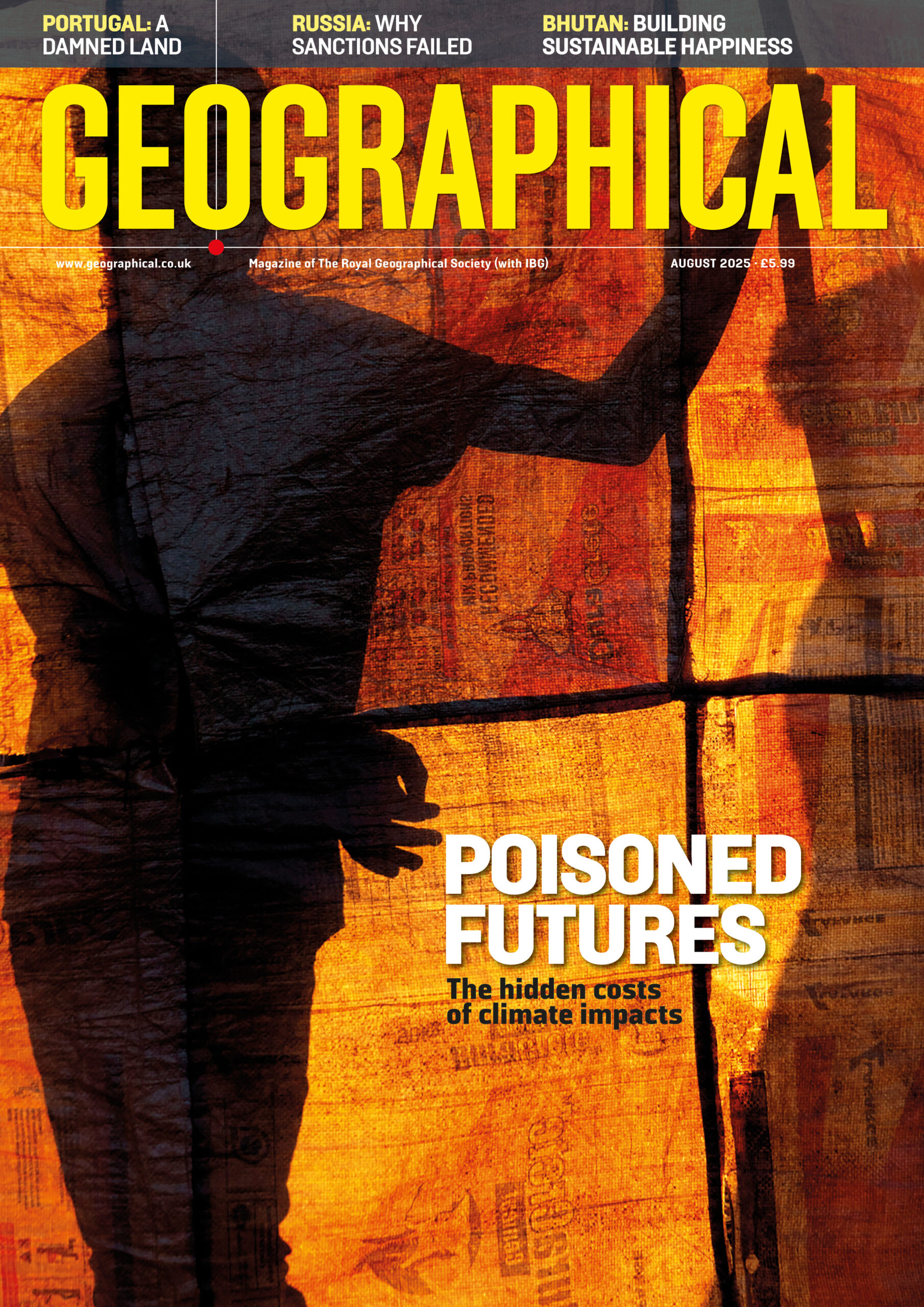

Novelist, poet and storyteller Nii Ayikwei Parkes travels to the Caribbean to research his past – a complex heritage that has been fractured and scattered by the impact of the slave trade

One of the more fascinating remnants of the brutal chattel slavery era in the USA is the catalogue of advertisements in newspapers about enslaved Africans. One, from 1760, proclaims that ‘Negroes, just arrived from the Windward & Rice Coast’ are for sale; another, from the 27 August 1761 Maryland Gazette reveals that an escaped slave ‘who was imported in 1760’ and barely speaks English ‘can work at the Smith’s Trade, having been employed in his own country in that way’. The use of Rice Coast here – to describe the region of West Africa from which I hail – isn’t accidental; it was to signal to prospective buyers that the captured people for sale were skilled in the planting and harvesting of rice. The adverts demonstrate that colonialism and its associated trade in Black bodies involved the removal of skilled people from their native lands to be exploited in other colonised lands.

One of the effects of that removal is that every person removed lost the opportunity to pass their skills down to a younger generation of Africans, leading to losses of both skills and learning. When you consider that by 1760, the slave trade had been going on for more than 200 years, you begin to get a sense of the tangible scale of the economic and socio-cultural impact of colonialism. However, even greater, perhaps, are the intangible impacts, related to the destruction of cultural systems, that have led, in my own case, to a hesitancy, timidity and malaise, and the kind of rootlessness I sometimes feel, even towards my own name – Parkes – which was imprinted on my family via its encounter with colonialism and slavery.

