Louise Kenward draws together the stories of people with disabilities and their love for nature in vital and timely read

By Olivia Edward

Disabled writer Eli Clare often drops to his hands and knees when out traversing a natural landscape. He relishes being an ‘inchworm humping along the ground’, spots of grey lichen prickling his hands.

Yes, in mud and snow, it ‘can be a messy affair’, he admits – hands get scratched and shoulders get sore – but ‘even so, I adore scooting’, he writes. ‘It slows me down, distance no longer measured in miles but rather in yards. I creep, inch and linger.’

He only wishes there wasn’t such a taboo around the ‘sliding, scooting, crawling, crab-walking’ that bring her into an intimate relationship with the earth, and longs for the day when disabled people can make their way across the land in any way they find most comfortable without garnering undue attention or judgment from others.

His is just one of a series of sweepingly different testimonies gathered together in this pioneering collection of nature writing by people living with disability and chronic illness.

The works are varied but cohere together in their authors’ unwavering dedication to the honest conveyance of their unique and particular experiences of the world. They include tales about everything from raves on wild Welsh moorlands to the indoor weather experiments a disabled artist creates for her housebound cats.

There’s a suggestion from some that their conditions have bestowed upon them a unique understanding of the more-than-human world. ‘The disabled body is a profoundly natural body,’ writes Jamie Hale. And yet there’s a cruel dual edge to the sensation, given the ‘pernicious ways in which disabled people are excluded from nature. I experience the outside world as a contested space that makes no room for my physically impaired body.’

Khairani Barokka agrees. ‘I do not want to be undisabled at this point; it has taught me too much, given me too much. What I want is not to suffer as a disabled person.’

Beset at times by the very nature of their own bodies, others call out the shocking dismissals they receive from medical institutions. Kerri Andrews being told repeatedly that there was nothing wrong with her while she was actually experiencing the debilitating symptoms of haemochromatosis, a genetic condition that causes layers of iron to be laid down in cells and organs (making her beloved Munro-climbing rather difficult).

Endometriosis sufferer Rowan Jaines also questions the ‘phallus logic’ that has constructed a world in which her painful experience is somehow misconstrued by medical professionals as a malady of character.

While Alec Finlay, who writes with thrilling acuity about his experiences of living a wilded life with ME, poses the question of ‘how to represent pain without being hemmed in by shame.’

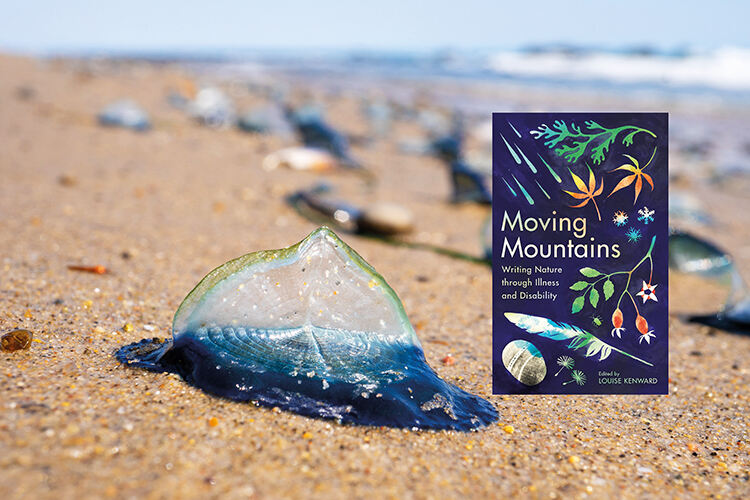

Prickling luminously in nearly all of the stories are moments of breathtaking beauty: Sally Huband, who struggles with a condition that causes chronic pain in her joints, leaving her sleepless and sore, savors her trips to the beach on the Hebridean island where she lives. There, one day, she finds ‘a mass of tiny violet-blue tentacles’. They are by-the-wind sailors, like mini Portuguese-men-of-war, their bodies the length of her thumb. She sticks one, ‘viscous tentacles down, to the skin on the back of my hand. It holds fast. I gather more until both hands are gloved in violet-blue. I’ve read that they do not sting but find that they do, and softly. They reach down through the surface of my skin and turn pain into something more diffuse, beautiful and worn.’

Kenward writes in her introduction that she was motivated, in part, to draw this collection together because she saw that where disability stories are reported in the media, they are often in the guise of overcoming disability or illness, as if it was simply a temporary inconvenience, whereas, in truth, for many, the opposite is the case, and often people are having to come to terms with the fact that they are facing a lifetime of disability or illness. And, besides, as contributor Isobel Anderson notes: ‘We are all temporarily able.’

Nature can ameliorate. ‘Sitting in the woods or at the beach, I glimpse a world that relishes crookedness, wholeness and brokenness, an explosion of sizes and shapes,’ writes Eli Clare. ‘In the more-than-human world my shaky asymmetrical body is just one among many. I find spaces and relationships neither saturated with nor defined by ableism.’

Together the works cumulate into a mass unshackling – a refusal to be defined by currently existing cultural norms. And, alongside that, they contribute to the slow, steady work of dismantling an entire way of seeing that has erroneously established a hierarchy of bodies.

This is a book the nature writing genre has been waiting for. There are lessons here for everyone. A vital, urgent and timely read.