In Abyei, a land sandwiched between Sudan and South Sudan, but belonging to neither, staff from Médecins Sans Frontières are working hard to bring life-saving treatment to desperate communities

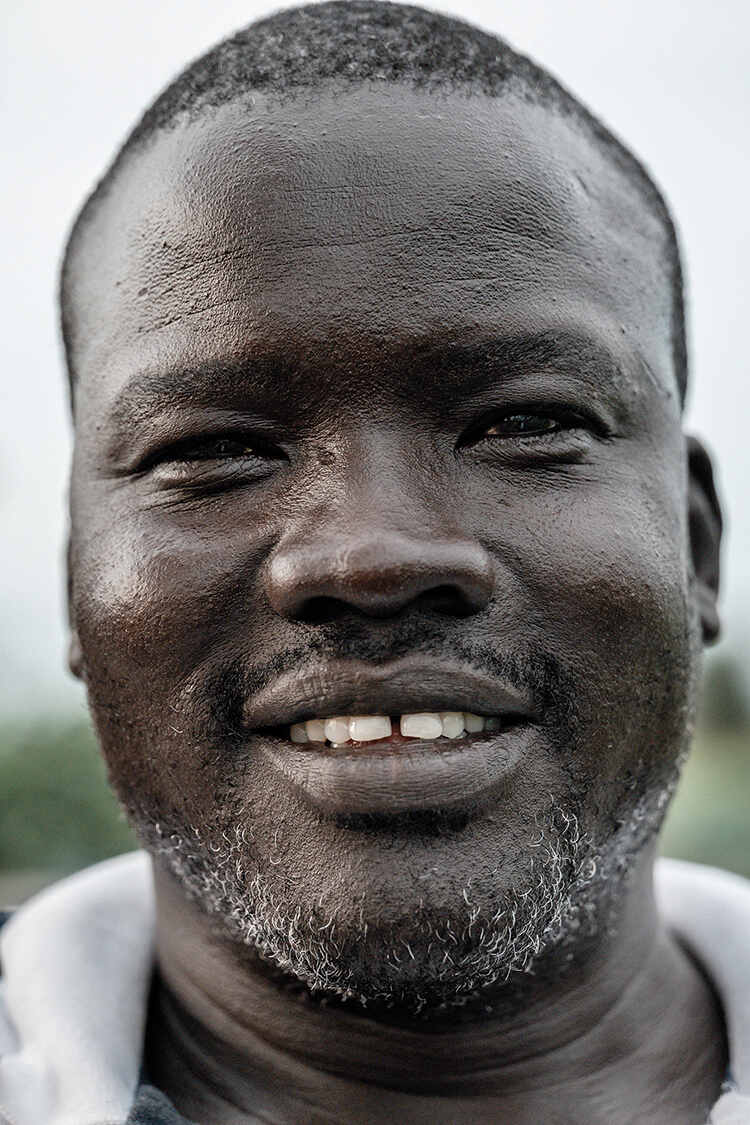

Report by , Images by Sean Sutton

A devastating war to the north; the poorest country in the world to the south; and in the middle, a forgotten territory where tribal warfare, natural disasters and a decline in international aid contribute to a desperate situation in which aid workers and medics struggle on.

This is Abyei, a disputed region of around 10,000 square kilometres, home to 143,000 people and tens of thousands of the internally displaced. Accorded ‘special administrative status’ at the end of the Second Sudanese War in 2004, it now limps on, neither here nor there, belonging to no-one.

It wasn’t meant to be this way. Abyei was due to have a referendum in 2011 on whether its inhabitants wished to join South Sudan. The idea was for it to take place simultaneously with the wider referendum that saw the creation of South Sudan as a sovereign nation. However, while the latter went ahead, and South Sudan was born, Abyei’s referendum ran aground due to a disagreement over voter eligibility. Instead of having the opportunity to vote, Abyei was invaded by the Sudanese Armed Forces in May 2011. They still maintain a presence in the north of Abyei around the area’s sole oil field, Diffra, despite repeated calls by the UN Security Council for the force to withdraw.

