After teetering on the brink of extinction, northern Spain’s brown bear population is growing. Chris Fitch explores how local communities are responding to their new neighbours

You would think that a bear the size of a small car would be fairly straightforward to spot. Doing so equipped with powerful binoculars, accompanied by a guide patiently explaining exactly where to look, should make it even easier. But as I scanned the mountainous landscape before me, pausing briefly to check whether various bear-shaped objects were, inevitably, just another rock, it became clear that this was going to be considerably more challenging than first anticipated.

There had been no guarantees. ‘We will try to see the bear,’ were the cautious words from Victor García, a guide from tour company Wild Spain Travel. So much weight hung on that word ‘try’ that it was starting to buckle under the pressure.

Bear watching is very different from, say, a safari, where a vehicle can park right next to an animal and provide a front row seat. With bears, distance is mandatory and patience critical. These crepuscular animals (active at dawn and dusk) emerge only when the temperature is optimal. Even when waiting in the perfect spot at the perfect time there are no assurances. Therein lies the thrill when one does make an appearance.

The surrounding mountains were bathed in the scarlet light of an impending sunset. Despite the warmth of the day, fragments of crisp winter snow clung to the peaks. Huge rock strata rose dramatically from the valley, lying across the landscape like creased laundry. Silence, broken only by the crunching of gravel as a handful of fellow aspiring bear-spotters shifted their weight from one foot to the other.

Suddenly, a flurry of activity. Faces disappeared behind metre-long camera lenses, amid whispers that not just one, but two bears had emerged, far off on the opposite side of the valley.

