towed the platform to a Norwegian fjord and later dismantled Brent Spar and used much of the metal in new harbour facilities near Stavanger.

‘Brent Spar was just a small component of hundreds of pipelines,’ says Santillo. ‘The cumulative impact was the concern. You end up changing the chemical and physical environment of the seabed over a much wider area.’ As the wider Brent field is dismantled, Greenpeace is concerned that the same issues are arising, though Shell’s Manning emphatically denies that this is the case.

Scrap heap challenge

An overlooked issue is that oil platforms can be a haven for marine wildlife. According to the Coastal Marine Institute, a typical eight-legged structure provides a home for 14,000 fish. A 2014 study by the University of California found that California’s 27 oil platforms are among the world’s most productive marine fish habitats. Juvenile rockfish, species of which are over-fished, have been found to live in higher densities at several of the platforms as compared to nearby natural reefs.

In the Gulf of Mexico, a policy known as ‘rigs-to-reef’ provides an alternative to complete rig removal in which an oil company chooses to modify a platform so that it can continue to support marine life as an artificial reef. The oil well is capped and the upper 85 feet of the platform is towed, toppled in place, or removed. More than 530 rigs have been ‘reefed’. California, however, has not approved the practice.

Even where a rig-to-reef policy is deployed, the question remains as to exactly where the dismembered structures and scrap metal – including 55,000 kilometres of pipelines in Asia-Pacific alone – will end up. The prospect of an oil rig graveyard, similar to the ship-breaking beaches of Chittagong in Bangladesh (known as the world’s graveyard for the global merchant shipping fleet, where tankers and cruise liners go to die) and through which shipowners often seek to absolve themselves of environmental and human rights responsibilities, strikes most observers as appalling.

‘The idea of just shipping structures to the country with the lowest regulatory standards is sickening – I think the companies involved in decommissioning are very aware of the reputational risk and they won’t take it lightly,’ says David Beckstead, a Thailand-based consultant for lawyers Tilleke & Gibbins.

The IOGP describes towing dismantled rigs to be scrapped in Bangladesh as ‘completely unsafe and unacceptable’. However, the IOGP admits to uncertainty over onshore recycling and no centres in Asia have been identified. Dockyards in China that specialise in clean scrapping of container ships are a possible backstop option and a Thai scrapyard has so far handled five jackets (the lower, structural sections of a platform) and topsides. The Australian oil and gas industry is considering a decommissioning hub in Perth to handle metal from Oceania, Papua New Guinea, New Zealand and parts of Indonesia.

Leatt, though, is happy for the market and local players to pick up such work and is confident that local regulations will suffice. ‘If you are in West Africa, where are you going to take [your platform]? You’re not going to take it to Europe. The industry is always under pressure to increase local production. Construction facilities are increasingly local so I imagine end of life facilities will be as well. As each market develops, the supply side will react to support that.’

You might like

‘At the moment the challenge is that it [the regional rig scrapping industry] is small scale,’ said Berchoteau. ‘But the industry has anticipated this and we do expect to see more yards becoming established in Thailand and Indonesia.’

Dr Santillo is emphatic that the oil and gas industry should not follow the lead of the shipping industry. ‘We must not repeat those mistakes,’ he says. ‘The technology is there for companies to deal with rigs from cradle to grave. From a financial point of view these things are a long-term liability if they are not decommissioned properly. This is not something a forward-looking company would want to have on their books or to pass on in a questionable way. They need to do the responsible thing about their long-term legacy.’

Rigs to reefs

Many oil rigs have nurtured cold-water coral systems and act as small offshore islands, supporting marine communities and attracting fish and birds. ‘Marine life is attracted to complex structures that rise vertically, which is exactly what these vast rigs do,’ says Emily Callahan, co-founder of Blue Latitudes, a California-based marine environmental consulting firm. Some rigs that have been reefed support large populations of endangered species such as red snappers. ‘Near-shore species are affected by development, run-off and erosion and they seem to find these reefed rigs, which are often miles offshore, a much better habitat,’ says Callahan.

