The exact reasons behind warming spikes seen in 2023 and 2024 have left scientists stumped, as 2024 set to be hottest year on record

By

The planet is, undeniably, getting hotter. Last month was the second-warmest November on record, with the month also marking a record-high monthly average temperature for 10.6 per cent of the world’s surface. So far this year, six continents have had their warmest temperatures on record, and 2024 is set to be the hottest year yet.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

While climate scientists are all too familiar with the trend of our planet’s uptick in temperatures, there is growing confusion over explaining how vast these temperature spikes have become in recent times – in particular, in 2023 and 2024.

To tell the full story, let’s rewind back to September 2023: the month that one scientist described as ‘absolutely gobsmackingly bananas’.

Across the world, scientists were stunned by the fact global average surface temperatures for the month rocketed above the previous record-high temperature by 0.5C, the largest jump in temperature ever recorded. At the time, the temperature shift was attributed mainly to human-caused global warming and El Niño (when warm surface waters release additional heat in the atmosphere).

A year on, the planet’s temperature is still rising – even after El Nino ended in May this year – at levels that baffle scientists. Last week, in the year’s largest climate science conference, the vast majority of those in attendance believed that a sufficient explanation of these anomalous spikes hadn’t been offered.

Theories explaining the spikes range from strong El Niño events to changes in low-level cloudiness. Another hypothesis linked rising temperatures to a pollution reduction measure which altered the quantity of sulphur in marine shipping fuels.

While it may be intuitive to think traditional ‘dirty’ fuels (containing sulphur) only cause harm to our environment, they actually have an unintended side effect of cooling the planet. To what extent is unknown, but this has led some to consider it one factor in the planet’s rising temperatures.

This is because these sulphur-containing fuels increase background sulphur aerosol levels (droplets suspended in air). Once water vapour condenses on these aerosols, they form clouds. Clouds polluted with sulphur are typically brighter than their clean counterparts, meaning more light can be reflected back into space and consequently reduce global warming.

Although patterns in the study’s models correlated strongly with satellite-observed changes in clouds, scientists are eager to point out that rising temperatures across the planet – and the spikes seen in 2023 and 2024 – cannot solely be accounted for by changes in shipping fuel regulations alone.

Some scientists entirely caution against using the sulphur fuel argument to explain rising temperatures: ‘It’s hard to make the case that the [new shipping fuel] regulation in 2020 would create a sudden jump in 2023 that we didn’t see in 2022,’ said climate scientist at Berkeley Earth Zeke Hausfather.

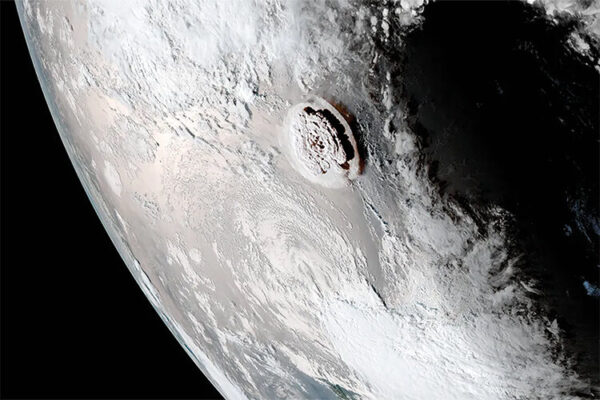

Other factors considered as explanations for the spikes include the solar cycle – in which the sun is currently at, or near a peak in its activity – as well as the eruption of the underwater Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha‘apai volcano in January 2022 which sent water vapour into the stratosphere (an event that could lead to warming effects).

For NASA’s chief climate scientist, Gavin Schmidt, though, not one of these reasons – or even a combination of them all – feels a sufficient explanation for the temperature spikes. That could mean that a factor not studied before could be to blame, or potentially that the climate is far more unpredictable than first thought. Climate models used by scientists may also be more inaccurate than we think.

Whatever the reason for these spikes, scientists are concerned. Such anomalous shifts in temperature could mean fundamental changes are happening to the climate, so that its behaviour is not in line with predictions and models. A stark deviation between the reality of the planet and models poses a real problem: climate scenarios which form the basis for countries’ climate-friendly goals could be incorrect, meaning higher warming levels and environmental impacts occurring far sooner than expected. According to Schmidt, these spikes suggest we will reach the 1.5-degree celsius global warming threshold sooner than anticipated.

So, as we enter 2025 – a year scientists believe will be one of the top three hottest on record – the data is clear. The planet is warming.

But what remains far more nebulous is understanding exactly why: a puzzle climate scientists must continue to piece together through ongoing research and analysis.