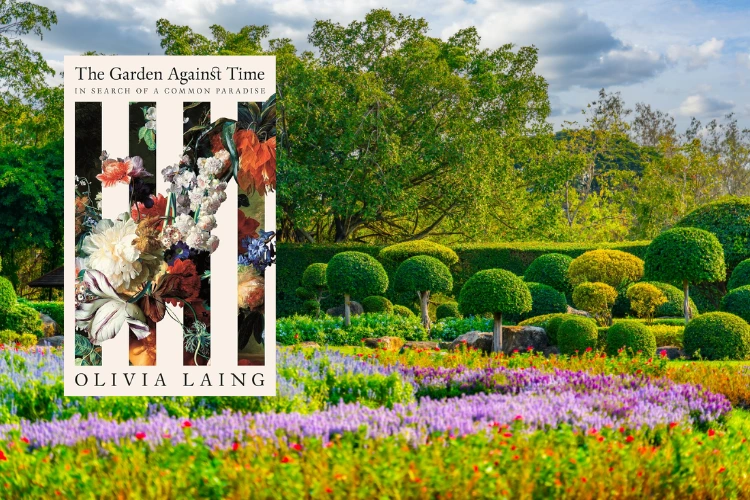

Olivia Laing mediates on the importance and irresistible allure of gardens across history in her latest work

By Olivia Edward

In the summer of 2020, at the height of the COVID pandemic, Olivia Laing found herself a sanctuary, a neglected Suffolk garden attached to the Georgian house she’d just bought with her husband.

‘The entire plot was just under a third of an acre, but it felt much larger because it had been so cunningly divided with hedges… so that you could never see the entirety at once but continually passed through doorways and arches into secretive new spaces.’

Enjoying this review? Check out our other recommended reads:

As she set about its restoration – enjoying the birds ‘chitting’ in nearby shrubbery, giving the experience ‘a pleasant feeling of not-alone-ness, of being accompanied by small invisible presences’ – she began a parallel literary task investigating the allure of gardens, and what they had come to represent to us both psychically and culturally.

She’d always been intrigued by the link between gardens and notions of paradise. Pairidaēza, meaning ‘walled garden’, first appeared four millennia ago in Avestan, an ancient Persian language. It then morphed into the Greek word paradeisos and was used in the Old Testament to mean both celestial heaven and the Garden of Eden. ‘Discovering this chain of association blew my mind,’ writes Laing.

‘It was the garden that came first, heaven trailing in its wake. That had been the acme of perfection, the ideal across centuries and continents: an enclosed garden, a fertile, beautiful, cultivated space.’

It’s in these territories that Laing excels, writing in sumptuous prose, plunging in and out of subjects, taking us with her on the thrilling chase across history and geography, seeking out associations. Donald Trump makes an appearance, as do William Morris, Milton, Capability Brown and many more.

She’s open about the moral complexities of gardening but would still have them at the centre of any regenerative utopian dream, acting as they do, like the art shack at Derek Jarman’s school, as ‘a defence against an everyday existence that was awry.’