In this extract of Maxim Samson’s Invisible Lines, we take a look at some boundaries keeping us apart, and some bringing us together

Every day, each of us encounters and crosses invisible lines that shape how we act, how we feel and how we live. These lines rarely appear on maps and, when they do, have impacts that go far beyond what is generally shown. Consider a ‘no trespassing’ sign: even without the presence of a material barrier, we know not to step any further and that to do so could have consequences.

In Invisible Lines, Maxim Samson looks at 30 such divisions, which reveal the extraordinary way in which we make sense of the world. In some cases, these boundaries affect millions of people across thousands of kilometres, while others are so subtle as to be perceptible only to a small population, to whom they nevertheless have great significance.

MAKING THE PUBLIC PRIVATE

Eruvim – ritual enclosures

Crossing Broadway, one of the main streets running west to east through Williamsburg in New York’s borough of Brooklyn, can be a bewildering experience. The coffee shops, wine bars and Instagram-friendly brunch spots beloved by hipsters quickly give way to discreet synagogues and bustling kosher butchers and bakeries. Shtreimels (fur hats) take the place of trilbies and beanies; frock coats replace flannel and denim. But there is a much more subtle boundary here, too, a wire of enormous relevance to one side yet seldom noticed by the other.

This wire makes up part of the Williamsburg eruv (plural eruvim or eruvin), a ritual enclosure that allows thousands of observant Orthodox Jews to practise their faith as desired on Shabbat, the Jewish Sabbath. The Torah prohibits Jews from working from Friday sundown to Saturday sundown, a rule that includes carrying any object between private and public domains. The dilemma is clear: how can one leave the house to walk to synagogue, possibly with a child in arms or pram, a walking stick or a wheelchair? And what to do with the house keys? Many people would be confined to their homes. An eruv (roughly meaning ‘mixture’) removes this predicament by redefining any space within the enclosure as a single private domain during Shabbat. Not only wires but pre-existing walls, fences, railway lines and even rivers can be used to delineate this space, creating a sort of ersatz building, with vertical posts or poles representing the door-posts.

