With weakening efficiency and significant ecological impact, it’s time to reconsider dams as a crucial source of renewable energy

By Victoria Heath

The significant damage caused to a major dam in southern Ukraine on Tuesday highlights the great impact that can be caused by these large structures. When damaged, they can unleash huge surges of water, leading to flooding, emergency evacuations and endangering the lives of civilians.

But even when operating normally, dams have been proven to worsen climate change and cause a plethora of issues for the planet and environment. So, the question is: are dams still a necessary source of modern-day renewable energy?

The purpose of dams

Dams are used to control flooding and store water in reservoirs, as well as to generate power. The number and size of dams soared in the 20th century and into the 21st. There are now more than 57,000 large dams worldwide – ‘large’ defined as higher than a four-storey building (15 metres).

The water that is held in these reservoirs can help to generate hydroelectric power for power stations. Using the energy from falling water, water turbines can be powered which can then drive electric generators.

For example, the 30-metre-tall Kakhovka dam in Ukraine, holding a reservoir containing an estimated 18 cubic kilometres of water, supports the power of the Kakhovka hydroelectric plant.

The weakening efficiency of dams

Nearly 20% of the world’s electricity is generated through dams’ production of hydropower. Yet, climate change has caused the power that dams can generate to plummet. On all five continents, droughts have led to reservoirs dropping below levels required for the maintenance of hydroelectric production.

Hoover Dam, which holds the U.S.’s largest reservoir, has faced a 25% decrease in its hydropower capacity, while the largest manmade reservoir at the Kariba Dam on the Zambia-Zimbabwe border fell to 11% of its capacity by 2019.

Dams also take an incredibly long time to build, averaging more than eight years to construct. New dams that are produced must be expanded to accommodate the increase in floods due to climate change, although this capacity will go mostly unused and contribute to the inefficiency of dams. Once completed, they are less valuable in the fight against climate change than infrastructure which can operate much more quickly.

In 2014, an Oxford University study of 245 dams found that they were cost-ineffective, with actual costs nearly double compared to their budget. A follow-up study in 2021 found a consistent bias in cost-benefit analyses of public investments, which leads to an overestimation of the benefit of a project, and an underestimation of costs. Out of eight investment types (including roads, bridges and railroads), the overrun in costs for dams was the highest.

The ecological impact of dams

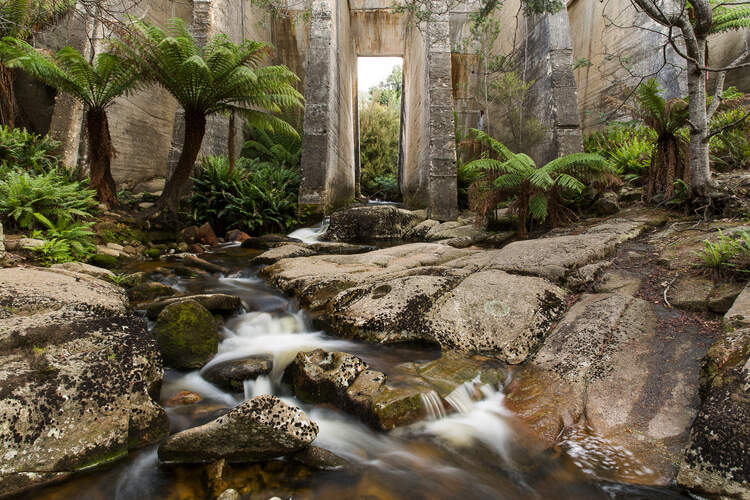

The large-scale construction of dams is described as the biggest single alteration of the freshwater cycle in the Anthropocene. Dams have ravaged the ecosystems of at least two-thirds of the world’s major rivers, and collectively flooded an area bigger than the United Kingdom.

Ecologists have also noted that local fish populations can be harmed due to the way that dams change the function of rivers.

‘Most dams don’t simply draw a line in the water; they eliminate habitat in their reservoirs and in the river below,’ says the Hydropower Reform Coalition (HRC).

Organic materials which would usually wash downstream instead collect behind dams, causing a buildup of oxygen. This can trigger algae bloom, leading to oxygen-starved ‘dead zones’ which are no longer able to support any life in the river. The inability for solid materials to pass downstream causes the land to become less fertile, and riverbeds to become deeper or entirely erode away.

‘Rivers carry sediment that feeds the fish, it feeds the entire vegetation along the river,” says Professor of Geography and Environment at Michigan State University, Emilio Moran. ‘So, when you stop sediment flowing freely down the streams, you have a dead river.’

Other animals, not just marine life, are affected by the production of dams. If a planned hydroelectric project in Sumatra, Indonesia is completed, the Earth’s rarest ape, the Tapanuli orangutan, could be made extinct.

In Brazil, more than 200 hydroelectric dams have been proposed which can help meet growing energy demands in the country. However, the dams would flood more than 10 million hectares (25 million acres) of the Amazon rainforest.

There are also concerns that installing many dams in a geologically unstable region or area with large faults, such as southern Anatolia in Turkey, may increase its risk of earthquakes.

‘Turkey has more than 600 dams, which is a huge number, and there is a project to build 22 more in the southern Anatolia region,’ says Egyptian dams expert, and Professor of Geology at Cairo University, Abbas Sharaki.

Without conducting in-depth studies, it is difficult to conclusively determine the role of dams in earthquake events. But Shakari notes that due to the geological nature of the region, it is a ‘dangerous matter’ that the water storage has ‘reach[ed] 120 billion cubic meters.’

The future of dams

Some countries, such as the USA, are in the process of decommissioning dams entirely. In 2022 alone, 65 dams were removed, allowing 430 upstream river miles to reconnect across 20 states. And since 1912, at least 2025 dams have been removed in the country.

This year, the largest-ever river and salmon restoration project will begin in the Klamath River in the states of California and Oregon. After decades of advocacy from the Karuk, Yurok, Klamath and other tribes, the project aims to restore salmon runs, improve the quality of water and support the revitalisation of food sovereignty and cultural connections.

“The Klamath salmon are coming home,’ Chairman of the Yurok tribe, Joseph James said. “The people have earned this victory and with it, we carry on our sacred duty to the fish that have sustained our people since the beginning of time.’

The WWF has also released ten concepts to consider in the planning, developing and operating of dams. These include ensuring dams are adaptable in response to climate change, allowing for flexible operation over a long-term period and ensuring planning processes include meaningful contributions from affected communities and representatives of different economic sectors.

After the 2021 World Hydropower Congress, the ‘San José Declaration on Sustainable Hydropower’ document was announced, detailing the industry’s commitments, such as consulting communities threatened by dam construction, managing biodiversity impacts and banning projects in UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

‘The holistic view in the long run, I think, is one that will allow for a greater ability of the [freshwater] system to be resilient in the face of a changing climate’, says WWF’s lead freshwater conservation scientist, Michele Thieme.

‘In practice, we will have some parts of our rivers that are more working rivers and some parts we keep free flowing. That’s the ideal because, to survive and to flourish we also need to use water in ways that are sustainable,’ Thieme continues.