Norwegian government has agreed to postpone first licensing round for deep-sea mining in Arctic waters after mounting pressure

By

The Norwegian government has postponed its plans to carry out Arctic deep-sea mining across an area equivalent in size to Italy, following backlash from international organisations, activists and scientists.

Back in January, the government opened up for deep-sea mining exploration in the Arctic, in an area between Svalbard and Jan Mayen Island – and in June, it was announced they would grant the first licenses to mine in early 2025.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

But strong reaction from the international community strengthened in numbers following the decision, with 119 European parliamentarians writing an open letter to Norway to ask for the opening process to be stopped.

‘Stopping the Norwegian deep sea mining plans is an important step in stopping this industry from destroying life at the bottom of the sea,’ said deep sea mining campaigner at Greenpeace Nordic Haldis Tjeldflaat Helle. ‘Any government that is committed to sustainable ocean management cannot support deep sea mining.

‘It has been truly embarrassing to watch Norway positioning itself as an ocean leader, while planning to give green light to ocean destruction in its own waters.’

Steve Trent, CEO of the Environmental Justice Foundation, said: ‘While today is a cause for celebration, this victory must not be seen as the end of the struggle, as the licensing in Norway is only blocked until 2026. We must now work together to ensure that this decision becomes permanent.

‘We urge Norway’s government, and all responsible global actors, to make this a lasting victory by enshrining protections for the Arctic Ocean and its ecosystems into law, and coming out in favour of a moratorium or ban on deep-sea mining.’

Why do countries carry out deep sea mining?

Countries’ interest in deep sea mining has grown in recent years as the transition from fossil fuels to cleaner energy sources takes centre stage. This is because precious metals such as nickel, cobalt and copper – required to make low-emissions products like electronics – can be found deep within ocean waters on seabeds, seamount crusts and hydrothermal vents.

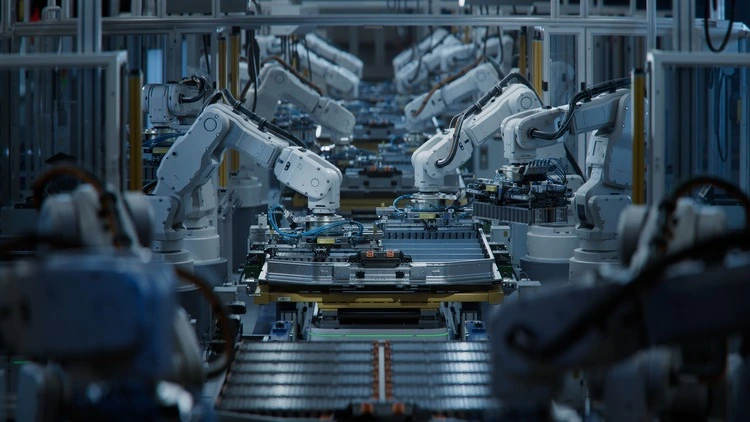

While deep-sea mining might sound like an easy fix to environmental problems, it may also cause more harm than good. Because the process of extracting metals is so intensive – requiring large robotic machines to excavate the ocean floor, similar to strip-mining on land – the excavation process will inevitably have a significant environmental impact on marine life and ecosystems in the areas it is carried out.

Biodiversity loss, noise and light pollution, as well as potential repercussions on carbon sequestration, are all understood to be implications of deep-sea mining.

Ultimately, scientific research is relatively light on deep-sea mining – and this is what causes most of the concern among scientists, who believe the extraction of metals and minerals should not go ahead until the full picture of risks – social, environmental and economic – are entirely understood.

A permanent fix – or not?

Although Norway’s plan to carry out deep-sea mining has been suspended for at least the whole of 2025, the Norwegian government has stated it will continue to carry out preparatory work for the project, such as understanding environmental impacts and creating regulations.

And as Norway’s election is in September next year, the concerns of environmental organisations and scientists grow as both opposition parties currently leading in polls – the Conservatives and the Progress Party – are both pro-deep sea mining. If these win against the Norwegian currently-elected Labour Party, this could spell bad news for completely halting deep-sea mining.

Even if Norway continues to halt the ban on deep-sea mining when its government is elected next year, there are still other countries on the deep-sea mining scene. 30 exploration contracts have been handed out to 20 countries across the world so far. China and Russia take the top spots, with 5 and 4 contracts, respectively, followed by Korea (3), France (2) and Germany (2).

Current areas that are being vied for commercial interest include the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, a region in the Pacific located between Hawaii and Mexico, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the Northwest Pacific Ocean, and the Indian Ocean. Combined together, these regions are home to 11 deep-sea mining exploration contracts alone.

There is, however, growing strong opposition to deep-sea mining, with 31 governments – led by Palau, Fiji, Samoa and the Federated States of Micronesia – calling for either a pause, ban or moratorium on deep-sea mining until it has been further studied.