Andrew Brooks looks at how consumer boycotts and celebrity activism reflect our changing, complex times around the world

Today’s cinema listings are dominated by sequels, prequels and comic book movies. Every second new movie is a reimagining of an established story. It feels like filmmakers have lost their creative vision and nothing novel is being projected on the screens. Yet, some of the greatest films ever made have been part of established series.

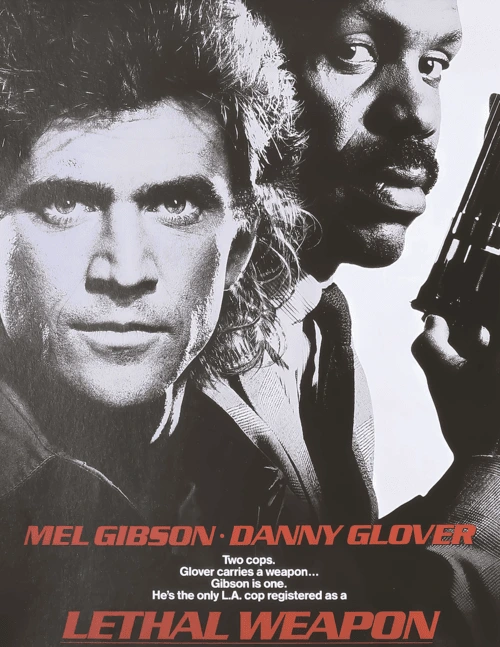

The year 1989 was a high-water mark in the history of the action movie. Opening the summer blockbuster season in May was one of the all-time greats: Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (a sequel). Then Tim Burton’s Batman (a comic book movie) hit US cinema screens in June and went on to be the highest-grossing film of the year. The summer season was rounded off by the release of the third most successful movie of the year: Lethal Weapon 2.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

The second instalment in the Lethal Weapon franchise may not be as fondly regarded as the year’s other two action-adventure classics, but in its own way, this police procedural is worth remembering as it is powerfully intercut with seismic shifts in geopolitics.

The plot centres on the relationship between two mismatched detectives, Mel Gibson’s Martin Riggs, an erratic and high-octane white cop, and Roger Murtaugh, the solid and dependable Black family man, played by Danny Glover.

As a biracial pairing that cast the Black man as the organised rule-follower, their double act was still a novelty in the late ’80s, and their enduring friendship gave social texture to the film series. Like his character, Danny Glover was always more thoughtful than his more famous, eccentric and now morally compromised co-star.

Glover played a key role behind the cameras in directing the politics of the project. The bad guys in the plot are white South African drug smugglers with diplomatic status who are bringing narcotics and illegal shipments of gold into California.

The subtext is barely concealed: America shouldn’t be trading with the evil state and shrouding it in respectability.

The denouement is a scene in the Port of Los Angeles. Riggs and Murtaugh have discovered the drugs and, following a shoot-out that leaves Riggs wounded, Murtaugh, lying on the dockside, aims his gun at the Afrikaner leader, Arjen Rudd, who is high above on a ship about to escape. Rudd’s gun is empty, but he holds up his passport, like a tiny leather-bound shield and claims ‘diplomatic immunity’. Glover’s character fires, kills him, and declares it has ‘just been revoked’.

A clear message from Hollywood: the South African state is illegitimate and the USA should sever all associations. Lethal Weapon 2 was advocating for a boycott of South Africa.

Throughout the 1980s, the USA was still open for business with the pariah apartheid regime, and the government in Pretoria was granted legitimacy and tacit support as it offered both an important economic partner and a bulwark against the feared spread of Communism. Despite the US government’s backing for its Cold War ally, boycotts were commonplace, particularly among African Americans.

Under pressure from the Black community, hundreds of American banks, businesses and universities withdrew from South Africa. Despite federal-level recognition, many local governments severed ties. US athletes and artists, including Tony Bennett and Muhammad Ali, refused to appear in South Africa. This was a tumultuous moment in global affairs: the Berlin Wall fell, the Soviet Union began to break up, the Cold War ended and liberal economic and democratic values spread across Africa and Asia.

Following shortly after these world-shaking geopolitical shifts, South Africa transformed. Nelson Mandela was released in early 1990 and was elected president of a new multiracial democracy in 1994. How important were international boycotts and broader cultural opposition, such as the plotting of Lethal Weapon 2, in ending apartheid?

Did decisions by American moviegoers and consumers, and, importantly, a wider international coalition of politically engaged citizens, contribute to the fall of South Africa’s white-minority regime?