Of course, because the people who were removed and taken to all corners of the globe carried with them the cultures with which they had grown up, they’ve been key drivers of what we now describe as Caribbean culture. The rice I’ve already mentioned lives on in dishes right across the Caribbean, especially in the near-ubiquitous rice and peas.

In his journals of his travels to West Africa in the 15th century, Venetian slave trader Alvise Cadamosto describes the people he encounters as ‘talkative, and never at a loss for something to say’ and ‘charitable, receiving strangers willingly’. Contemporary travel adverts for Jamaica and Trinidad reflect these traits: Trinidad, known for liming – the act of just hanging out and chatting – and Smile Jamaica having been the slogan Bob Marley helped make famous for Jamaica.

It’s into such warmth that I arrived in Guadeloupe for the first time in search of traces of the lost family that Thomas Parkes, whom we believe to be the first Parkes to have started a family back on the continent of Africa after returning from the Caribbean as a boy. Tante Armelle, the woman who meets me, is the mother of a friend from my semester abroad in France, while I was studying in Manchester in the mid-1990s. My mission is simple: to get to Guadeloupe’s archives at Gourbeyre, Basse Terre, to begin the search for whatever threads might lead me to ascertain if Thomas’s mother had other children who remained in Guadeloupe – lost family.

Lost family is the very question that fuels my as-yet-unfulfilled desire to visit Jamaica. Indeed, if we think of the Caribbean as a place where stolen things were taken, it’s easier to understand many different motives that drive people to visit; the thieves visit to check that their booty still has value, the victims go to sift through the lost and found cupboard.

In my case, Guadeloupe isn’t the only island I’m visiting because, as part of research I’m doing as part of a fellowship at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center, I’m also looking for cultural markers that derive from African cultural systems. So, before Guadeloupe, I’ve already been to St Lucia and Trinidad, and will visit Grenada before I return to Boston.

The markers I seek are things such as the new language forms that African people evolved from the colonial languages, with both Kreyol (French) and Patois (English), for example, dropping gender markers such as she/her and he/him in favour of I and im respectively, mirroring West African languages, which don’t have them; things such as a reverence for the dead and unseen; things such as the food that’s spread before me at the family gathering summoned by Tante Armelle on my return from the archives at Gourbeyre, preceded by the local cocktail P’tit Punch.

Directly in front of me, across a long table that seats 14 members of Tante Armelle’s family, is her mother, 100 years old, talkative and elegant in a white linen dress. Between us are two dishes that tell a little bit about how colonialism has shaped the Caribbean: to my left, ragoût de porc, spiced with onions, thyme, bois d’Inde, girofle and garlic; to my right, colombo de poulet, with the key ingredient of colombo powder. When I taste the dishes, I know the flavours intimately but, my French being rusty, my hosts are unable to explain bois d’Inde and girofle to me. The colombo de poulet, however, is what we would call chicken curry in England, reflecting the influence of indentured Indian and Chinese workers shipped to the Caribbean during the colonial era, but with an odd ingredient that reeks of the French – mustard.

Colonisation, because of its focus on profit over people, is always piecemeal, and that haphazard manoeuvring leaves its marks on both coloniser and the colonised. As we eat, we discuss my travels in the African diaspora and we soon discover that one particular dish, a street food, appears to have travelled from West Africa to every colony to which Africans were shipped – they call it acra, which sounds like the capital of the country in which I grew up; I call it akara or koose; in Brazil it’s called acarajé; in Trinidad and St Lucia, it’s accra. Fritters, usually made from bean flour, either plain, or with a range of fillings including saltfish, they’re also sometimes made with root vegetables such as cassava.

Later that evening, I look up bois d’Inde and girofle to find that they are pimento and cloves, bark and seeds that form key elements of what we know as jerk seasoning, but that also reflect the cooking methods of forest hunters in West Africa, especially the Asante – referred to in some literature as Coromantee or Kromanti – who seasoned and cooked their kills either to preserve the meat, or to assuage their hunger.

Because of colonisation and its attendant forced migrations, many African and Indian families are scattered, not knowing where in the world they might have lost unknown relatives. In the Caribbean, forced breeding weakened the foundations of family systems known in Africa. Family folklore held that my paternal grandfather migrated from Sierra Leone to Ghana because his family were Asante, which makes sense historically because we’re descended from Jamaican Maroons, who are predominantly of Asante heritage.

However, with each migration, someone is left behind, whether in Jamaica or Guadeloupe or Sierra Leone, and the next generation is left with more threads to follow. Along these threads is a commerce of influences that creates a constantly shifting culture and new social structures to embrace prevailing realities. Where we can’t fill the gaps, we imagine.

This is perhaps why I am a storyteller – because of colonialism, because to stay sane in a world where loss is your heritage you need an abundance of myth.

I think I’m also a storyteller because I know my story isn’t unique; there are many families with an ancestor resettled in Africa after being trafficked to the New World, but their stories are buried in the silence trauma brings.

But there’s a silence that speaks.One of the best elements of speech my Ghanaian upbringing has gifted me is the non-word ‘Hmmm’. I have found it on occasion in the Caribbean; one night in St Lucia, drinking rum with my landlady, Auntie Mary, when she told me about her Akan grandmother, for instance.

Hmmm has a weight that no quantity of words can match. It’s the perfect lexicon for histories where we know so much, but none of it’s written – for what the American poet academic Nathaniel Mackey calls ‘wounded kinship’. It’s the sound I make when I taste ragoût de porc with a family I didn’t come looking for in Guadeloupe – to say that I know you, but I don’t know exactly how.