As much as 70% of the world’s internet traffic flows through a band of rural counties I’m the American northeast

In the southwestern outskirts of Washington DC, the capital’s residential suburbs slowly give way to historic towns, a protected Civil War battlefield, rolling hills and the green pastures of Northern Virginia. For residents, however, the sounds of the countryside are interrupted by a constant hum – the noise of thousands of cooling systems that keep the internet’s traffic flowing.

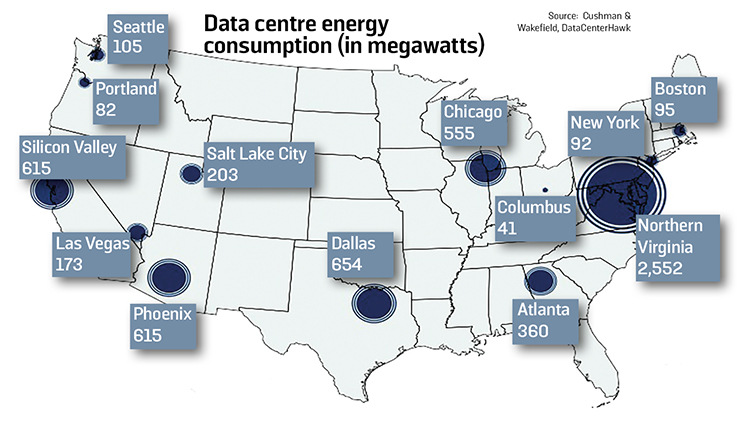

Various sources, from Greenpeace to the Washington Post, claim that anywhere between a third and 70 per cent of the world’s internet traffic flows through a handful of rural counties in the American northeast. While these figures are difficult to verify, the region is host to the largest concentration of data centres in the world. Large, windowless, warehouse-like data centres that house the high-speed computers needed for our growing reliance on 5G and AI technologies rise up amid the traditional farm buildings.

Across the globe, in major cities such as London and Beijing, there has been a recent explosion in the number of new data centres being built, but nowhere more so than in Northern Virginia – which has been dubbed ‘Data Centre Alley’. Julie Bolthouse, director of land use at the Piedmont Environmental Council, says that there are a number of reasons why. At first, it was the close proximity to federal government services and the availability of affordable land. Over time, and with the development of Amazon’s seven-building data centre in 2006, all the services needed to build and run a data centre – from construction services to maintenance staff to emergency generators to security personnel – were within easy reach of anyone wanting to build a new one. ‘Now everybody wants to be in the biggest data centre market in the world,’ says Bolthouse. ‘And that means everybody wants to be here.’

Not everyone is happy about that. Residents have complained about the noise and the visual blight of huge warehouses. Some fear data centres will depress property prices. The Piedmont Environmental Council, an environmental organisation in Virginia, worries about the immense energy consumption of these facilities and the strain they put on the power grid. ‘We have a utility company that can offer endless amounts of power, and I say endless because it will always build more infrastructure,’ says Bolthouse. ‘One of our big concerns is that residents are subsidising this industry; we’re helping to pay for all the new infrastructure.’

In addition to energy, concerns have been raised about the vast amount of water needed for cooling systems. ‘In Loudoun county,’ says Bolthouse, ‘potable water usage has increased by about 270 per cent as a result of data centres.’ In some parts of the state, data centres are relying on groundwater extraction for cooling. ‘And that also is very concerning, because no-one’s really paying attention to how much is being withdrawn.’

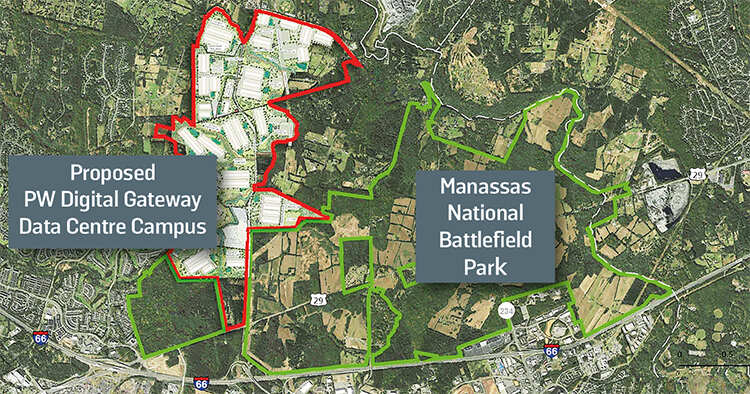

One particularly contentious project is the Prince William Digital Gateway. This massive data complex, planned for an area adjacent to the Manassas National Battlefield Park, would sprawl across two square kilometres – an area roughly the size of five Pentagons, adds Piedmont Environmental Council’s president Chris Miller. Proponents tout the economic benefits, including tax revenue and job creation. But critics, which include the council as well as the American Battlefield Trust and local residents, are worried about the environmental costs. ‘Imagine building a structure of that size next to Hampstead Heath,’ says Miller. ‘It’s that level of industrial impact on a national park that’s so staggering.’

Bolthouse explains that local governments in Virginia are ‘very accommodating’ to the expanding data centre industry. As a result, there are no government data on the number of existing data centres in Northern Virginia, the number of new applications, or the amount of resources they will use. ‘We’re the only ones who are even attempting to map what’s out there,’ she says. ‘Our locality should not be able to approve something like the Digital Gateway in one fell swoop without any type of state oversight.’

As data centres continue to expand around cities across the world, Bolthouse says that the USA represents the canary in the coal mine. ‘You can look to see what we’ve done, and see what could happen in the UK.’