The world’s largest inland body of water, the Caspian Sea, faces water level decline, threatening ecosystems, economies & regional stability

By Clément Girardot, photographs by Julien Pebrel

Amid the ongoing Ukraine conflict, the Caspian Sea has gained significance for energy and trade. It’s crossed on the north–south axis between Russia and Iran and the east–west corridor that connects China and Central Asia to the west.

In November, the Caspian Sea will be even more in the spotlight as Baku is set to host COP29, the annual UN conference dedicated to climate change.

In the Azerbaijani capital, world leaders and activists will discuss a new agreement. Next to them, an unprecedented ecological crisis is unfolding, visible through the sharp decline of the sea level.

Enjoying this article? Browse through our related reads…

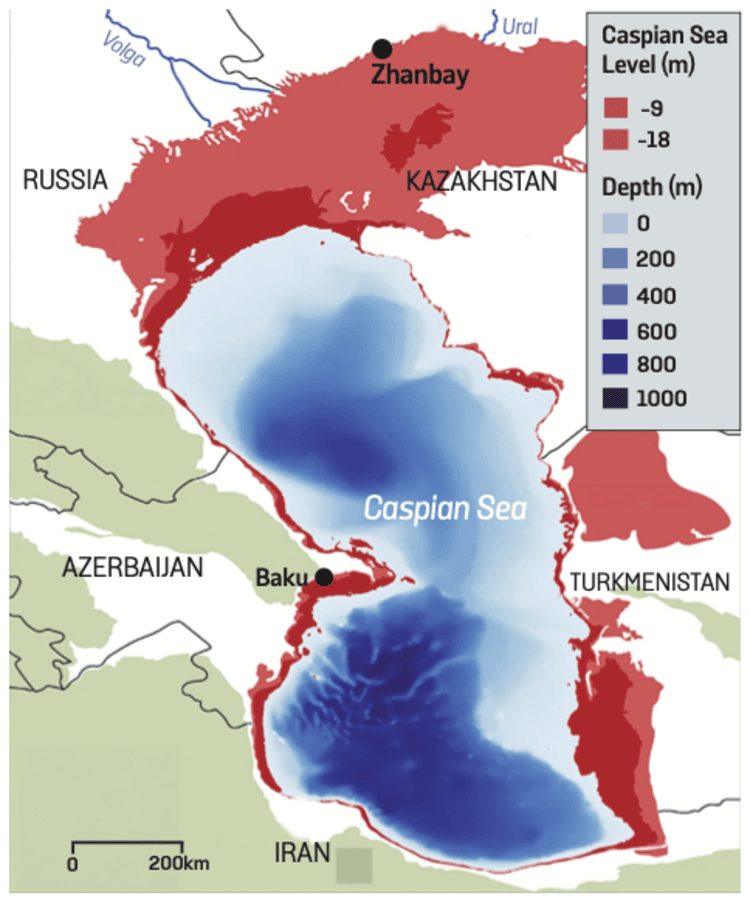

The Caspian Sea’s water level has dropped two metres since the mid-1990s, particularly affecting the shallower northern basin, which could face near-total drying

by the century’s end. Coastlines have shifted up to 50 kilometres in some areas, affecting human and economic activities, including the oil industry. Among the five Caspian nations, Kazakhstan is so far the most affected.

‘The climate here is tough, with very little rainfall, and the wind is relentless,’ says Amanjai Ibatulo, who lives in a large white house on the edge of Zhanbay, a small town on the northern shore of the Caspian Sea in Kazakhstan. Twenty years ago, the coast was just two kilometres from his home, but today it’s more than 20 kilometres away. The sea is now at the end of a sandy track that crosses an arid, flat steppe.

Nostalgic for the USSR, this 70-year-old former sports teacher fondly recalls a time when unemployment didn’t exist and the sea was abundant with fish. He becomes even more animated when talking about the fishing trips he enjoyed with friends: ‘From the 1980s to the 2000s, you didn’t even need a boat to catch fish. We would just take a volleyball net, walk out a bit, and come back with two or three sturgeons in half an hour.’

The sturgeon, with its sleek silhouette, is the symbol of Zhanbay. A statue of the fish sits on a pedestal in the town centre. Locals savour its meat, making a variant of Kazakhstan’s national dish, beshbarmak, which traditionally includes noodles, potatoes, onions and boiled horse and lamb meat.

