Manifesta, an arts festival in Kosovo, tackles the nation’s turbulent past amid rising tensions with neighbouring Serbia

By Tim Brinkhof

On the final day of my brief stay in Pristina, the capital city of the Republic of Kosovo, some fellow travellers urged me to check out an arts festival called Manifesta. This nomadic biennial, founded by Dutch art historian Hedwig Fijen, is known for setting up shop in locations where the political climate is anything but stable. In 2006, for instance, Manifesta was supposed to come to Cyprus, but plans fell through following a disagreement between the island’s Greek and Turkish inhabitants. And in 2014, the festival arrived at Saint Petersburg, Russia, just months after Vladimir Putin moved his soldiers into Crimea and signed a law banning gay ‘propaganda’.

Pristina makes for an equally tumultuous backdrop. Preparations for Manifesta were well underway when Putin – unsatisfied with his previous annexation –

launched an invasion that’s threatening not just Ukraine but all of Eastern Europe. Kosovo’s already weak economy has grown even weaker, while its age-old enemy, the Kremlin-backed and Kremlin-backing government of Serbia, is being emboldened by nationalist fantasies of its own. Emulating Russia, Serbia didn’t recognise Kosovo as a sovereign nation when it declared itself one in 2008, and continues to deny its independence to this day.

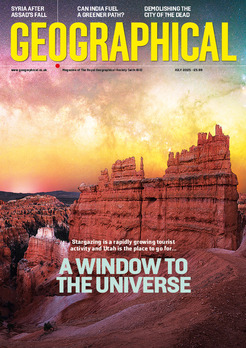

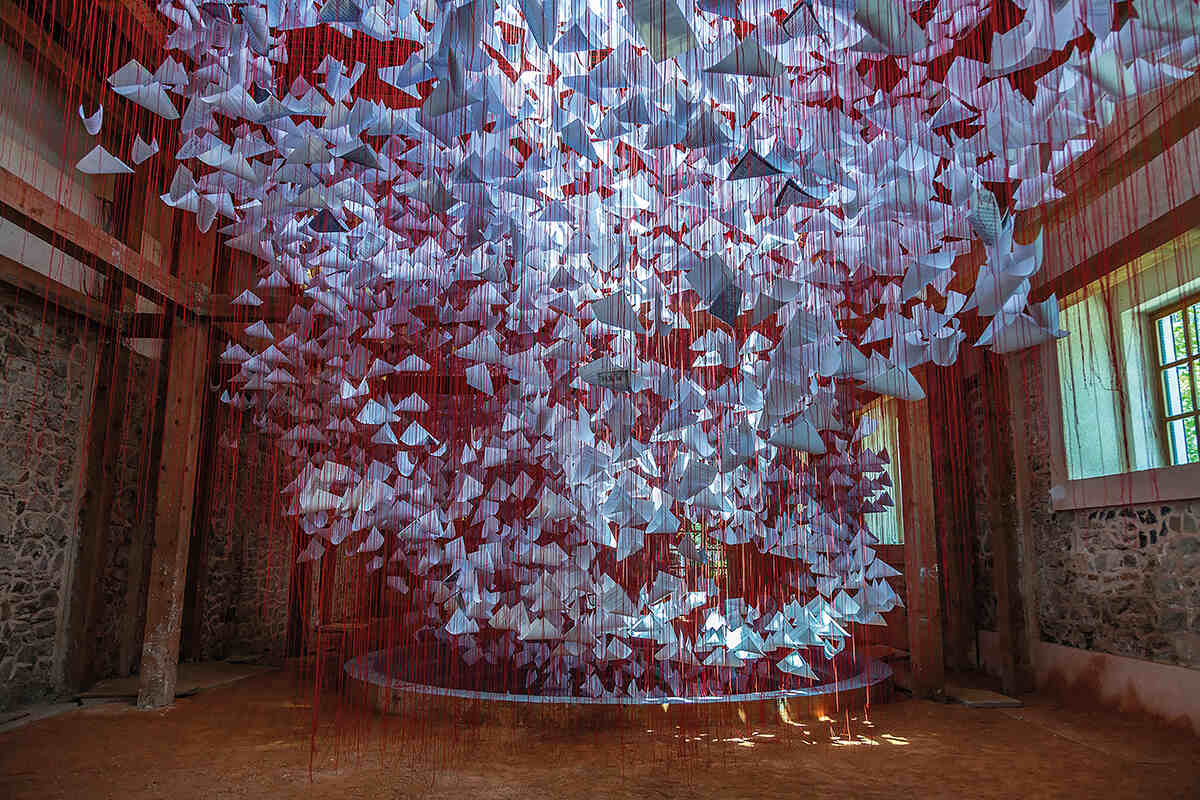

Kosovo’s tragic past and uncertain future add weight to Manifesta’s art exhibits. Donjetë Murati, a programming coordinator, says that one of the goals of the festival is to ‘challenge dominant narratives and inspire alternatives to a world where violence and war take place’. Take, for example, ‘Ring the Bells my land’ – a futuristic, post-apocalyptic installation by the Prizren-based artist Doruntina Kastrati located inside Pristina’s dilapidated Grand Hotel. Here, visitors are encouraged not only to observe the installation, but to walk on top of it, further pulverising heaps of red brick that are meant to represent the surface of a colonised Mars. The message is subtle yet obvious: the creation of art – like the recording of history – ought to be a collaborative process. This is hammered home more clearly at another building occupied by Manifesta: the Centre for Narrative Practice. Inside this quaint little townhouse, tucked away between office buildings and kebab shops, various objects recount a collective history of Kosovo. Family photographs, knickknacks and a box of discontinued Soviet cereal, paint a picture of the past that’s more trustworthy – as well as objective – than any individual historian (or politician) could ever produce.