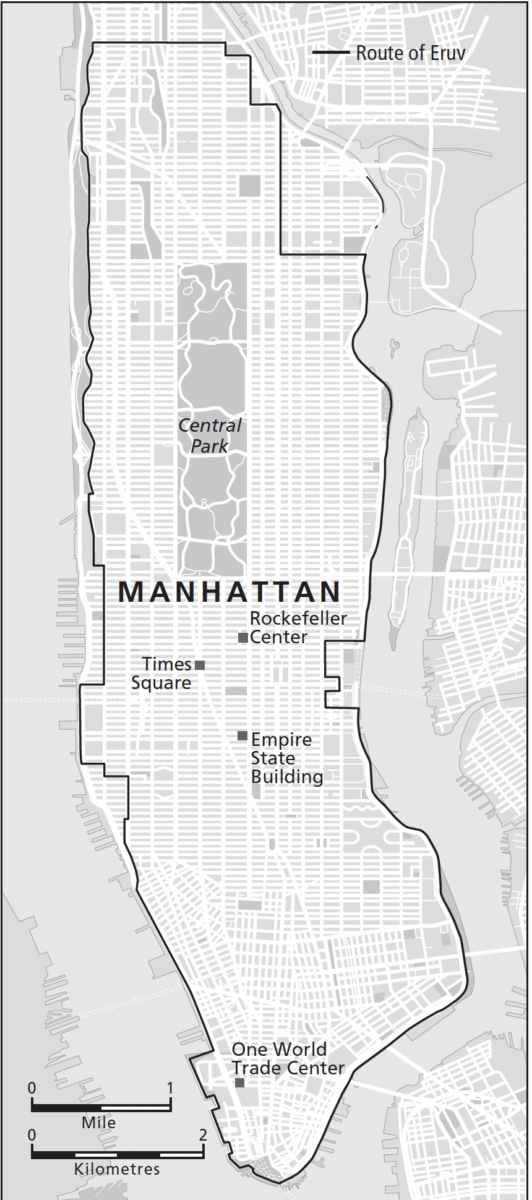

As a result, any space that we may conventionally regard as public (streets, parks, pavements) becomes private to strictly observant Jews as long as the eruv’s boundaries are unimpaired. Every week in advance of Shabbat, a rabbi or other community authority will inspect the entire length of the eruv to ensure that no part of the wire has fallen or been broken: even one collapsed wire renders it deficient, necessitating a speedy repair. In an intriguing juxtaposition, many Jewish congregations that eschew electricity on the Sabbath itself have established social media accounts dedicated to monitoring and reporting on their eruv’s condition throughout the rest of the week. After all, this can be an exacting task for one person, considering that some eruvim are surprisingly extensive and are often located in busy urban areas: the Manhattan eruv, for instance, stretches across the majority of the borough.

This fact may come as a surprise, yet Manhattan is far from an anomaly. The Washington, DC eruv, for instance, contains more than half of the district, including all of its most famous sites. The West Los Angeles eruv covers more than 250 square kilometres. Brooklyn is reckoned to comprise at least ten different eruvim, several of which adjoin one another. Eruvim can also be found in dozens of other American cities, most major settlements in Canada, a number of key Jewish population centres in Latin America and Europe (although, quite surprisingly, not Paris, Berlin or Budapest), select districts in Australia and South Africa, and almost every town and city in Israel.

Although strictly Orthodox Jews are often portrayed as a somewhat homogeneous group, in reality they comprise numerous denominations with contrasting understandings of the key Jewish texts and rituals. This brings us to another way in which eruvim constitute important boundaries within Judaism itself. According to Jews who might be described as more secular-minded, eruvim risk encouraging ghettoisation, attracting antisemitism, or simply bringing down property prices. By contrast, some Orthodox Jews claim that eruvim enable their co-religionists to circumvent what they deem the proper observance of the Sabbath and contribute to what they perceive to be a watering down of Jewish practice, while others argue that many of the eruvim fail to meet their own exacting standards.

Moreover, while these enclosures do not purport to exclude those with different beliefs or require non-adherents to recognise them, they have stimulated considerable contestation where they have become more widely known because of what they are presumed to represent. In particular, plans to construct eruvim have been resisted by those who claim that they constitute an attempt to seize territory for a religious minority (and one that barely integrates with the wider society), as challenging a sense of local place identity, and as implicitly suggesting that all ‘outsiders’ are unwelcome. Protests against the presence of eruvim are not unheard of, even attempts to compromise them through surreptitiously clipping the wires.

That said, eruvim can be difficult to spot, considering that they are typically made up of utility poles and translucent wires, and many who live or work within them are unaware of their existence. When they do notice them at all, most people simply dismiss them as wires and posts, but to strictly observant Jews they define the ease with which they can practise their faith and help balance the challenges posed by a commitment to centuries of tradition and living in a modern society. The fact that they additionally assume a temporal dynamic through only existing for a matter of hours each week, the rest of the time being inconsequential to even the strictest believers, makes them all the more interesting.

HOT & COLD

The Qinling-Huaihe Line

There is a noticeable chill in the air and a thin layer of frost dusts the fields. It’s that time of year again: better wrap up warm for the long, bleak winter to come. Just a few kilometres to the north, the winter will be no less frigid, but the mood is different. Warmth pumps through the houses like a toasty hug. Still, nothing’s perfect. While those to the south will be digging for layers, the residents here will be rummaging around for their facemasks. The problem is not disease – well, not the primary problem. The real issue is the smog that will soon envelop the town.