The largest of the sturgeons, the beluga, can grow up to seven metres in length and is highly sought after for its caviar, which can sell for thousands of pounds per kilogram. Amanjai and other men in the village have countless stories of extraordinary catches from the past.

‘Now it’s illegal to fish for sturgeon, and the fines are steep. We used to eat it all the time, and we miss it,’ says Didar Yesmoukhanov, the mayor of Zhanbay, sitting in

the local administration building. A panel in the room traces the village’s history; it was founded in the 1930s alongside a Soviet fishery collective that finally closed down in the 1990s.

Due to the low living standards, many in Zhanbay continue to fish, despite declining catches and the restrictions. The official fishing season, which focuses on carp, lasts a few months in spring and autumn.

The six species of sturgeon in the Caspian Sea are all at risk of extinction, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Overfishing, poaching and pollution are the primary causes, but another, less-discussed factor is the rapid decline in the Caspian Sea’s water level, which is also endangering an entire coastal and maritime ecosystem.

Put your geography knowledge to the test and win a prize…

It’s threatening shallow-water habitats that support not only fish but also migratory birds and endemic Caspian seals, which are vital to the region’s biodiversity. In Russia, the catch of bream has decreased tenfold over the past 85 years, while the roach population has declined by a staggering 100-fold.

Similarly, in Kazakhstan, species such as catfish and pike are disappearing, prompting authorities to implement a temporary fishing ban in an effort to preserve the remaining populations.

In Zhanbay, the water level is dropping each year by 20–30 centimetres, causing the shoreline to recede by two to three kilometres. This retreat caught local authorities off guard. ‘We wanted to dig a channel for fishing boats, but the sea withdrew too quickly,’ laments Mayor Yesmoukhanov.

The issue has reached the highest levels of Kazakh politics. In a 2022 speech, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev called the situation ‘severe’ and initiated the creation of a research institute dedicated to studying the Caspian Sea.

The project was officially approved last January, but the research centre has yet to get going.

Scientists are increasingly pessimistic about the Caspian Sea’s future. In 2020, two German and one Dutch researchers published an article in Communications Earth & Environment warning the public of the potential for a significant drop in the Caspian’s water level. They predicted a decrease of nine to 18 metres by the end of the century, which could lead to the complete disappearance of the northern basin.

Climate change, they argued, is the main culprit, with increased evaporation not being offset by increased rainfall or higher river flows.

The sea currently covers roughly 371,000 square kilometres and stretches nearly 1,200 kilometres from Kazakhstan in the north to Iran in the south. In the past, its water levels have oscillated, but this century has seen a steady and disturbing decline.

It contains a massive 78,200 cubic kilometres volume of slightly salty water – more than three times the total of all five of North America’s Great Lakes combined. Nearly 80 per cent of the inflow is from the Volga River, Europe’s longest at 3,690 kilometres, which is now hindered by a series of huge dams and reservoirs built during the Soviet period.

The Volga is essential for Russian energy production, agriculture, and the supply of water to Moscow and other major cities.

‘The river has become polluted, silted up and overwhelmed by invasive species. The water flows at a tenth of the speed it did before the dams were constructed,’ noted Russian science journalist Olga Dobrovidova in an article published by MIT Technology Review in December 2020.

CASPCOM (the transnational committee in charge of hydro-meteorology in the Caspian zone), in its latest report in May 2024, cites the drop in the Volga’s contribution from 212 cubic kilometres for 2022 to 207 cubic kilometres for 2023, as ‘the main reason for the continued fall in sea level’.

Most of the Volga delta is in Russia, but a small part lies in Kazakhstan. This wetland has been a haven for birds and fish. ‘The water level has been dropping for five years now, and mud is accumulating in the canals,’ says Satti Boldi, an oil industry worker who resides in Kurmangazy, the main Kazakh town in the Volga delta. This increased aridity is fuelling a rise in wildfires in both the Russian and Kazakh parts of the delta.

In Russia, the area affected by catastrophic fires in the delta grew by 34 per cent between 2010 and 2020.

In the early 1990s, some families were relocated from Zhanbay to the village of Jana Zhanbay (‘New Zhanbay’), 25 kilometres west along the railway to Russia. The sea was rising from the 1970s until the mid-1990s, and the authorities were concerned that Zhanbay could be flooded. Despite the subsequent fall of the sea level, new residents remained in Jana Zhanbay and now live mainly by raising camels on the edge of a desert region they nicknamed Dubai.