Today, amid the impasse, a dizzying array of problems besets the land and its people. The Ngok Dinka, one of the tribal peoples who live in the region, face disputes on both sides.

To the north are tensions with the Misseryia, an Arab nomadic tribe that migrates seasonally into Abyei from Sudan. To the south, communities are still reeling from a surge of inter-communal violence that broke out in 2022 with the Twic Dinka, another tribe from the state of Warrap in South Sudan. Fighting between the two groups focused on the border town of Agok and the ownership of an important market, displacing some 70,000 people. The town now lies deserted, with empty and broken dwellings dotting an overgrown landscape.

Many of the displaced people now live in camps around the town of Abyei to the north of Agok; others fled into South Sudan. While there have been moves to calm the situation, with UNISFA (the United Nations Interim Security Force for Abyei) congratulating the two sides on peace talks held in April, recent reports suggest that the violence hasn’t ended.

UN armoured vehicles dot the dangerous roads between villages. Meanwhile, young men wielding AK-47s move past weathered signs declaring that ‘this is a demilitarised zone’. Suspected Twic youth attacked a market in Abyei town on 29 September, killing 11 people and wounding 16, just one kilometre from UNISFA’s main base.

The fighting has exacerbated an already perilous situation. In one camp for internally displaced people in Abyei town, around 2,000 families now reside in makeshift shelters, cobbled together from sticks, leaves and cloth. They offer little respite from the harsh conditions, while food shortages persist and diseases such as malaria and measles are prevalent. Some fled here from the fighting in Agok; others came to escape flooding in neighbouring Unity State. Refugees from the war in Sudan are also entering the region in large numbers.

‘The area is very overcrowded and people are still arriving,’ says Akur, a single mother with seven children. ‘It was okay at first, but since April we have been suffering more. New arrivals don’t get ration tokens; they can’t get help with shelter and food. So, we take care of them even though we don’t have enough ourselves. This is additional pressure we can’t live with, but people can’t eat alone; we should eat together. We have to share what little we have.’

The situation is similarly desperate in the camps in South Sudan. Some of the people who fled Agok ended up in Gongoi IDP camp, where more than 6,000 people now reside. ‘Sometimes we can find food, sometimes not. We are often hungry,’ says Achuei, a mother living in the camp. ‘Life is very hard for us: our shelter leaks, our mosquito nets are torn. We need help.’

Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders; MSF) is the main form of help in the region. The privately funded medical aid organisation has been operating in Abyei since 1997. Having had to abandon the original MSF hospital in Agok following the 2022 fighting, the organisation now supports two hospitals: one in Abyei town and one in Mayen Abun in Twic county, South Sudan.

The challenges in both locations are numerous and heavy. Travel between the two locations has to take place by plane despite the short distance – the roads are simply too dangerous. On top of logistical problems, many individual staff members have faced, or are still facing, their own personal struggles, either because they come from the region themselves or because they hail from other nations caught up in conflict.

However, if there’s hope to be found in Abyei and the surrounding towns, it surely lies among these medical staff, doing all they can to treat and protect a largely forgotten people, and in the work being done to train local people and community volunteers. In a situation that feels hopeless, these are people with a remarkably enduring hope.

‘I love my job. I help people to have a smile on their face. The challenge, really, is being away from my family, especially now, with prospects of conflict happening in my country,’ says Awa Abdou, a nurse activity manager with MSF in Abyei. Born in Niger, she has been working with MSF since 2013 across various countries. ‘The work here is amazing. I really appreciate the programme we are working on. We save so many lives. We stop people getting seriously ill from malaria and diarrhoea. We are here to save lives and that’s what we are doing.’