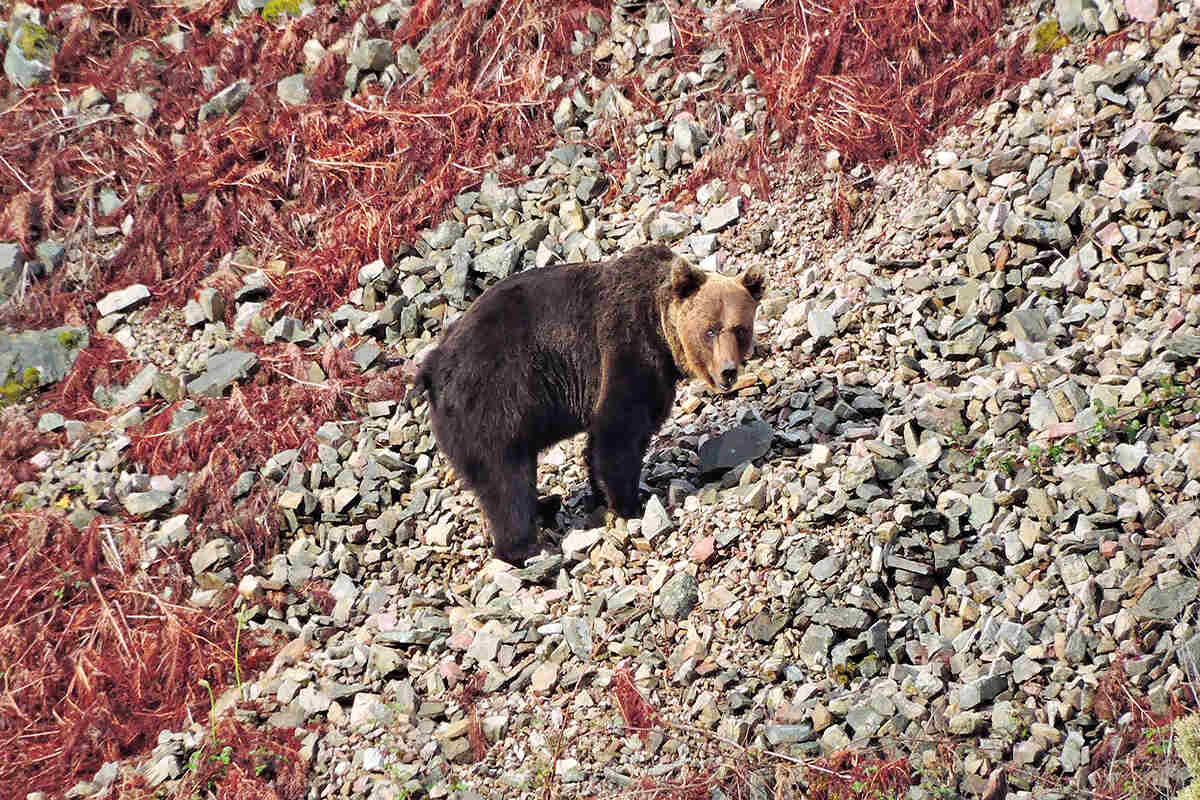

‘You can see that the male is smelling and going the same way as the female,’ said Victor, his normally booming voice reduced by several decibels to something more wildlife-appropriate. Once I’d located the animals, I saw what he meant: a smaller bear running – if you can call her quick-footed shuffle over the rocks a run – with a larger bear sniffing in pursuit. The male paused for a moment, grabbed a young tree and gave it an almighty shake, as though letting out some pent-up frustration. Dropping back onto all fours, nose to the ground, he was quickly on his way again, scurrying after her into the descending twilight.

Back in the day

Spain was once full of bears. During the 14th century, they were documented living as far south as Andalucía, on the Mediterranean coast. Initially, these animals were somewhat protected, with only high-society elites allowed to hunt them. Over time, their prestigious status waned and non-aristocrats were permitted to organise bear hunts.

It became a free-for-all. Written records from the 16th and 17th centuries detail payments made to hunters who undertook the dangerous job of killing bears (and wolves), which were considered alimañas, vermin. Combined with the high value of bear skins and fat, they provided a handsome income. Renowned hunters – such as 18th- and 19th-century icons Manuel Álvarez and Francisco Garrido Flórez, who racked up confirmed kills of 48 and 66 adult bears respectively – were heralded as heroes. They were so successful that by the start of the 19th century, the brown bear had been almost wiped off from the Iberian Peninsula.

On Spain’s northern coast, adjacent to the Cantabrian Sea, lies Asturias. Around the size of Devon and Cornwall combined, and home to roughly a million Spaniards, it’s a region with an illustrious history. Victory for Christian Visigoth forces over Islamic Moors at the Battle of Covadonga in 722 CE led to the founding of the Kingdom of Asturias, and was widely seen as the starting point for the seven-century Reconquista. Consequently, this small corner of territory is often referred to as the birthplace of the Spanish nation. The region’s importance lives on in that fact that the title of Prince or Princess of Asturias is anointed upon the heir-apparent to the Spanish throne, the equivalent of the Prince(ss) of Wales.

Around 80 per cent of Asturias is covered by the Cantabrian Mountains. A striking landscape that wouldn’t look out of place in the wilds of Patagonia, it contains several peaks that surpass 2,500 metres in elevation. These mountains are a rare spot in which Spain’s bears clung on to survival, evading hunters by disappearing into the rugged terrain. Hence the name – the Cantabrian brown bear – for the specific subspecies of Ursus arctos that lives here, U. a. pyrenaicus.

But even Asturias witnessed a severe decline. As recently as the mid-1990s, there were as few as 50 bears living across the region, with only a handful of breeding females. Worse still, having been split into two subpopulations (one in the west, a smaller one in the east), the prospect of stabilisation, let alone a healthy recovery, was further weakened. Extinction beckoned.

Don’t call it a comeback

The morning air was freezer-cold, a faint haze lingering. By the side of a winding mountain road, I once again stared out at a broad panorama – a deep valley rising to multiple treeless summits. Even with years of practice, I wondered how anyone could locate a wild animal within such a scene. Only thanks to the experienced eyes of rangers and their high-powered telescopes was I soon watching a family of bears – a mother and two cubs – slowly walking on the opposite side of the valley.

