Written by Sophie Donovan

Best-selling author Tim Marshall is making complex geopolitics accessible to a younger generation with an illustrated version of Prisoners of Geography

By minute three of my conversation with Tim Marshall, the subject of his new book has been dropped as the main topic of conversation, replaced instead by the centenary year of Leeds United. That and our shared obsession with Sky Atlantic’s Chernobyl. It was hard to believe that the northern, season-ticket holder at the other end of the phone was a leading expert in anything geography, history and politics related.

Stay connected with the Geographical newsletter!

In these turbulent times, we’re committed to telling expansive stories from across the globe, highlighting the everyday lives of normal but extraordinary people. Stay informed and engaged with Geographical.

Get Geographical’s latest news delivered straight to your inbox every Friday!

You’d be committing blasphemy if you said this to Tim Marshall’s face however. ‘Now I’m not an expert, but I do have experience,’ he says. ‘I’m lucky enough to be able to convey complicated stuff in an accessible manner. So perhaps, forgive me for praising myself, but I’m an informed communicator.’

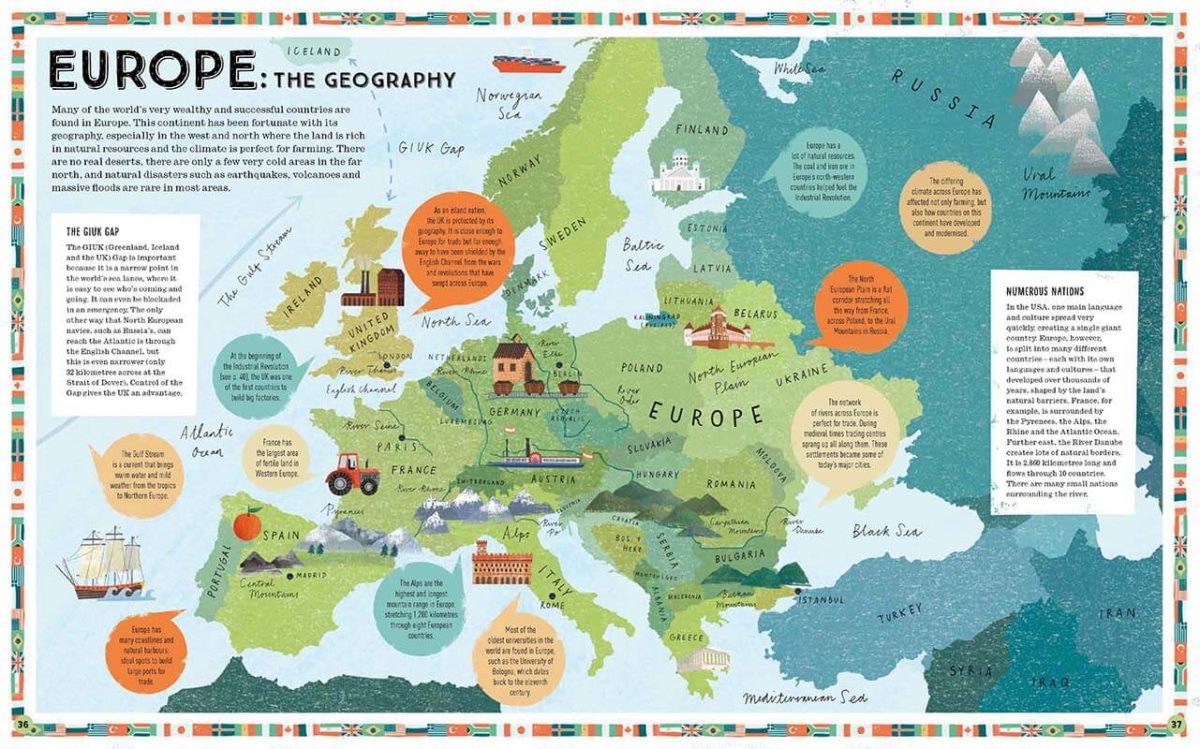

The 60-year-old journalist-turned-author is best known for his number one Sunday Times bestseller, Prisoners of Geography. The map-focused non-fiction title explains the intersection of geography, history and politics, and how all combine to create society as we know it. Originally published in 2015, Marshall is gearing up for the release of a version of the book aimed at the next generation.

Was it always the plan to write a children’s book?

No, no not at all. But a couple of things happened. I had this terrific response to the original publication from people taking their GCSEs and A-levels. Obviously, all sorts of people bought it. When I was giving talks at schools or unis or book fairs or whatever, I had this amazing response over and over again. An undergraduate might come and say: ‘oh I read Prisoners of Geography at school and it inspired me to study geography,’ or maybe international relations at university. And so, I took that concept and thought, well, you know, if young people are inspired by what I hope is an accessible approach to these big issues, perhaps younger minds could be as well.

