Hen harrier persecution in England continues unabated, as former senior police detective turned wildlife photographer John Birch investigates

Like other raptors in the UK, hen harriers have been subject to persecution since the 1600s. Many were killed because, as their name suggests, they preyed on domestic chickens. Their plight worsened with the advent of driven grouse shooting, which grew in popularity among the wealthy in the mid-1800s.

Gamekeepers were employed to suppress predators – both mammals and raptors – resulting in the complete extirpation of hen harriers from the UK mainland by 1900. They began to regain a foothold between the two world wars, but their return again brought them into conflict with grouse moor managers.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

Since the Protection of Birds Act 1954, all of Britain’s birds of prey have been legally protected. However, according to some, the killing of hen harriers has continued unabated, with law enforcement failing to prevent it or bring offenders to justice.

Opponents of driven grouse shooting, such as Ruth Tingay, author of the Raptor Persecution UK blog, and her co-directors at Wild Justice – author and conservationist Mark Avery and television presenter Chris Packham – assert that hen harriers are being illegally killed in significant numbers. They lay the blame squarely on the driven grouse shooting industry, which they accuse of causing widespread environmental harm.

In 2020, shoot-supporting organisations issued a joint statement acknowledging that a small minority of individuals had tarnished the reputation of their community. It said they ‘unreservedly condemn’ the illegal killing of raptors but denied that it is widespread. The Moorland Association (MA), which represents grouse moor owners, maintains: ‘Sustainable grouse moor management today is a world away from the myths presented by opponents.’

Anyone who watched the recent Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) covert video of gamekeepers planning to – and off-camera – killing a hen harrier, as broadcast on Channel 4 News, would likely disagree.

It wasn’t always this way. In his 2015 book Inglorious: Conflict in the Uplands, Avery discusses a time when most conservationists were generally supportive of

the idea that managing grouse moors had significant benefits. However, this perspective shifted after the 1992 Joint Raptor Study conducted at Langholm Moor, a grouse moor in the Scottish Borders.

The extensive research, funded by the owner, along with various conservation and pro-shooting organisations, took place over five years. It revealed that raptors, particularly hen harriers, were decimating the shootable surplus of red grouse, which compromised the economic viability of driven grouse shooting. In other words, a successful driven grouse shooting business can’t be sustained without killing hen harriers and other raptors.

This is a conclusion strongly contested by the MA. Andrew Gilruth, CEO of the MA, told me that Langholm’s environment and geo-location were unique, and these findings can’t be applied to all grouse moors.

However, the study has had a major impact. Following it, and subsequent studies, the owner of Langholm Moor, the Duke of Buccleuch, ended all grouse shooting. The moor was purchased in a community buyout in 2021 and is now a nature reserve.

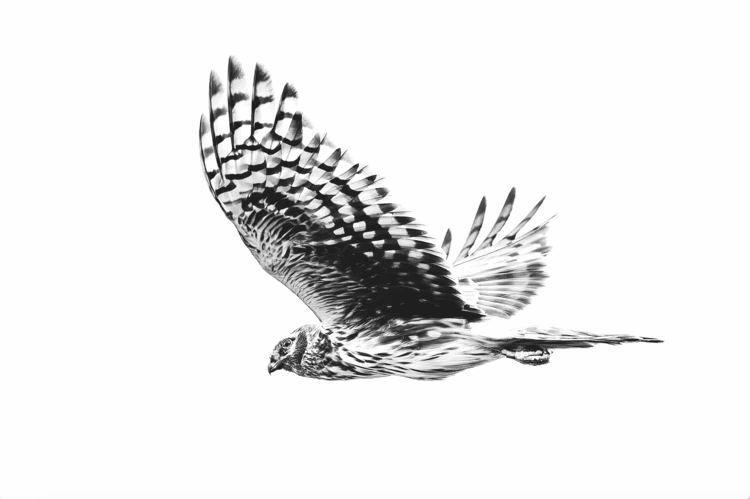

Remarkable birds

The hen harrier is a remarkable bird. Its plumage is so sexually dimorphic that the dark-brown ring-tailed female and light-grey ghostlike male were once considered different species. Anyone who has witnessed their acrobatic, sky-dancing courting ritual and mid-air food passes will never forget it, and it’s something that, as a wildlife photographer, I was keen to document.