‘We’re sad that the sea is retreating, and because of this, the wind carries salty dust that is harmful to animals,’ says 68-year-old resident Ibragim Bozakhaev, who grows apricot trees in his garden, one of the few fruit trees that can withstand the arid climate.

For those living near the coast, the sea’s retreat is also a public health concern.

‘We have frequent sandstorms in summer. Sometimes they are so bad that we can’t even see our garden. I’ve developed an allergy to the dust, and this season is hard for me,’ says Asel Sheruyenova, 26, who moved to Jana Zhanbay after marrying, having previously lived in the region’s main city, Atyrau, located on the Ural River, near its mouth.

‘Every year we dig, and the sea keeps moving away. It feels like we’re chasing it,’ says a young employee of Atyrau’s municipality, who enjoys weekend barbecues by the Ural River. The local government in Atyrau has been continuously dredging the mouth of the river to allow boats to reach the open sea and to help fish migrate upstream.

From the end of the asphalt road, it’s another ten kilometres to the Ural’s mouth, where two large excavators are digging out the sea’s bed to form a 2.5-metre-deep, 40-metre-wide channel.

Yet, it’s a Sisyphean task, as the water is only 20–30 centimetres deep. Fishing boats often get stuck in the mud, forcing their crews to push them free.

‘It feels like the Caspian is heading for the same fate as the Aral Sea. The solution is political and beyond us,’ says the civil servant. Sitting around a low table with his friends, he shares grilled carp and duck skewers while dressed in a camouflage-style tracksuit.

The Aral Sea, once the world’s third-largest lake, is 1,200 kilometres from the Caspian Sea on the eastern border of Kazakhstan. It shrank by nearly 90 per cent at the turn of the century due to its waters being diverted to agricultural use. The then UN general secretary Ban Ki-moon described it as ‘one of the planet’s worst environmental disasters’.

The declining level of the Caspian Sea not only affects biodiversity and fishing, but also has an impact on river and maritime transport, tourism and even oil and gas production. Offshore platforms depend on boats to transport workers and equipment, and they need rapid response in case of accidents.

‘In the short term, it’s a major ecological crisis with no way out. The biggest catastrophe would be an accident on an oil platform. We have no assurance that a ship could intervene quickly because of the drop in sea level,’ warns Arman Khairullin, an environmental activist and independent deputy of Atyrau Regional Council.

He emphasises that the sea is managed by multinationals that prioritise immediate profit. The region is home to many of the industry’s biggest players, including Shell, BP, Total, Eni, ExxonMobil, Chevron, China’s national oil company and the Japanese giant Inpex.

In response to the decreasing sea level, oil companies have initiated their own dredging operations to maintain access to oil platforms. However, environmental activists have raised concerns that these activities could further degrade the already fragile maritime ecosystem.

Across the border, in Russia, where the shift in coastlines is less severe (five to seven kilometres on average), many fishers reach the sea thanks to dredging. But anticipating difficulties in reaching the ports of Olya and Astrakhan, Russian authorities have started building an additional port in Dagestan province that would be able to dock cargo ships.

Time is running out to make decisions that could reverse the decline of the Caspian Sea and the deterioration of coastal areas. Not only Kazakhstan, but also Azerbaijan and Iran are increasingly expressing concern. The key lies in better distribution of the waters of the Volga River.

Kazakhstan has attempted to address the mismanagement of transboundary water resources without success. ‘As far as the Ural and Volga are concerned, despite the Russian side’s willingness to discuss the problems, they are not taking any concrete action; they are just following their national interest without thinking about the other Caspian countries. They don’t want to suffer any economic loss by releasing more water to Kazakhstan,’ says Laura Malikova, chairperson at the Kazakh Association of Practising Ecologists.

Some experts in Kazakhstan are calling for the Caspian crisis to be included on the agenda of the COP 29 climate negotiations, which will be held in the Azerbaijani capital from 11 to 22 November.

It will more certainly be on the agenda in 2025 at the COP 7, the next Conference of the Parties to the Tehran Convention, the institutional mechanism for environmental protection in the Caspian region, which brings together Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Iran and Azerbaijan.

This article was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe. In Russia, Natalia Paramonova and Vladimir Sevrinovsky contributed to the reporting.