Reefing a rig is also attractive to oil companies as overheads are generally 50 per cent lower than removing the entire structure, though contracts require companies to pass 60 per cent of their cost savings to the state for marine protection. Outside the US, just two rigs have been reefed, one in Malaysia and one in Brunei. But Callahan believes that rigs-to-reef programmes could be operated across the world. Environmentalists, however, are less sure. ‘We are cautious, it needs to be addressed on a case by case basis,’ says WWF’s Dodds. ‘It’s unlikely to be an ideal solution. No kind of artificial reef can ever be as beautiful as the natural marine environment.’

Overseeing the clean-up

There is, however, one overarching problem: when it comes to adopting a worldwide consensus on decommissioning there is no global, legally-binding treaty dedicated to the safe and environmentally responsible disassembling of rigs and other structures. The one shining light is the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR), a treaty under which 15 governments and the EU cooperate. OSPAR demands that offshore structures be completely removed from their marine sites and brought to shore for re-use, recycling or other disposal. ‘I wouldn’t say all the energy companies are always doing the right thing but this process is supported by Greenpeace and the oil and gas companies,’ says Santillo, ‘It is pragmatic and has led to better designs, better development of systems for recovering materials – there has been a lot of environmental benefit.’

OSPAR does provide exemptions to leave a structure in place if it is physically impossible or environmentally dangerous to move them. ‘You have some big, complex gravity-based structures that are incredibly difficult, sometimes impossible to remove,’ says Santillo. ‘They can sink ten metres into the seabed. Removing them can potentially create more pollution rather than less.’

Manning says that just 11 of the 470 oil and gas structures in UK waters may face this scenario and points out that Shell ‘retains liability for them in perpetuity’.

£120,000

The sum above was paid by Transocean to local communities by way of apology for what it called ‘disruption’ after one of its oil rigs broke loose from a tug and became grounded on Dalmore beach in the Outer Hebrides in 2016. The 17,000-tonne structure, Transocean Winner, came ashore at Lewis after becoming detached during a storm in August. Despite the rig carrying 280 tonnes of diesel, stored within four tanks, two of which were damaged, little environmental pollution was caused – 12,000 gallons of diesel oil leaked from the rig but was mostly dispersed by the rough seas. More than 15,000 tonnes of debris was collected from the site and it took three weeks before the rig could be refloated and subsequently towed to Turkey. A report by the Marine Accident Investigation Branch highlighted the lack of a contingency plan for stormy weather and also found the tow line was in a poor condition.

Dodds believes the emphasis OSPAR places on the oil and gas industry coming up with hard data is crucial. ‘The burden of proof is with the companies to show that there would be no damage caused by leaving these things in situ. They can’t just assume everything will be OK.’

The only other international regulation with tangential influence on decommissioning is the International Maritime Organisation’s edict relating to the safety of navigation. This insists that any structure must be cut to a certain depth below sea level, usually around 85 feet.

Elsewhere, the level of regional regulation varies enormously. As the IOGP euphemistically puts it: ‘Some country [regulatory] regimes are in various stages of development and maturity.’

The closest Asian regional equivalent to OSPAR is the ASEAN Council on Petroleum (ASCOPE), which issued decommissioning guidelines in 2015. This balanced what ASCOPE described as ‘environmental protection, cost, safety and technical considerations’.

In Thailand, the National Petroleum Act establishes the legal foundation for decommissioning while the government has also issued guidance; Thai law also allows NGOs to take legal action directly against individual companies. In Indonesia, however, frameworks are much weaker and undermined by the lack of security and clean-up provisions in energy contracts. According to Berchoteau, China has similarly weak regulations. ‘A regional body can issue guidelines but when it comes to regulatory teeth that has to come at the national ministerial level,’ he added.

Leatt, however, is more sanguine, saying that ‘every country has its own regulations and their authorities certainly have teeth’. He adds: ‘We don’t have a global body for constructing these platforms so it’s difficult to imagine an overarching one for decommissioning.’

The Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea remains an area hotly contested by its five littoral who are keen to further exploit its fossil fuel reserves, Exploitation, however, began more than 50 years ago and, as new companies have come in, they have faced the onerous task of taking out old Soviet infrastructure, pipelines and well heads, and generally clear up the mess. In the past five years, Dragon Oil, an Azeri company, has plugged several dozen wells there. The Caspian may not experience the mountainous seas and Force 12 gales that tear across the North Sea, but it can still present challenges for decommissioning work. This means that what might be the best environmental option for the North Sea, might not be suitable for the Caspian.

One challenge peculiar to the Caspian is that platforms need to be dismantled by vessels and equipment in situ. The Volga is the largest of 130 rivers to flow into the Caspian, but none is big enough to be navigated from point to point by the world’s largest lifting equipment and vessels typically used for decommissioning. Only the vessels already in there can do the work. It was once suggested that decommissioning companies cut a large crane vessel into several pieces to get it through the canals and reassemble it in the Caspian – unsurprisingly, they declined. Since it will be expensive to ship material out, the favoured options are to use local labour and where possible apply reverse installation and then remove, recycle and re-use. The Caspian also faces pressures from agricultural and industrial activity in the surrounding land masses. The valuable caviar industry of the northern Caspian may militate against the option of simply cleaning the rigs and leaving them as wrecks.

The burden of proof

Another opaque area is that of where responsibility lies for removing rigs, capping wells and meeting the sizeable price tag. Large structures can cost hundreds of millions of pounds to be dismantled; at the bottom end, the small sub-sea wells may cost £1m-£2m. In between there are structures that might come in at £10m.

In many cases, the licences drawn up between energy companies and governments require the state to bear the costs and responsibility. ‘You just couldn’t imagine this happening on land, offshore companies get away with so much more,’ says Santillo. The UK government agreed to subsidise the cost of decommissioning in the North Sea, something which cynics suggest is why the oil and gas industry is so supportive of OSPAR.

‘The contentious issues lie around liabilities and regulation. That’s been something no-one really wants to tackle,’ says Berchoteau. ‘Contracts in Indonesia didn’t have any clauses on decommissioning, so does that go back to the government or the operator, can that be done retroactively? It’s not black and white, everybody is going to have to take some share of the responsibility.’

The only other global regulation in the picture is the ‘London Protocol’ (also known as the London Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter), originally established to cover how materials can be dumped at sea. Over time, the protocol has tightened its regulation to the point where issuing permits for dumping, managed or not, is no longer the default option when it comes to getting rid of structures. ‘The protocol now has a much greater emphasis on dismantling structures and reusing their material, that is now the first option,’ says Santillo.

Companies face the temptation, he says, of wriggling out of clean ups on the grounds of insurmountable technical challenges. ‘We are often told by companies that their concrete structures are already clean but that is often far from being the case. You get a lot of muck inside them.

Heavy lifters

Just how do you get an oversized piece of metal out of the water, often in high seas? The approach to dealing with a defunct platform varies and is largely determined by the depth of water in which it stands. Those structures in deep water will by necessity be floating, so are towed to shallow water or yards where they can be recycled or refitted; in mid-water depths, platforms can be large and heavy and will require heavy-lifting machinery; shallow water platforms will usually be dismantled in situ. Whether or not the prevailing local climate is harsh or benign also influences the approach of contractors.

