A campaigning group of mothers is calling for a ban on wood-burning stoves as evidence mounts on their threat to health

By Tom Howarth

It started as a group of mums shocked and concerned to discover they were living in the UK’s most polluted streets. Just five days into 2017, Brixton Road in Lambeth, London, had exceeded the legal limit for levels of toxic air pollutants for the entire year. This grim statistic came to signify just how out of hand the capital’s air-quality problem had become. Traffic pollution and the smog from wood-burning stoves were turning the streets of South London into a health hazard, along with vast swathes of the country and other cities and towns worldwide.

Jemima Hartshorn, a mother caring for her new baby, was living around the corner from Brixton Road

at the time. ‘I was on maternity leave after having my first child and living in Brixton, which at the time was the pollution hotspot in the UK,’ she says. ‘I, alongside other parents I knew, was becoming incredibly worried about the impact this was having on children in the capital, so we decided together that we wanted to do something about it.’

This quickly grew into Mums for Lungs, a grass-roots campaign group that has been lobbying for clean air in London and beyond ever since.

‘In the beginning, we were just a small group campaigning locally and having meetings in each other’s kitchens,’ Hartshorn explains. What began as a gathering of four concerned parents in Brixton has evolved into a community of hundreds of volunteers and supporters in all corners of the country.

Initially, their focus was mainly on the obvious pollution caused by cars and lorries. Their latest campaign, however, is taking on the growing menace of the tiny but lethal particles produced by wood-burning stoves. ‘We were shocked to realise what a huge proportion of harmful air pollution was coming from domestic wood burning,’ Hartshorn explains.

PARTICULATE MATTERS

Wood-burning stoves, or ‘log burners’ as they’re often called, have become increasingly popular in recent years. About 1.5 million UK households now have one, with an extra 200,000 added annually, according to the trade association the Stove Industry Alliance (SIA). But as more and more Britons turn to wood burning as an alternative heat source at home, concerns over its impact on the air we breathe have started to grow.

In much the same way that burning fuel in your car releases harmful pollutants, so too does burning wood. ‘The huge problem, though, is that [a log burner] emits huge, huge amounts of particulate matter – tiny bits of soot,’ says Hartshorn.

Of specific concern to campaigners and health care officials alike are small particles less than ten and 2.5 micrometres in diameter, known as PM10 and PM2.5 (the PM referring to particulate matter). Research commissioned by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) has shown that even the most ‘eco-friendly’ wood-burning stoves emit six times as much PM2.5 per hour as a modern heavy goods vehicle. In 2021, wood burning accounted for 27.3 per cent of particulate matter in the UK, industrial production 13.4 per cent and traffic 12.9 per cent.

All in all, PM2.5 emissions from domestic wood burning – which, to be fair to log burners, also includes bonfires and open fires – increased by 124 per cent between 2011 and 2021.