I live beside an English grouse moor but had to travel 725 kilometres north to Orkney, where there’s no grouse shooting, for reliable sightings.

Hen harriers are one of England’s few ground-nesting raptors, preferring open land free from predation risks. With historically suitable lowland habitats destroyed over the years by industrialisation, intensive farming, forestry and recreational land use, they, like many other ground-nesting species, have migrated to upland moors where predators are controlled. Ironically, the hard work of gamekeepers provides the hen harrier with its perfect habitat. Their limited territorial range means their population levels are directly affected by illegal killing.

Unsurprisingly, the hen harrier has become emblematic of conservationists’ opposition to the driven grouse shooting industry.

Science suggests that the uplands of northern England should sustain a breeding population of 330 pairs of birds. While all wild animal populations fluctuate according to various environmental factors, numbers are far below what should be expected. However, confirming that crimes have occurred requires hard evidence, such as an eyewitness report, a covert recording, or the post-mortem examination of a carcass to prove the bird has been shot or poisoned.

Given the offences take place away from prying eyes, in remote locations, often on private land, such evidence is hard to come by and someone shooting, trapping or poisoning a bird of prey is unlikely to leave proof of their crime.

However, fitting satellite tags to young hen harriers, with dogs trained to locate the birds or their tags when they stop transmitting, has proved a game-changer. The tags provide a more accurate means of assessing the actual number of birds illegally killed and valuable intelligence about their last known location if a body can’t be recovered.

As the body responsible for nature, Natural England, answering to the Department for the Environment and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), licenses the tags and publishes online updates on the outcomes of the 110 fitted in England since 2013. Since then, only two recovered hen harrier carcasses have actually been confirmed as illegally killed. On one occasion, the offender had decapitated the bird and removed its ringed leg, while, on another, they fitted the tag to a live carrion crow, presumably to indicate that the harrier was still alive and thereby delay detection.

Far more alarming is the number of birds for which a functioning satellite tag ceases transmitting for no apparent reason. Sixty-two per cent of birds are accordingly listed as ‘missing-fate-unknown.’ While some can be attributed to tag failure, predation, or natural causes, 42 per cent of disappearances remain unexplained, giving rise to the suspicion that the birds have been illegally killed and the tags destroyed to conceal the crime.

RSPB-sponsored research indicates that most of these birds are likely to have been illegally killed, and the last transmission is the probable location where the crimes took place. Using a more comprehensive range of tag data, the RSPB assessed that illegal killing accounts for a third of hen harrier annual mortality. The research also links these suspected crimes to land managed for grouse shooting.

Gilruth dismissed the findings and told me he attributed the missing birds to tag failure or other unknown causes. He says that more would be gained if conservationists and shooters focused on converging viewpoints, citing the 2023 IUCN Guidelines on Human-Wildlife Conflict.

He points to the efforts made by his association to work with Natural England on its 2016 Hen Harrier Action Plan and specifically the association’s contribution towards a ‘brood management project,’ removing hen harrier broods, rearing them remotely and relocating the fledglings to moors where there are fewer birds.

A 2023 survey recording 50 breeding pairs in England prompted a recent MA blog post declaring: ‘The population of hen harriers in England reached a 200-year high during the brood management trial. Some still refuse to accept this achievement […] We look forward to the next stage in this remarkable success story.’

Less enthusiastic is Wild Justice, which termed the project ‘brood meddling’ and initiated legal proceedings in a failed attempt to stop it from going ahead. They and the RSPB claim the project is, in effect, giving in to criminals and rewarding the perpetrators for past crimes.

They also believe it’s a stepping stone to licensing lethal control of hen harriers. In a recent blog post, Tingay pointed out that since 2018, at least 129 hen harriers have been killed, and 30 of those were birds that had been moved in the brood management project. She concluded that such deaths can only indicate that the grouse shooting industry doesn’t take hen harrier conservation seriously.

