The last serving member of 1953 Everest expedition and his glaciologist grandson discuss their fears for the beloved ‘Mother Goddess’

Report by Natalie Berry

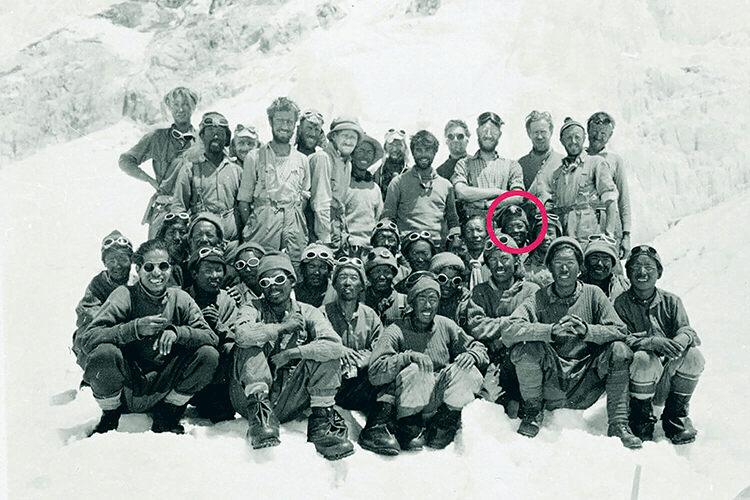

Kanchha Sherpa, 90, is the last surviving member of the 1953 expedition that reached the summit of Mount Everest. Aged 19 at the time, he carried equipment up to the South Col to aid Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s historic first ascent.

The oldest resident of Namche Bazaar, a staging point for Everest expeditions, Kanchha has witnessed the peaks darken from white to black. ‘There isn’t as much snowfall as in the past,’ he says. ‘The snow-capped mountains are not as snowy and I fear their essence and beauty are slowly diminishing.’

Before the first ascent, Sherpas were reluctant to climb their native mountains, deeming it disrespectful to the Tibetan Buddhist mountain gods. The Sherpas call Everest Chomolungma, ‘Mother Goddess of the World.’

Since 1953, Everest’s summit has been reached more than 11,000 times by more than 6,000 people.

‘With the boom of commercial mountaineering, I feel that people have forgotten the essence of the mountain deities,’ says Kanchha. ‘There are so many people climbing these mountains, living on the glaciers, and the waste they produce is polluting the sanctity of these sacred landforms.’

Kanchha’s grandson, Tenzing Chogyal Sherpa, 30, was moved by the laments of lost snow and ice. Today, he works as a glaciologist at the International Centre

for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), studying ice loss on Everest and across the Hindu Kush-Himalaya region. The latest studies by ICIMOD have warned that glaciers in the region could lose up to three-quarters of their volume by 2100, even if the world acts to limit global warming. These glaciers supply water to around two billion people downstream, who now live under increasing threat of avalanches, flooding, landslides and drought.

In 2019, Tenzing joined an expedition to assess climate change’s impact.

The team estimated that the South Col glacier – the world’s highest at 8,200 metres and the route most expeditions from the Nepalese side take to reach Everest’s summit – has lost 2,000 years of ice formation in just 30 years.

‘We estimate that over the last 30 years, the average temperature on Everest has risen at a rate of approximately 0.2–0.3°C per decade,’ says climate scientist Tom Matthews of King’s College, London, who has installed weather stations on the mountain. A phenomenon called elevation-dependent warming plays a role. ‘The higher the elevation, the higher the rate of warming,’ says Tenzing. Cold, dry air, 150 km/h winds and strong sunlight also increase sublimation – where snow and ice transform directly to vapour – exposing ice below.

Research suggests that warming might not drive gradual changes in mountain regions, but instead may be abrupt. ‘Whether it’s melting driven by ever-darkening surfaces absorbing ever-more sunshine, or the change from snow to rain, there are mechanisms that could trigger rapid transformations,’ explains Matthews.

In 2018, Tenzing followed in his grandfather’s footsteps on a research trip to Everest’s Khumbu glacier. The internal temperature measured 2°C warmer than the mean annual air temperature, despite below-zero air temperatures – showing how sensitive it has been to past warming.

‘There’s a lot of lag time in glaciers,’ says Tenzing. ‘Once the ice reaches the tipping point of 0°C, you have drastic melting.’