HEALTH IMPACTS

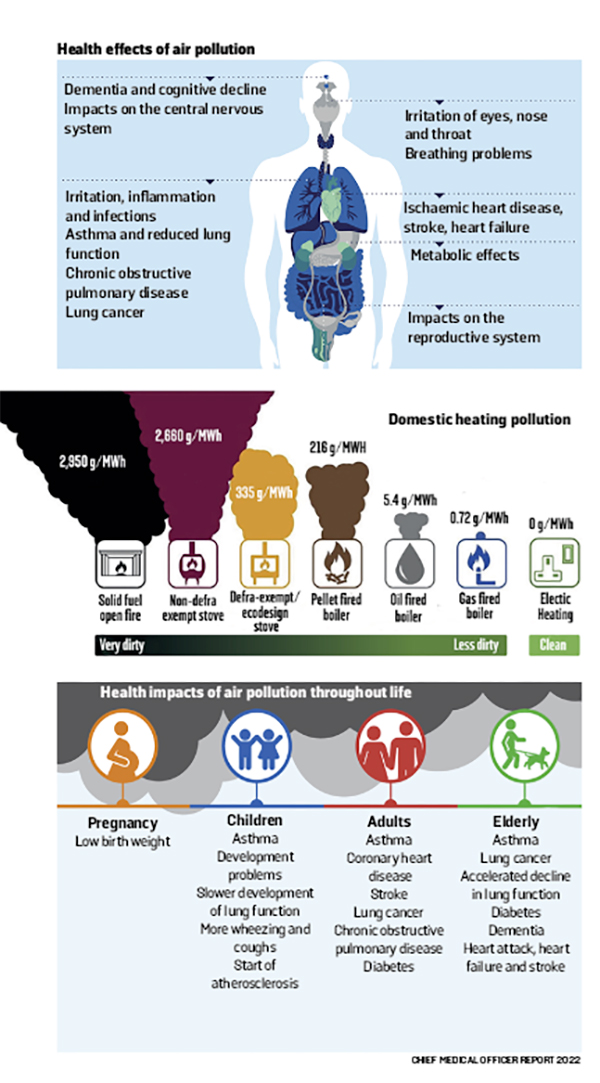

PM2.5 is an exceptionally troublesome type of pollutant by nature of its small size. Unlike larger particle types, it’s capable of penetrating deep into the respiratory system, wreaking havoc on the body from within.

Exposure to particulate matter is associated with a range of adverse health effects, including impaired lung development and function, worsening of conditions such as asthma, allergies, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pulmonary fibrosis, and an elevated risk of lung cancer.

Often, we associate such health risks with the air we breathe outside the home; however, there’s mounting evidence that not all of the pollution from your stove escapes through the chimney. ‘Understanding the impacts of the air pollution that we breathe indoors is in its infancy compared with the huge numbers of studies on outdoor air pollution,’ explains Gary Fuller, an air pollution scientist at Imperial College London, before pointing out that ‘indoor studies are producing new evidence on this all the time’.

He adds: ‘For example, last year, a study of 50,000 women in the US found a [43 per cent] increased risk of lung cancer in those that used wood heating at home compared to those that did not.’

The research Fuller is referring to is part of a study that tracks the health of women whose sisters have had breast cancer. It concluded that ‘even infrequent exposure to indoor wood smoke is associated with a higher incidence of lung cancer, including among [non] smokers’.

Beyond the self-evident human costs of PM-related illness, the government now estimates that the total cost due to PM2.5 to the NHS and social care in England alone will be £5.1 billion by 2035; a figure that climbs to £9.4 billion ‘when diseases with less robust evidence are included’.

‘We thought that the days of air pollution from home fires were left behind in memories of the 1950s and 1960s, but they’re back,’ said Fuller. ‘Home burning of solid fuel is one of the largest sources of primary particle pollution (PM2.5) in the UK, greater than the particles from the tailpipes of all of the vehicles on our roads.’

REGULATION ISSUES

While many people enjoying a cosy evening next to the fire this winter might be unaware of the potential health risks associated with domestic burning, campaigners, scientists and politicians are increasingly paying attention. ‘Where we are [on] wood burning now is where we were on cars seven years ago,’ Hartshorn says. ‘And [since] then, as with cars, the debate has moved really strongly forward.’

January 2022 saw the introduction of the Ecodesign Regulation in the UK, which stipulates minimum standards for efficiency and emissions of solid fuel heaters such as log burners manufactured or sold after this date. Wood burners installed before the regulations were introduced are exempt.

The new ecodesign regulations were well received at the time, with campaigners such as Simon Birkett, founder and director of Clean Air in London, calling them ‘an important step on the path to banning wood burning in urban areas’. But do ecodesign stoves solve the problem? Well, not exactly.

In his 2022 annual report, chief medical officer Professor Chris Whitty took a special look at air pollution, setting out where we can and should go further to reduce it. The report notes that ‘solid fuels are by far the most polluting method of domestic heating’, and that even the new ecodesign stoves emit 465 times more PM2.5 than a gas-fired boiler per unit of energy. Evidently, the new stoves are better than open fires or older models, but they are by no means a silver bullet.

Around the same time that ecodesign stoves went from exception to rule, the 2021 Environment Act entered into force. Under the new law, many parts of the UK were designated ‘smoke control areas’ (SCAs), where residents and businesses were now only permitted to burn unauthorised fuels such as wood if they’re using a DEFRA-approved ecodesign appliance. Those found flouting the rules can now be fined up to £300 and criminally prosecuted, which can result in fines of up to £5,000, in accordance with the new provisions.

However, freedom of information (FOI) data published by Mums for Lungs last year has found that local authorities are woefully ill-equipped to take action. Despite more than 10,600 complaints being received by local authorities since the implementation of the Environment Act, only one prosecution and three fines have been issued. Two-thirds of the complaints weren’t followed up at all, and 80 local authorities stated they weren’t using the new measures on wood burning. Mums for Lungs cites confusion over the new regulations as one possible reason for this lack of enforcement, as well as ‘cuts to local authorities’ environmental budgets’.