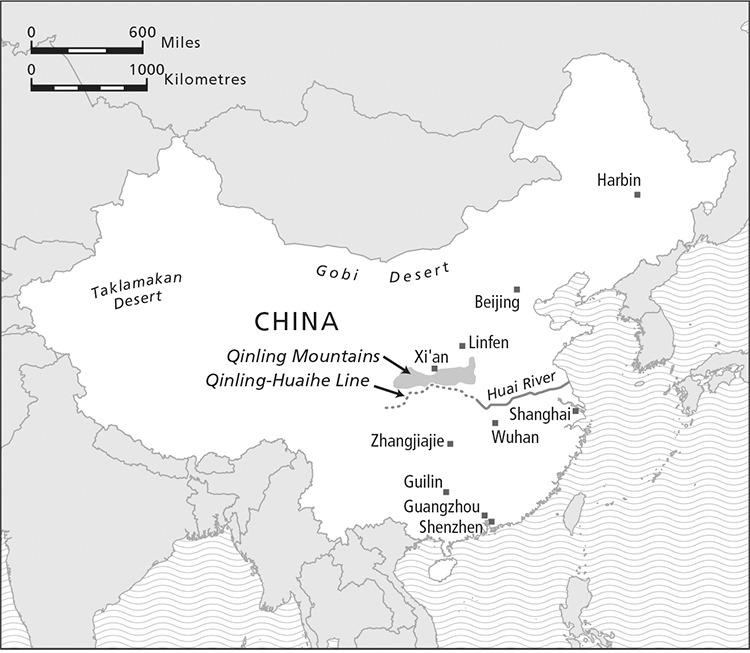

The Great Wall may be the most famous boundary in the world, snaking for well over 20,000 kilometres across northern China and parts of Mongolia in order to repel invaders. A more obscure (and invisible) boundary is the Heihe-Tengchong Line, which was drawn by a Chinese geographer named Hu Huanyong in 1935 to divide China diagonally from northeast to southwest into two portions with widely contrasting population densities. Even though migration, especially towards the southeast, has altered Huanyong’s figures in the interim, the line still represents an illuminating partition, with around 95 per cent of the country’s population concentrated in a smaller area than their compatriots to the northwest. However, a different line plays a role that, although seemingly mundane, is even more significant in the lives of many of China’s 1.4 billion inhabitants today.

Running along the Qinling Mountains in the west before following the course of the Huai River, the Qinling-Huaihe Line was drawn in 1908 by the future founder of the Geographical Society of China, Zhang Xiangwen, to demarcate the country’s north–south divide. In China, this partition takes several forms. For centuries, the north was more developed and is home to the majority of China’s most famous historical sites, including the ancient capital of Xi’an and its Terracotta Army, the Forbidden City of Beijing and, of course, the Great Wall. By contrast, the south has long been renowned for its natural landscapes, although the country’s economic reforms in the 1970s have since transformed its major cities.

The climate also differs from north to south: the former is generally cooler and drier, whereas the latter is mostly characterised by a hot, humid subtropical or tropical climate, depending on one’s proximity to the South China Sea. The Qinling-Huaihe Line relatedly marks quite accurately both the January 0°C isotherm (that is, the line distinguishing places whose average January temperature is below zero, and which are hence prone to freezing, from places whose average January temperature exceeds this figure) and the 800-millimetre isohyet (the line dividing places where annual precipitation is below this amount, from those where annual precipitation is greater).

Given crops’ reliance on specific climatic conditions, there are implications for cuisine, too, with wheat-based items such as noodles, steamed buns and dumplings common in the north whereas rice dishes have a longer history in the south. There are many countries with a north–south divide, but few, if any, pertain to as many subjects.

However, in the 1950s, the new Communist leadership saw the potential for the line to determine rather than merely describe difference, and used it to distinguish between places that would receive a district heating system (to the north, where it was deemed a necessity) and those that would not (to the south).

In many places this is not unreasonable: the southern cities of Guangzhou and Shenzhen, for example, have average minimum winter temperatures of around 10°C, quite comfortably above freezing. By contrast, each winter, Harbin in the far northeast is cold enough to host an international festival of ice castles and mythological snow sculptures. The issue is that many communities near the line face a practically identical climate, but because of the simplicity of using such a boundary as a cut-off point, they are given vastly different resources to cope with it. This divide remains to the present day. Even in Shanghai, China’s economic powerhouse, many of the poorest members of society are forced to encase themselves in coats and quilts as protection against the cold, because they live narrowly south of the Qinling-Huaihe Line and cannot afford a higher electricity bill.

However, the residents north of the Qinling-Huaihe Line are not without their grievances. Although they enjoy the benefits of free or heavily subsidised heat, the most common source over the past half-century – the coal-fired boiler – produces considerable amounts of air pollution. The figures make for grim reading: almost all the most polluted cities in China are north of the line, with some having among the foulest air in the world. Admittedly, there are various reasons for the poor air quality in the north – many cities here are surrounded by mountains that prevent the wind from dispersing pollutants, while Chinese farmers often burn the straw in winter following the harvest (even though this has technically been illegal since the 1990s) – but coal-powered heating is regarded as the biggest cause.