Constructed during the 1930s, the Centre for Narrative Practice was once used as a municipal library before falling into disrepair and, ultimately, disuse. Thanks to Manifesta, however, the city of Pristina has been able to raise the funds necessary to renovate the townhouse and its private garden, which now doubles as an outdoor workspace, with music and food trucks. Murati tells me that the renewed centre contains a reference library, a children’s library, historical archives, a podcast studio and a screening space – facilities, she says, that will remain available to local residents long after Manifesta has left the country.

The Centre for Narrative Practice is but one of many abandoned buildings in Pristina that Manifesta is helping to restore. In the Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad, photographer Atdhe Mulla has published pictures of students (paid a decent salary according to one of them) painting the outside of an old factory that, prior to the festival, was used as an unregulated garbage dump. Pristina’s Grand Hotel, built on the orders of Yugoslav dictator Josip Tito to accommodate ambassadors and other diplomats, businessmen and other guests of distinction, is also resuming its role as a hub for high culture in Kosovo.

For readers in the USA and Western Europe, where urban environments are regenerated all the time, initiatives such as these may not sound particularly noteworthy, yet they acquire special significance when viewed from the perspective of Balkan history. That history has been described in all its sad detail by Peter Lippman, a Seattle-based carpenter turned journalist and human rights advocate, and the author of Surviving the Peace: The Struggle for Postwar Recovery in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Lipmann spent years campaigning in Bosnia and Kosovo – countries where people, and public spaces, suffered heavily under Serbian repression.

Although the enmity between Serbians and Kosovo’s ethnic-Albanian population goes back centuries, Lippman believes that the present conflict began during the 1980s, when Serbian president Slobodan Milošević revoked the autonomy that Kosovo had gained under Tito and his immediate successors. In Pristina, professors who refused to teach Serbian curricula were fired on the spot. Kicked out of their own institutions, they taught classes in basements and backrooms. In an article for the Seattle Times, Lippman recalls attending an advanced-English course inside an empty, unheated store where students used boxes as chairs and tables.

In healthcare, things were even worse. Doctors and nurses were told to turn in their scrubs, sometimes while they were in the middle of operating on someone. A parallel medical system was created, but it was too poorly equipped to take care of Kosovo’s ailing population. At the Mother Teresa Clinic, the only free clandestine clinic in the region, pregnant women had to share beds while giving birth for lack of space. Once their babies had been delivered, they were given two hours to leave the facility. In response to these conditions, more and more mothers were forced to go into labour at home, causing infant mortality rates to skyrocket.

Keeping these historical horror stories in mind, one can see clearly that Manifesta employees are doing more than cleaning up garbage dumps and building podcast studios. They are also helping to rebuild the infrastructure that Serbia dismantled for the purpose of undermining Kosovo’s economy and human development. With public places such as the Centre for Narrative Practice back in use, citizens of Pristina no longer have to meet in each other’s private residences to look back on the past and plan their futures. Topics such as political repression, civil rights and war crimes can now be discussed openly, freely and defiantly. At least, that’s the idea.

Unfortunately, Manifesta’s impact on Pristina has been overshadowed by news coverage of an unnerving confrontation between the governments of Kosovo and Serbia. This confrontation began a little over a year ago, when Kosovo’s prime minister, Albin Kurti, announced that ethnic Serbs living in the country would have to start fitting their vehicles with Kosovar, as opposed to Serbian, number plates. The Serbs, provoked by their brethren on the other side of the border, responded by organising protests and roadblocks. For months, the world has been waiting to see what will happen once the new rule goes into effect.

An initial deadline was set for 1 September 2022. However, pressure from Kosovo’s Western allies persuaded Kurti to wait until the two countries could reach an agreement with which both can live. Diplomatic meetings, facilitated by European emissaries and monitored by NATO peacekeepers, took place throughout August. But while Serbia and Kosovo have agreed to waive certain entry and exit requirements for travellers heading in either direction, and various government officials, including Serbian prime minister Ana Brnabić have expressed a desire to see their relationship normalised, tensions have yet to defuse.

