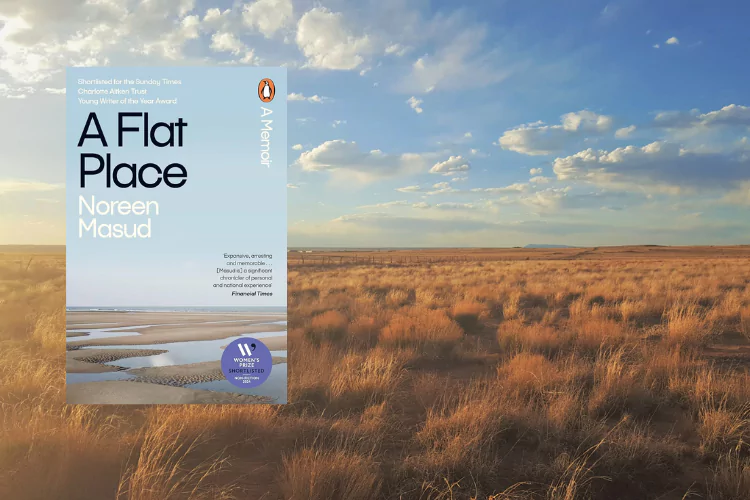

Noreen Masud’s latest book uses the power of landscapes to conjure a compelling memoir on personal histories and trauma

By

As landscapes, flatlands have rarely been thought of as charismatic places. Prototypically, geographers are called to mountainous terrain. The ascent of faraway high peaks makes for the most evocative images of expeditions and fieldwork, and symbolise the disciplines’ colonial origins. Rugged, undulating physical geography is the zone where dynamic geological formations and geomorphological processes are rendered visible and capture the interest of environmental scientists.

Mountain vistas inspire tired hikers and instil a sense of wonder. Even gentle green rolling hills and valleys engender feelings of calm and contentedness in casual walkers. By contrast, for memoirist Noreen Masud, it is the flats, the level places where land and sky meet in a perfect linear horizon that offer an abundant sense of belonging and solace.

As a child in Lahore, she faced the trauma of a singularly abusive father who kept Masud, her mother and sisters largely confined at home outside school. This was different to the world around her and far from the ordinary, loving Pakistani family upbringing. At school and beyond, she missed opportunities to socialise. Her mother was Scottish and, in the house, as in school lessons, she only ever spoke English and missed out on developing Urdu, further isolating her.

Enjoying this review? Check out our other recommended reads:

In the journeys back and forth to class, it was ‘the green misted fields glimpsed from the car window, stretching out wide and far away’ and another horizontal plane, ‘the flat stone floors of the house’, on which she would lie every day, that marked the formative and hard boundaries of her youth. Later, she came to the UK to study and then, once settled, journeyed through Britain’s flatlands.

Moving more freely, yet with social obstacles to navigate, Masud documents her wanderings through space and memory in the beautifully written A Flat Place.

Grappling with her past while offering a fresh and intimate perspective on landscapes that have their own uneasy histories, her narrative provides a new way of seeing places such as Morecambe Bay, Orford Ness, the Orkney Islands and the Fens.

A century ago, in 1925, cultural geographer Carl Sauer coined the phrase ‘cultural landscapes’ and explained the concept in the following terms: ‘Culture is the agent; the natural area is the medium; the cultural landscape the result.’ Sauer’s writing was formative in reshaping how geographers think about the interplay of human and physical forces in making places. Masud’s writing about the Cambridgeshire Fens follows the same logic as she characterises these seemingly natural places as something socially produced. Still, she goes beyond Sauer to consider how landscape feeds back and shapes our identity.

We think of places such as the Fens as rural, yet that flatness derives from intensive human intervention. The fens were drained at great effort and expense;

the smooth green landscape that was left behind is kept that way with high walls, regular inspections and dredging of canals.

Nature and culture intertwine indissolubly in the fenlands, just as every person does. What happened to you silts invisibly into any original, natural self that predated it.

Britain’s flatlands bear witness to both recent human disasters and faint traces of coloniality. When walking, and later wadding across Morecombe Bay, Masud reminds us of the tragedy in 2004 when at least 21 trafficked people from China drowned in the rising water. They were cockle-picking and unfamiliar with the extreme dangers of the rising tides; they couldn’t communicate when they called 999.

Like Masud, they were isolated by language from the cultural world around them. One Chinese man was convicted of manslaughter and jailed, but the two English men

who had agreed to pay the untrained workers £5 per 25 kilograms of cockles weren’t. In a very different, urban flat landscape, the Town Moor, a 400-hectare urban common in Newcastle, hosted the 1929 North East Coast Exhibition of Industry, Science and Art; its exhibits included an ‘African village’ – a human zoo inhabited by 100 Senegalese people.

Both instances show how people of colour have always lived and struggled in Britain’s flat places, shaping these cultural landscapes.

Through her memoir, Masud primarily tells her own story, rather than narrating the scares on the landscape. She is conceptualising her own complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). This condition arose from prolonged and repeated exposure to traumas as a child – an inescapable flatland rather than the extreme peaks and troughs of episodes of shock and suffering that trigger PTSD.

A Flat Place is a personal and moving work adjacent to the best of writing in social and cultural geography. Although it would be misleading to situate it within the discipline, it exists as something that shows how one person can tell their own story through landscapes.

By taking us with her on that journey, she gives an insight into flat places. Masud’s memoir is a testament to the power of personal narrative and a challenge to conventional understandings of trauma.