Hardening of attitudes

A 2018 study by the British Ecological Society on the grouse shooting debate found that ‘parties appear to be becoming more polarised in this conflict’, and there was ‘considerable proof that attitudes and behaviour are relatively unresponsive to evidence and knowledge’. While brood management may be a success, by one metric at least, hen harriers are still being illegally killed in increasing numbers, and attitudes have only hardened.

Amid high levels of alleged and suspected criminality, I submitted Freedom of Information (FOI) requests to the Ministry of Justice, Crown Prosecution Service and all eight police forces in northern England hosting grouse moors, asking how many people in England had been prosecuted for offences involving hen harriers. I found that, unlike other crimes, most wildlife crimes are not subject to mandatory recording. As such, no agency had records of a prosecution occurring, successful or otherwise.

The RSPB, which maintains the most comprehensive and reliable register of raptor crimes and prosecutions, validated my assertion that no-one has ever been prosecuted for a hen harrier crime.

The need to plug this data-record gap was highlighted in 2017 by Wildlife and Countryside Link, a coalition of the UK’s most prominent conservation charities, and it appeared as an objective in the National Police Chiefs Council 2022–25 Rural and Wildlife Crime Strategy. Disappointingly, nothing has changed. A former wildlife crime officer told me that whether or not any action was taken in response to wildlife crime depended on the whim of the local senior police officer.

So, how many police officers are dedicated to wildlife crime investigation? Rebecca Pow MP, the DEFRA minister for nature in 2021, stated at the time: ‘There are now over 770 wildlife crime officers in England and Wales.’ As part of the above FOI request, those same eight police forces and the UK National Wildlife Crime Unit (NWCU) furnished much less impressive numbers.

Collectively, they employ 17 police officers, 17 police staff and six police community support officers dedicated to investigating wildlife crime.

That’s 40 individuals for the entire area. Only two are detectives. It seems the former minister might have been confusing practising wildlife crime officers with the total number of police officers who have attended a short course on wildlife crime.

NWCU answers to DEFRA and describes itself as ‘principally an intelligence unit providing operational support to law enforcement.’ Its remit is much broader than just raptor crime, and the efforts of the 20 staff members must be spread incredibly thin.

This number is complemented by a dedicated team of RSPB investigators, numbering 15 for the entire UK, who have, for many years, to all practical intents, led enforcement activity. Unfortunately, the RSPB is a charity with no statutory powers and no trained detectives, and it has been criticised for conducting unauthorised surveillance. Only the police and some government bodies have statutory powers and, as with most crimes, a duty to enforce the law.

In 2021, DEFRA asked the UN’s International Consortium on Combating Wildlife Crime (ICCWC) to assess the UK’s capacity and capability. The ICCWC acknowledged that the UK is a world leader in covert policing but can’t use advanced investigative techniques for most wildlife crimes due to the modest penalty thresholds and a lack of appropriately trained detectives.

IT damningly observed: ‘Wildlife crime is simply not seen as “serious crime”.’

Nonetheless, it acknowledged that NWCU is critical in hosting the multi-agency Raptor Persecution Priority Delivery Group (RPPDG), another facet of Natural England’s Hen Harrier Action Plan. RPPDG membership includes several raptor conservation organisations, the RSPB among them, and several organisations representing game-shooting interests, including the MA.

Detective Inspector Mark Harrison chairs the unit. He told me that he arrived two years ago and found a forum producing, as he put it, ‘a lot of noise.’ He described heated, unproductive arguments where, for example, gamekeepers were accused of randomly killing whatever they wanted and protecting criminals.

The RSPB was accused of planting evidence to suit its narrative. He explained: ‘There was no respect between some of these organisations and certainly no trust.’ Concerning hen harrier crime, he said: ‘The accusation has always been that it is the gamekeepers, but […] there is absolutely no evidence whatsoever of who is committing the crime. It [is] all circumstantial.’