And they won’t anytime soon. The countries are arguing about much more than number plates. In Lippman’s words, it’s simply another ‘manifestation of Kosovo trying to assert its sovereignty and Serbia trying to deny it’. A similar scenario played out last year when Serbia placed special police units along the border. Tomorrow, Lippman adds, discussions may revolve around criminal justice (Serbia and Kosovo rarely cooperate in the search for missing persons) or around the Community of Serb Municipalities, an as-yet unsuccessful campaign to allow areas in Kosovo with majority Serb populations to form a self-governing federation.

Could one of these scenarios lead to war in the Balkans? It’s possible, but unlikely. Kosovo and Serbia have, of course, fought before, during the late 1990s. The conflict, which ended soon after NATO began bombing the Serbian city of Novi Sad, left a bitter taste in the mouths of both sides – especially Serbia. Today, war is kept off the table by the involvement of foreign powers mightier and wealthier than Serbia and Kosovo combined. Under their auspices, leaders regularly meet in Brussels to air their grievances, and although Lippman thinks these visits are a diplomatic charade, they have, for now, contributed to keeping the peace.

Still, those who travel through the region today sense danger in the air. Aleksandar Vučić, Serbia’s current president, has declared time and time again that he will never recognise Kosovo. In light of recent events, his defence ministry has been carrying out training to ‘maintain a high degree of combat readiness’. And such inflammatory language isn’t restricted to political press briefings; while in Tirana, I ran into a Dutch backpacker who had just came from Belgrade. He told me how, at a local bar, he met a group of teenagers who said that they would ‘die for their country’, and who pressured him into saying, out loud, that ‘Kosovo is part of Serbia!’

Far more probable than war is the prospect of Russia exploiting political instability to extend its sphere of influence in southeastern Europe. Not only has Putin rejected Kosovo’s claim to sovereignty, but he has also provided Serbia with military training and equipment. Elsewhere, in Bosnia, the Kremlin threatened to ‘react’ should the increasingly westward-leaning country decide to join NATO. In this sense, conflicts in the Balkans are about much, much more than local rivalries; the region is rapidly becoming one of several battlegrounds on which Western powers will be waging their new proxy war against Russia.

The great tragedy of it all is that Kosovo – in a turn of events that’s somewhat rare in this part of the world – has acquired a remarkably stable and honest regime. Where many neighboring countries are ruled by personality-based parties whose members act more like common criminals than government officials, Kosovo’s Kurti is part of a true grassroots movement. This movement, called Lëvizja Vetëvendosje (the Self-determination Movement), gained followers not through force or fearmongering, but through peaceful demonstrations and educational events. Its delegates, Lippman says, actually represent their constituents.

The origins of Lëvizja Vetëvendosje can be traced back to the final years of the previous century, when students, tired of congregating in basements and backrooms, took to the streets. They wanted their classrooms back and they wanted to be taught in Albanian, not Serbian. Gradually, spontaneous and disjointed protests coalesced into a single organisation that called for the boycott of Serbian goods, the release of political prisoners locked up across the border, the prosecution of war criminals and other things that – to quote Lippman one last time – ‘matter to ordinary people’.

Both Kurti and Kosovo’s young, female president, Vjosa Osmani-Sadriu, enjoy widespread support due to their unwillingness to compromise with Serbia. This is in stark contrast to Osmani-Sadriu’s predecessor, Hashim Thaçi, who, in 2018, was talking to Vučić about redrawing the border so that Kosovo’s ethnic Serb municipalities would once again fall under Serbian jurisdiction. Thaçi left office before his plan could proceed – a good thing, according to political analysts, as ceding even the smallest portion of Kosovo’s hard-won territory could leave the republic vulnerable to other secessions and perhaps even occupation.

Although the recent victories of Lëvizja Vetëvendosje inspire hope for a better future, the overall situation in Kosovo still looks rather grim. Reports from the European Commission show that the republic’s judicial system is dubious, its law enforcement unreliable. For every Kurti or Osmani-Sadriu, there’s a powerful person who only looks out for themselves.

But worse than Kosovo’s corruption is its poverty. Around 18 per cent of the population lives below the poverty line, with five per cent below the extreme poverty line. In 2020, the unemployment rate reached 25.8 per cent, the highest of all the candidates competing for EU membership.

Poverty goes hand in hand with another serious problem: brain drain. The Kosovo Agency of Statistics estimates that more than 220,000 people left the country over the past decade, a sizable portion of its population of 1.8 million. Many of these emigrees are young people looking to try their luck abroad – understandable considering that, at home, one in every two college graduates can’t find a job. Those who find work don’t fare much better. A journalism major from the University of Pristina, who moved to Zagreb to work in construction years ago, says that most employers in Kosovo make you work long hours for little money, without offering insurance benefits.

And yet there is more to this story. Walking through Pristina, I ran into quite a few young professionals who could leave but choose not to. One such was Manifesta programming coordinator Donjetë Murati, who studied art and activism in New York. I met her in the garden of the Centre for Narrative Practice, where she sat with her laptop. Although she could have stayed in the USA – a country in which many emigrees aspire to end up – she made a conscious decision to return to Kosovo because, despite everything that’s happened in the past, she is deeply in love with her country and believes that she can do some truly important and meaningful work here. I don’t doubt it.