As a result, during winter, smog is a severe issue, obscuring the view of all but the brightest neon signs in major northern cities. Most seriously, the dangerous particulate matter – both fine (PM2.5) and coarse (PM10) – emitted in the north has increased residents’ risks of cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, and has greatly contributed to an average life expectancy that is well over five years shorter than south of the line.

Gradually, improvements are being made. Many northern cities, including Beijing, have transitioned to natural gas or electricity instead of coal, and new targets have been set to reduce particulate-matter emissions. In cities such as Linfen, some residents have even been forced to go cold turkey as their traditional coal-burning stoves have been confiscated by local officials.

Meanwhile, some southern cities, such as Wuhan, have been trying to develop their own unified heating systems, and renewable-energy sources such as wind, solar and biomass are becoming commonplace, in part to stymie frequent calls for the same types of district heating that have acted as a double-edged sword in the north. Previous proposals to push the line further south have consistently been rebuffed on account of expense, but with recent interest in new energy sources, it may be that this boundary fades in relevance over the coming years. For the meantime, however, there is a distinct disjuncture in heating capacity between north and south, owing to a divide as simple as a line drawn from west to east.

STREET LIFE

The gang territories of Los Angeles

Los Angeles, a city that brings up associations with Hollywood and food, sandy beaches and a balmy climate, is also notorious for its sinister underbelly, a complex and shifting terrain of alliances and rifts, racism and violence, widely romanticised in music, video games, TV and more: today one can even participate in a ‘gang tour’ to explore what are often little-known parts of this sprawling metropolis.

And yet many gangs operate right under the noses of the city’s tourists. Parts of the city that in the daytime are regarded as leisurely neighbourhoods, with popular cupcake bakeries, pricy boutiques and hip coffee shops, at night become menacing hoods. Other districts are less fortunate: even in the light they are perceived as ‘dark’, mysterious spaces, familiar only in name and seen solely in news reports.

Those who inhabit areas of the city that are prone to street gang activity are acutely aware of the intricacies of their local geography and the boundaries that divide ‘safe’ from ‘unsafe’ spaces. In some ways, these boundaries are marked, albeit quite subtly, in graffiti tags and murals intended to claim ‘territory’ for themselves or their gang. This is a risky business that can trigger violent retribution; the boundaries between territories are particularly fraught.

Some territories are delimited by obvious physical obstacles such as a freeway or other major road, railway tracks or the Los Angeles River. However, most boundaries are learnt through experience – often a deeply negative experience. Many boundaries are as subtle as two sides of a two-lane residential street, ‘our side’ and ‘their side’. Locals must therefore develop a mental map of where they can and cannot go without transgressing a fiercely defended yet invisible line.

In such turbulent spaces, residents need to make careful decisions every day in order to keep themselves safe. Sporting the ‘wrong’ colour or sports apparel, for instance, can have fatal consequences. A person affiliated with a gang may need to travel far to purchase groceries or petrol if these amenities are in neighbourhoods claimed by a rival. Their routes may also have to change on a regular basis, in accordance with shifting gang boundaries.

Consequently, what should be a short walk can become an intricate, circuitous journey through an invisible labyrinth. Even a person who has no gang affiliation at all may be caught in crossfire, with children as young as nine among those killed in shootings in recent years. Not without good reason, many residents are reluctant to speak to the police, lest their intervention become known to the gangs they fear. With all these risks involved, it is little wonder so few ‘outsiders’ ever see these places, unless they are passing over them on one of the city’s freeways. They may as well be on a different planet.

Befitting of a ‘gang capital’, Los Angeles is highly distinctive both in the pervasiveness of gang activity and in these groups’ diversity, rendering gang crime alarmingly normal. Conservatively – for various uncertainties and gaps exist in its crime statistics – more than 5,000 violent gang crimes, including homicides, felony assaults and rape, take place just in the City of Los Angeles every year. What’s more, this highly pressurised situation has been intensified by various incidents of police brutality against gang members as well as innocent bystanders. Racial profiling has further eroded confidence in law enforcement and teenagers are regularly arrested so that they can be fingerprinted and photographed for future reference. Even more scandalously, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department has a long history of employing ‘deputy gang’ members – that is, police officers who covertly engage in typical gang activities such as shootings, assaults and sexual harassment. For decades, new legislation and policies have been written and rewritten to tackle gang activity, and yet law enforcement still find themselves in a dilemma that is seemingly impossible to solve.