Although he has been pitched into the role of mediator and diplomat, Harrison told me: ‘I have been trying to do it to a point, but I am an enforcer, so I am not independent.’ Harrison acknowledged the RSPB’s passion, enthusiasm and commitment but recognised that he needed to generate credibility and establish police primacy.

With an extensive background in covert policing, he has thought creatively about the problem, potentially overcoming the ‘serious crime’ threshold necessary to deploy advanced techniques. He understands that while killing hen harriers is not a serious crime in law, theft of their high-value satellite tags is so defined.

The crime must stop

Harrison outlined how he has established a mutual-aid protocol between interested police forces to respond promptly to reported crimes. He analysed the ‘missing- fate-unknown’ tag data to map hotspots of suspicious hen harrier disappearances and has personally visited the landowners. He informed them that they sit within a ‘Bermuda Triangle for hen harriers’ and invited them to work with the police to help change that.

He explained that landowners don’t want their estates to be highlighted as hotspots for raptor crime because it’s reputationally damaging, and can attract protesters and result in abuse and threats directed at their gamekeepers.

While few directly accepted his offer, since the visits commenced in 2024, the number of suspicious disappearances is a fraction of the 2023 number,

and encouragingly, no birds have gone missing in hotspot areas. As part of this approach, he found some grouse shooting estates utilising various elements of good practice.

Still, as a measure of how entrenched positions have become, they were reluctant to be highlighted for fear of an adverse reaction from their peers. Tingay recently conceded: ‘I’m sure – in fact, I know – that there are some decent members in [the grouse shooting] industry who abhor the illegal killing of raptors as much as many of us do.’

Unfortunately, while visiting landowners may have prevented crimes, it resulted in criticism from the MA and an exchange of words that eventually saw Gilruth expelled from the RPPDG.

In addition, key actors have recently withdrawn from other multi-agency, pro-raptor partnerships. Wild Justice continues to call for driven grouse shooting to be banned and last month launched a petition calling for a parliamentary debate on the issue. The RSPB’s position is that all driven shooting should be licensed and regulated.

Meanwhile, most landowners are now refusing to allow access to their land for the fitting of satellite tags, and the MA is pursuing post-project brood management licensing without the support of many conservationists. Divisions remain deep, and the future looks bleak.

Everyone involved in the topic feels pressure. By way of example, in 2023, United Utilities, which provides water in the Northwest, announced that it would not renew leases for shooting on its land. Another major landowner, the National Trust, has cancelled leases in cases where there was evidence of raptor crime and has implemented restrictive conditions on all game shooting across its properties.

The IUCN guidelines cited by Gilruth recognise collaboration and co-management as critical in every human–wildlife-conflict scenario and that deeply entrenched positions can’t be resolved without a high degree of skilled diplomacy. The specialist contributor to the guidelines on nature conservation and law, however, says: ‘It is clear that the role of law in respect of conservation conflicts should not be underestimated.’

The personal impact on convicted offenders, including the possible loss of job, house, car and reputation, demonstrates the importance a successful prosecution for raptor crime could have. Not only would it remove or scare offenders, but in doing so, it would empower law-abiding members of the shooting community and conservationists. A conversation based on evidence could begin.

As it stands, hen harriers are being illegally killed and no-one is being prosecuted, and that failure has driven people away from the table. As Harrison explained: ‘We are not going to get anywhere unless the crime stops.’ He added that if driven grouse shooting relies on committing a crime to survive, ‘it is going to have to amend its business plan’.

Using the few tools at his disposal, he has built up an impressive momentum for change, assembling the necessary building blocks for advanced enforcement action. Still, he will need further government support to convert this into tangible results.

While the many competing demands on English policing can’t be ignored, the modest costs of introducing crime recording, increasing penalties and a slight uplift in numbers could transform these efforts. Implementing the IUCN guidelines on co-existence and the ICCWC recommendations on law enforcement are within DEFRA’s gift. We invited comment from the current minister for nature, Mary Creagh MP, but received no reply.