Consequently, the Khumbu glacier’s notorious icefall (5,486 metres), Everest’s most dangerous obstacle, is more dynamic. In 2014, 16 Sherpas were killed on the glacier when a number of seracs – unstable blocks of ice – tumbled down on them, dislodged after the early-morning sun had warmed the glacier. It’s the second-deadliest disaster in Everest’s history. The worst followed in 2015, with 22 fatalaties, when a number of avalanches struck the southern side of the mountain.

Since 1978, around 200 of the climbers who’ve reached Everest’s summit have done so without supplemental oxygen. A recent study published in iScience reports that higher air pressure due to rising temperatures has increased oxygen levels near the summit – a relief for oxygen-depleted climbers. But overall, climatic changes are having a more profound impact on the high Himalaya.

Scientists expect more frequent and intense melt periods, meaning that some sections could become trickier as negotiating exposed rock involves technical climbing and slower descents. ‘The Triangular Face on the Nepal side, between C4 and the Balcony, would be much slower to descend if snow cover was more patchy,’ says Matthews.

Snow-and ice-based climbing anchors will also require regular replacement to prevent fixed-line failure, while increased melting has prompted discussions of shifting South Base Camp 200–400 metres lower.

In the ’90s, commercial guiding on the South (Nepal) side boomed. Today, Base Camp bustles with helicopters and offers high-speed Wi-Fi. Clients pay an average of £45,000, and more than £70,000 for exclusive experiences, but budget guiding for about £25,000 is gaining traction.

In 2019, a shocking photo of a ‘traffic jam’ beneath the summit went viral. These queues increase the risk of oxygen deprivation in the ‘Death Zone’ above 8,000 metres and exposure to avalanches. This spring season, Nepal’s Ministry of Tourism issued a record 478 permits – generating US$5.8 million in revenue – resulting in more than 1,000 people on Everest’s flanks.

Overcrowding has caused a build-up of rubbish, abandoned equipment and human waste (and bodies) while also polluting the watershed with harmful synthetic ‘forever chemicals’. In 2019, the Nepalese government launched a campaign to clear more than 10,000 kilograms of rubbish.

More than 300 people have died on Everest since 1953. The spring season this year was the deadliest yet, with a record death toll of 17 – well above the average of four.

Deteriorating conditions and safety concerns have caused some guiding companies to move operations to the quieter north side in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, with its better infrastructure, good road access and far stricter and more rigorously policed regulations.

Adrian Ballinger of Alpenglow Expeditions shifted north following the avalanche disaster of 2015. ‘With the current lack of regulation of Everest in Nepal, we believe it is impossible to safely and ethically run an expedition to the south side year after year,’ he says. The problem is not necessarily the number of permits being issued, Ballinger explains, but rather climbers who are ill-equipped for the Khumbu Icefall and put lives at risk.

‘The dramatic increase in numbers, specifically inexperienced climbers led by inexperienced guide companies, has created a tinderbox where big accidents are inevitable when they could be avoidable,’ he says. ‘All we can do is advocate for the increased regulation of the mountaineering industry in Nepal.’

In recent years, the Nepalese authorities have debated introducing a permit quota and minimum-competency regulations to reduce risks and environmental impacts, but they have yet to implement tighter controls.

Accidents related to climate change and overcrowding disproportionately affect local Sherpa porters, who undertake dangerous work and are often involved in rescue operations. While some Sherpas are leading personal climbs and founding expedition companies, many now work elsewhere in Nepal’s tourism industry.

In April, three Sherpas died in an avalanche on the Khumbu Icefall. ‘We need to look through another lens at the dark side of mountaineering,’ Tenzing says. ‘It’s like going to a battlefield.’

Scientists predict that the South Col glacier may disappear by 2050, meaning that Everest’s high reaches could be bare, black bedrock by the time of centenary celebrations.‘The cause of climate change is global, but the effects are local,’ says Tenzing. ‘This region is the perfect example of its symptoms. Climate change is exposing mountain fragility and now they are not as strong as we thought.’

As Kanchha joined 70th anniversary events this May and reflected on his historic role, Tenzing continued his field work. ‘My grandfather is the past of the Everest region,’ he says. ‘And I plan to be the future and continue his legacy in preserving Sherpa culture, the environment and its people.’