In 2021, wood burning accounted for 27.3 per cent of particulate matter in the UK, industrial production 13.4 per cent and traffic 12.9 per cent

Chief Medical Officer’s report on pollution 2022

‘Obviously, the compliance rates – who knows if they’re high or low or whatever – are impossible to enforce; councils don’t even try because it’s impossible,’ Hartshorn says. ‘They can’t get into anyone’s home. So, as we’ve seen from our FOI data, nothing has changed.’

In an attempt to strengthen the hand of local authorities, the government announced plans in January of last year to tighten the limits that new stoves in SCAs must meet, from five grams of smoke per hour to a maximum of three. The subsequent ‘air quality strategy: framework for local authority delivery’, published in April and updated in August, weakened this language somewhat, promising instead that the government would ‘consult on tougher stove standards for SCAs, potentially lowering the smoke limit for newly installed stoves from 5g smoke per hour’. As of December, DEFRA was still ‘developing’ its policy but wouldn’t offer a timeframe.

HEAT SOURCES

According to experts, campaigners and the government, the simplest way to reduce harmful emissions from burning wood is to avoid doing it where possible. In the UK, only four per cent of homes using solid fuel as a heat source rely on it solely. Where other options exist – namely, oil, gas and electric – using them will dramatically decrease the levels of harmful PM ejected into the air, both inside and outside the home.

For those still wishing to enjoy the comfort of a real fire, switching from an open fire or an older model of stove will serve as an improvement. ‘Several studies have been made of communities where [the effects of] wood and solid fuel burning has been drastically reduced by swapping old stoves for new models or by replacing them with electric heating,’ Fuller notes.

Erica Malkin, communications manager at the SIA, agrees. ‘Replacing an open fire with a modern stove can reduce PM2.5 emissions by up to 90 per cent and by up to 80 per cent when an older stove is being replaced,’ she says.

It’s also worth noting that while many homes don’t solely rely on wood burning for heat, the volatility of energy prices over the last two years may, at least in part, have served as a driver for its uptake. ‘Having a stove as a secondary heat source offers consumers a financial cushion against fluctuating energy prices,’ Malkin says.

Using properly dried wood is another important step. For example, burning dry wood with a moisture content of 20 per cent or less can reduce emissions by 50 per cent compared to a log that hasn’t been dried, according to the government’s environmental action plan. Properly drying firewood requires storing it for anywhere between six months and three years, depending on the conditions, if you don’t have a drying kiln to hand, that is.

Christmas trees pose a particular problem – many are chopped up and burnt at home rather than recycled. ‘I will presume that most people who have a woodburner and have decided to burn their Christmas tree are going to be burning 2023’s Christmas tree quite soon,’ Hartshorn points out.

She’s probably right to assume this. Even ex-prime minister turned Daily Mail columnist Boris Johnson concluded a recent piece by affirming his right to burn his own Christmas tree if he so wishes: ‘It is not yet illegal to burn your own Christmas tree – or any other logs you choose – in your own home. So quick, before they ban it, that is what I am going to do.’

Indeed, it’s not illegal to burn wet wood just yet, although it is now illegal to sell it in small quantities. In terms of Christmas trees, most experts, the London Fire Brigade included, recommend recycling them instead.

A SOLID BAN

Looking ahead, campaign groups such as Mums for Lungs are calling for government action. In the short term, they’re asking for proper health warnings on stoves. ‘You don’t buy cigarettes without a warning these days; you shouldn’t buy stoves without a warning,’ Hartshorn says.

‘Given the confusion and lack of enforcement of new rules, Mums for Lungs are calling on the government to simplify the situation by phasing out domestic wood burning where alternative heating exists,’ she adds. The group is calling for a halting of sales of new wood stoves by 2027 and a ban on the use of wood burners unless they’re the only source of heat by 2032.

‘Because pollution has a much bigger impact at much lower levels than we previously expected, wood burning has no place,’ Hartshorn concludes.

Fuller agrees. ‘We need to move away from a message that solid fuel heating is a normal way to heat a home,’ he says, ‘and instead leave it as a polluting relic from the last century’. l