Nur Mawien is an MSF nursing team supervisor at the Ameth Bek Hospital in Abyei. ‘Our work here is integrated with the Ministry of Health and we mix MSF staff with government staff at all levels to help with capacity building so that in time, we can hand it over,’ he says. Born in the north of Abyei, near the oil field, he moved to Sudan in 1986 as a refugee from the civil war taking place at that time, but has now returned to his homeland to work at the hospital.

‘It is challenging because we have to train them [local staff] through MSF guidelines that are different to the government guidelines. Also there can be language barriers and there are different levels of education. But we must keep working at it, we must keep trying – it’s important. Most of them are open minded and want to learn, so it is working, and they have improved a lot. There is a big difference compared to before and they really appreciate it. I am happy, they are confident to work independently and communicate well with us.’

As the rainy season takes hold, malaria is a big concern for MSF. In response, it’s running community-outreach programmes in which local volunteers are trained to test for malaria, understand the warning signs and provide life-saving drugs. These kinds of outposts are crucial because many people are reluctant to make the arduous journey to hospital and can end up doing so far too late. Knowing when to act can be lifesaving. ‘My team are very good at what they do,’ says Awa, who leads these programmes. ‘They are very motivated to help the community.’

Providing this service is hard work, however. Villages and camps are spread out, the roads are bad and the weather worse. ‘Sometimes we walk for hours in difficult conditions, like today in the flood. We have to work through the seasons and access cut-off communities. The more cut off they are, the more they need us,’ says Awa.

Staff here are used to these conditions, displaying as much resolve as the people they work to help. Abdulrahman Khaleel, the MSF project coordinator in Abyei, is no stranger to resilience, but even he has been shocked by what he’s seen in Abyei. A former civil engineer, he joined MSF as a logistics assistant in 2017 and worked his way up to become a field coordinator before becoming a project coordinator in 2022. Born in Iraq, he lived through the war in Mosul.

‘Before coming here, I thought Iraqis were strong and resilient, but I have changed my mind,’ he says. ‘In one night, a whole community [in Abyei] can up sticks and stay out in the open, in storms, in rain and still show up for work the next day. I was amazed. If you ask someone in Abyei about their life, their difficulties, they will give you many stories. Everyone has two or three unimaginable, traumatising stories of suffering and yet they have found a way to move on in life and stay sane. In other parts of the world everyone would be suffering from psychological issues.’

One of the things Khaleel has enjoyed most since starting work in Abyei is setting up an MSF football team. In June, the organisation hosted a multi-day tournament in which 12 local teams played alongside the MSF team – a remarkable feat in a region beset with inter-communal violence. ‘When I was a kid, my life was about football; my dream was to have a ball and play with it,’ he says. ‘It was a difficult time; it was a time of war in Mosul. I felt empty. I felt I had no future. I think some people here feel the same as I did when I was 14.’

This kind of community activity complements MSF’s focus on diversity, equity and inclusion within its overall project. The organisation notes that this focus has led to a positive shift in gender roles (with female drivers and male midwives now operating in South Sudan) and to the promotion of locally hired staff to managerial positions through training and development programmes.

All of this work looks forward to a day when MSF won’t be needed in the region – when local medical staff can take over and the infrastructure exists to support communities. However, for the time being, this is a dream that feels a very long way off. Despite MSF’s work, the humanitarian crisis in Abyei and in South Sudan shows little sign of improving. Hunger, disease and violence are daily occurrences. And, with the war in Sudan ongoing, displaced people are likely to keep arriving, adding to the burden. More than anything, MSF staff and the people caught up in these conflicts want the world to notice.

‘I have enjoyed being here – there is never a dull moment,’ says Khaleel. ‘As a human, this kind of experience will make you appreciate what you have and realise the difficulties some have in this universe. It will open your eyes to a lot of things.’ But even while pointing to the highly motivated and driven workers around him, he sees no obvious solution to the problems that beset Abyei. ‘There are a lot of issues here. UNISFA are blocking the conflict, trying to stop violence from happening, but they are not trying to solve the problems. The motives for conflict are still there. I wonder if anyone is looking at ways to find peace, to solve the issues.’ l