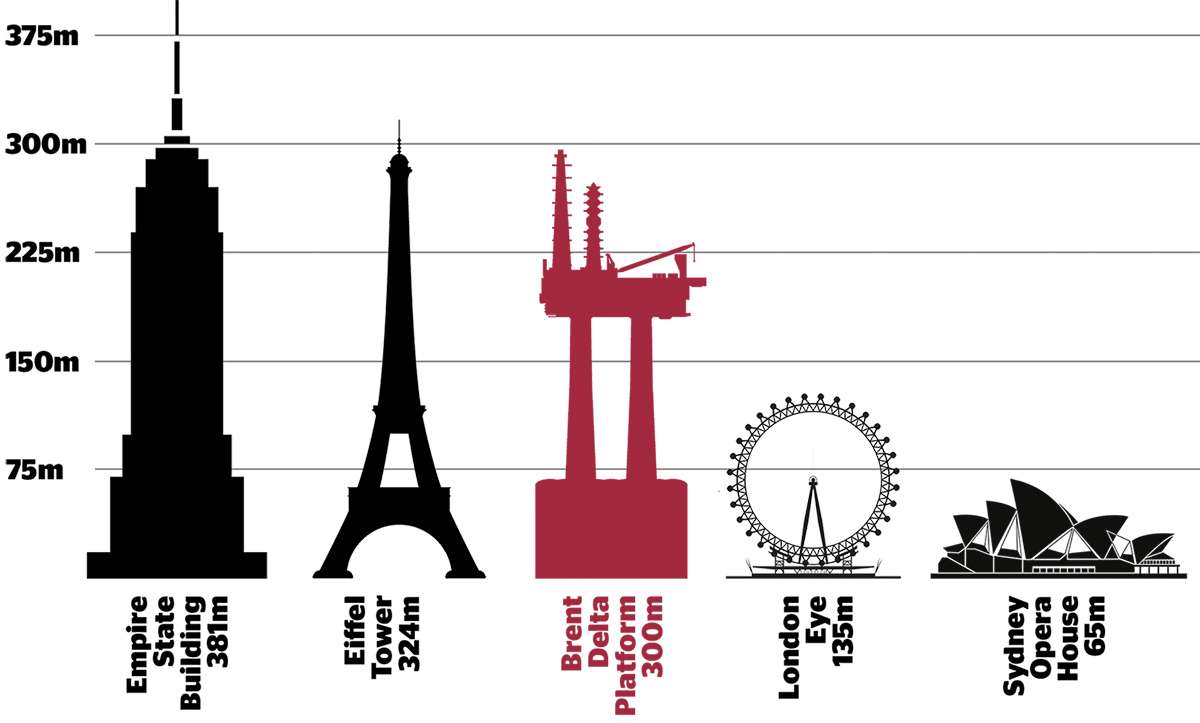

The machinery ranges from small crane barges with revolving lift capacities to the record-breaking installation/decommissioning and pipelay vessel Pioneering Spirit, which can remove the entire topside of an offshore platform in a single lift. In the latter case, the actual lifting process takes only a few seconds. Often described as the world’s largest ship at 382 metres in length and belonging to Allseas, Pioneering Spirit is unique. It lifted the 24,200 tonne, 44-metre-tall Shell Brent Delta topside and delivered it to a northeast England disposal yard in April 2017.

‘It’s not beyond the wit of these companies to come up with solutions. They can drill round corners, drill through several layers of complex shales. If they can’t drill through six inches of concrete to clean up these structures and dispose of them properly then it suggests they haven’t invested in doing so.’

The WWF is also concerned that some companies try to water down their requirements to remove structures. ‘We see them come up with excuses for leaving things, arguing that the technology is not available to move or clean up,’ says Dodds. ‘We wonder if they would have found a way [to overcome decommissioning problems] if they were to make money from it.’

An obvious question is: why on Earth did no-one assume, back in the 1970s, that such platforms would one day have to be dismantled and build that into costs and design? ‘Attitudes of governments were more laissez-faire, the priority was to access the oil and gas,’ says Santillo. ‘Offshore industries have certainly been given an easier ride in terms of operating standards.’

This lack of planning was likened by Shell’s Manning to cars being built without seatbelts, which became common practice later on. ‘You have to remember there was an energy crisis, the focus was on getting energy out of the ground, tempo was important,’ he says. Since the mid-1990s, all offshore structures must now be built with decommissioning in mind.

Manning is confident that major companies will be mindful of their reputation, even when they operate in regions beyond the reach of OSPAR. ‘With modern communications, news travels fast and poor practice in one part of the world will soon become known. They will want to be seen as responsible global operators.’

While the oil and gas companies prevaricate, others may have to play increasingly influential roles. ‘We really need the public, environmental activists and shareholders to be engaged to ensure we get that transparency,’ says Santillo. ‘There will be mishaps along the way but if the rules that exist in the northeast Atlantic stay in place or are tightened things could run smoothly. But I’m not confident yet that the checks and balances will kick in.’