So why this style of children’s books, with maps and facts, not games aiding the development of the senses?

Well I was led, happy to be led, by my publishers Elliot and Thompson because this is not something I am an expert in. They came up with this style. I love the idea of it because there are children who are captivated by maps, and so here is a way of engaging them but giving those maps the context they require. You know, you’re not just looking at a map. There’s text alongside it, it’s telling you more about what you are looking at. And then the following page will give you more pictures and contextual text.

I can see myself when I’m nine or ten year’s old happily sitting down for several hours on a rainy afternoon and just pouring through this and using it as jumping off point for a million other things.

What was the hardest chapters for you to write?

Probably those on the Middle East and Africa. The two different chapters are dealing with colonialism and religious divisions and, let’s be fair, troubling times. To boil that down without oversimplifying it was a real challenge. And also, not to inadvertently say something which might be too broad and insulting.

You know, the world is a beautiful place and children often know that. This book is helping to understand complexity, but I didn’t want to get into too much of the detail of this. The serious difficulties. That was a real challenge, to get that across and still make it light and yet informative.

How have you found adapting complex material to younger audiences?

Distances and time are two things that younger children can struggle with. ‘Oh, how far is 100 miles’ or whatever. But telling somebody that it would take six nights and seven days to travel by train from Vladivostok to Moscow. That sort of ‘oh wow, I have to be on a train for six nights, for seven days, that’s how big it is?’ I like things like that – that has the ‘ooh’ factor.

Where did your interest in geography, politics and international relations stem from? Is there a pinpoint moment?

I assume it evolved from childhood. I just ate up fiction and non-fiction books. I loved atlases. And there were a few moments where, this is not geographic, but I remember Martin Luther King’s funeral. And I was only nine so obviously I wouldn’t have understood it, but it just had this impact on me. Like, ‘oh what’s that all about?’ And another one, I remember the Moon landings when I would’ve been about ten. And I remember the first time I came across footage from Auschwitz when I was about 11. At approximately aged 12, I first heard the BBC recordings of the D-Day landings. You just put all that together and it produced, with many other things, an abiding interest in how the world works which I suppose then led me towards eventually becoming a journalist.

Subscribe to our monthly print magazine!

Subscribe to Geographical today for just £38 a year. Our monthly print magazine is packed full of cutting-edge stories and stunning photography, perfect for anyone fascinated by the world, its landscapes, people and cultures. From climate change and the environment, to scientific developments and global health, we cover a huge range of topics that span the globe. Plus, every issue includes book recommendations, infographics, maps and more!

What was the hardest story you had to report on as part of that job?

There was just one incident in a hospital in Baghdad with a mother imploring me, this funny-looking foreigner who has just rocked up who was clearly, in quotation marks, important, imploring me to save her dying child who was about two. That utter feeling of helplessness. That wasn’t easy.

What experiences as a journalist helped shape Prisoners of Geography, both the previous and the new?

There was this moment in the Bosnian war when I saw a village on fire and asked the people that set it alight why they’d done it. They said: ‘Because we need everyone to get out of that village and the one next to it. Obviously, if they see the next village on fire, they’re going to scarper. Because we need access to this valley to reach a major road.’

And it was sort of, I mean, it is obvious. But many things are not always apparent, if you see what I mean. It is obvious that there is a geographical underpinning to many events, but it was just the starkness of that moment. It never left me. And so pretty much every international story I ever covered subsequent to that was through the prism of explaining what is going on there. It’s geography in its widest sense. I just found it helped me so much to understand the dynamics of pretty much any given situation.

Using your geopolitical expertise, what do you hope for geography, history and international relations?

Well, we periodically go through turbulent times and that’s why they make history. It’s why we sit up and take notice. But in between there are long stretches of calmer times in which great progress is made. If history goes in waves, we will come out of this wave and we will carry on doing what we’ve done as a species for the last several centuries, which is rapidly improve.

It is a particularly turbulent and divisive time. That’s why I wrote Divided (in 2018), because I just felt that all the walls and the fences that have gone up are the physical manifestations of this divided time.

But we go through these periods, and so based on most of things that have happened, I think it’s okay to come down on one side of the argument. That the probability is that we will come out of it and carry on, with things getting better.

It’s an optimistic viewpoint, certainly.

I’m not a doom-monger, despite writing about doom and gloom quite a lot. I’m actually relatively optimistic that in the grand scheme of things we keep going in an upward direction.

What are you hoping for the kids that read this new version of Prisoners?

I hope it just gives them a geographic or historic context for what they’re seeing in front of them, and that it will lead to many different paths. It doesn’t really matter which one of them you follow. That fact is that if it’s opened a door in your mind, or if it leads to a path that grabs you, that’s one of my definitions of success.

Prisoners of Geography: Our World Explained in 12 Simple Maps