Was the decision by Black teachers in Detroit to divest their pension funds important? Did the Dutch consumers who chose other fruits in place of Outspan oranges have a political impact? How influential were the decisions of British savers to withdraw their funds from Barclays accounts? Can we draw a line between South Africa’s suspension from the Olympic movement and the collapse of the government in Pretoria?

And also, were local boycotts by Black South Africans in Johannesburg and elsewhere important in destabilising the oppressive state?

Opposition to apartheid is the most significant geopolitical transformation of recent history associated with the practices of boycott. There’s a much wider history of boycotts, including the fight against the transatlantic slave trade, the battle for land reform in 19th-century Ireland and the Indian struggle for independence and American civil rights movements. More recently, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to boycotts of Moscow’s banks, oil and consumer products, and within Russia, there have been counter-boycotts of Western goods and services.

Returning to Danny Glover and following his activism can link the boycotts of four decades ago to the most pressing political issues of today. Glover’s political activism didn’t end with a new South Africa.

In 2010, while I was doing field research in Mozambique, he visited a bar in the capital, Maputo. He wasn’t just there to enjoy hot and spicy shrimp and cold beer; rather, he was in the impoverished former Portuguese colony that neighbours South Africa as he has a sustained record of campaigning against poverty in the world’s most impoverished communities. As a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador, he has supported causes across sub-Saharan Africa, including championing local filmmakers with

progressive policies.

In 2013, he won the Audrey Hepburn Humanitarian Award for his advocacy work on behalf of vulnerable children. Moving closer to the present day, his activism has focused on one of the most contentious geopolitical disputes of our times.

In 2018, Glover was highlighted, alongside Viggo Mortensen, as one of the major stars supporting the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign against Israel. These two Hollywood actors were among 79 international artists, writers and producers from across the arts in the UK, the USA, Germany and elsewhere, as well as public figures including Desmond Tutu, Naomi Klein and Noam Chomsky, who spoke out against what they saw as an ‘alarming form of censorship, “blacklisting” and repression’ of pro-Palestinian activists in Germany.

This is just one instance in which he supported the Israel-boycotting project. Glover has long been a supporter of the Palestinian cause, and there’s a strong relationship between the anti- apartheid movement of the 1980s and the ongoing BDS campaigns that target Israel.

Since the horrific Hamas attacks carried out in October 2023 and the utterly devastating Israeli response in Gaza, there has been a surge in support for different types of boycotts – academic, cultural, consumer, divestments, sanctions – as well as occasional counter- boycotts that express support for the Israeli state, especially in the USA. Boycotts have been one of many tools used by Israel’s opponents and some of its supporters.

Do boycotts work? Considering the South African example, it’s an open question whether boycotts were truly influential in bringing about the fall of apartheid or if

it was going to happen anyway. Support for boycotts may have only mirrored an inevitable geopolitical shift that accompanied the final decline of colonialism, the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe, the end of the Cold War and the spread of new liberal economic and political models.

Maybe people such as Glover were well intentioned and joined boycotts because they were attractive and popular, and their participation gave their celebrity career authenticity, while for the general public, this virtuous movement was something enticing and easy to follow, but they didn’t really make the difference. White minority rule was always going to end in South Africa.

Or perhaps it was the opposite: boycotts drew attention to South Africa, caused Pretoria economic pain, and accelerated the collapse of the white government. Moving from the past to the future opens up a prescient question: is it possible that boycotts and movie star activism will play a role in bringing peace to the Middle East?

Imagine the following scenario. You’re browsing the film listings and see the following summary for a new summer sequel: Lethal Weapon 5. In this warmly welcomed reboot of the successful ’80s and ’90s film franchise, series co-lead, maverick cop Martin Riggs, is joined by a new partner, the cool, calm, and professional Rashid Mustafa, as they investigate Israeli arms dealers who have penetrated a corrupt LAPD.

The synopsis is no more sensational than the plot of the Lethal Weapon movie, released 36 years ago, but it would be a bold Hollywood producer who brought such a political film, which paired white and Muslim cops in a crime caper and promoted a boycott of Israel, to today’s cinema screens.

This scenario is a purposeful provocation. Despite the torrent of news stories of suffering in Israel, Palestine and Syria, and the strong support for BDS among minority groups, maybe boycotts have had their moment and dropped out of the mainstream popular consciousness, as we live in increasingly post-political times.