Perhaps no group is more acutely aware of the difficulties of distinguishing gang members and pursuing a life beyond the gangs than those who leave their peers to carve out a new lifestyle. This is not simply a matter of relinquishing membership. There have been cases where a former street gang member, with no intention to cause trouble, has been attacked and killed simply because they have been recognised as an old enemy of a local rival. Others continue to be approached and arrested by the police.

Former street gang members’ engagement with space hence tends to remain greatly shaped by their time in neighbourhoods that are violently delimited and contested in the manner of warfare. If they have the chance, many leave and never return. In their place, new gang members are socialised to preserve their groups’ boundaries through force, while compelling the authorities to play catch up. Whereas these lines are unlikely to appear on official maps, for local residents they have an impact that can be more substantial than any other kind of boundary within the city. Being able to identify and visualise boundaries can determine one’s behaviour – if not survival – in contentious places.

CONTINENTAL DRIFT

The Wallace Line

At their closest points, there are fewer than 40 kilometres between the Indonesian islands of Bali and Lombok. However, making the short journey from west to east can feel like travelling to a different continent. Whereas much of Bali is inundated with tourists visiting its beautiful beaches, rice paddies and volcanoes, Lombok is calmer, slower, less developed. Hinduism gives way to Islam, temples to mosques, suckling pig to beef satay. Particularly perceptive visitors may notice differences between the Balinese and Sasak languages. The waters may seem the same, but much else gives the impression of a stark juxtaposition. It is when the islands’ wildlife is considered that the contrast becomes particularly obvious.

In Bali, the fauna is ‘Asian’, including civets and woodpeckers, and historically tigers as well. In Lombok, the fauna is ‘Australian’, comprising porcupines, zebra finches and white cockatoos. How can just a hop, skip and a jump across the Lombok Strait reveal such a clear-cut difference? We have one of history’s most unfairly overlooked scientists to thank for the answer.

While Charles Darwin was developing his ideas on evolution based largely on his experiences in the Galápagos Islands, a younger, less renowned naturalist was drawing analogous conclusions more than 16,000 kilometres away. In many ways, Alfred Russel Wallace was the antithesis of his more illustrious contemporary. Whereas Darwin was born into a wealthy family and studied at both Edinburgh and Cambridge universities, Wallace dropped out of school aged 14. He was accustomed to being largely self-sufficient and in most of his endeavours was self-taught.

Wallace garnered important experience in the Amazon rainforest, where he produced a remarkably detailed and accurate map of the Rio Negro, but it is his pioneering work in the Malay archipelago for which he is today best known. From 1854 to 1862, he travelled extensively across this region, collecting more than 125,000 specimens. Through meticulously examining the archipelago’s fauna, he started to spot patterns that would help change our understanding of biology and geography forever.

Scientists were already aware that species vary geographically, but what particularly caught Wallace’s attention in SouthEast Asia was how even across short distances such as the Lombok Strait, there could be abrupt changes. Usually, sharp differences in plant and animal communities across space can be attributed to significant boundaries in the natural environment, such as mountain ranges and deserts, but between islands such as Borneo and Sulawesi there is just a short stretch of sea. Recognising this quirk, Wallace contended that there is an invisible line running north to south through the archipelago.

We now know that the ‘Wallace Line’, as it would come to be called, constitutes a complex series of tectonic plate boundaries. It would be another 100 years before the theory of plate tectonics would enjoy widespread scientific acceptance. Nevertheless, Wallace correctly identified that the water between the islands on either side of his line was much deeper than elsewhere in the region, thus preventing any animal species that could not swim or fly long distances from migrating. As a result, the species on either side would have evolved separately.

Wallace’s identification of a sharp divide in this part of the world has remained central to the discipline of biogeography and the concept of zoogeographic regions since the 19th century. More recently, the line has additionally been used to explain other differences, including with regard to human genetics, anthropology and linguistics.