It’s extremely difficult to get a sense of scale at such a far remove. The mountains warp any innate understanding of height or distance, flattening space, playing hypnotic tricks on the eye. From afar, these bears could easily have been the size of their North American cousins, the grizzlies. Although the Cantabrian bears are smaller, they’re certainly not small, with males weighing up to 200 kilograms. It’s difficult to see detailed tones from such a distance, but there was a creamy caramel colour to their fur, perhaps lightened by the golden morning light.

Fernando Ballesteros, a bespectacled local biologist, watched with me. The bears lumbered along a tree line around the edge of a distant grassy clearing, the youngsters wandering around, occasionally doubling back, getting to know the environment. As Fernando explained, this is no longer such a rare sight. ‘If you see a graph of females with cubs, the graph is sharply declining, then suddenly starts to grow…’ he said, drawing a giant V in the air with his finger to illustrate.

The turn in the Cantabrian bears’ fortunes coincided with the 1992 founding of Fundación Oso Pardo (FOP), the Brown Bear Foundation, of which Fernando is a 20-year veteran. Much of the organisation’s energy was derived from founder and president Guillermo Palomero García, a carnivore enthusiast. From the beginning, his focus was on achieving social acceptance of the bear in rural areas.

To make this happen, FOP’s opening move was to target illegal hunting, bringing an end to shooting and the setting of traps. Even though bear hunting had been banned nationally since 1973 (and restricted, with minimal enforcement, over preceding decades) illicit poaching remained widespread. FOP focused on finding and disabling the rudimentary traps and snares used by poachers – removing thousands – and making it socially unacceptable to install new ones. Thirty years ago, to find a bear missing one or more limbs, the consequence of an encounter with a snare, wasn’t unusual, but such sightings today are extremely rare.

The end of poaching-related mortalities has turned the bears’ fortunes around. The Cantabrian brown bear population, once facing elimination from this landscape, now stands at at more than 400, and continues to increase by an additional 30–40 individuals annually. Still endangered, yes, but on a steady path to recovery.

For the first time in generations, local communities are discovering how to live in an environment with more bears, not fewer. Unsurprisingly, not everyone is enthusiastic about this development. Human–bear conflict remains a significant issue, so FOP, their illegal-poaching mission largely complete, now promotes a culture of cohabitation with the bear population. Funded by organisations such as the European Nature Trust, it’s re-educating communities about traditions lost after a century or more of minimal (if not zero) bear presence in the environment.

For example, beekeeping is a popular pastime and economic activity in Asturias. Unfortunately, as anyone who has read Winne the Pooh knows, bears are also fans of honey, and younger animals display no fear of human settlements, associating them with food and safety, not danger. While the regional government runs a compensation scheme that pays nominal fees to people whose livestock, crops and/or property are damaged, keeping wild bears from destroying hives is important for maintaining the peace.

Traditional methods for keeping them away included building structures called cortines (alvares elsewhere in Spain) – stone structures with high walls that make it difficult for ursine opportunists to reach the golden treasure within. While a handful are still in use, the modern version involves electric fencing. FOP has donated fencing to more than 2,000 beekeepers and visits properties to ensure that they’ve been installed correctly. With in-person demonstrations, brochures, tutorials, masterclasses and other educational means, FOP is restoring critical cultural knowledge about cohabitation.

Follow the trail

One enduring problem is the reluctance of female bears to migrate. Males will happily wander Iberia, into neighbouring regions such as Cantabria and Castilla y León, and even northern Portugal. But without females to breed with, they inevitably return home. With subsequent mothers and cubs also sticking to familiar landscapes, the cycle repeats. Such a pattern threatens to overload the contemporary habitat with bears while surrounding territories remain bearless.

One aspiration is to combine the east and west subpopulations within the Cantabrian Mountains. Encouraging these two groups to mix would expand the animals’ range beyond their comfort zones, reducing pressure on existing habitats, as well as improving the genetic health of the subspecies.

‘The philosophy here is to colonise new lands,’ said Victor. He led me to a remote location to demonstrate one way this is being achieved. The scene around us appeared to be an ordinary tree planting operation. Surrounding fields were feral, with tall grasses, daisies and buttercups, large prehistoric-seeming unfurling ferns, and stinging nettles scratching my legs. The air was full of floating dandelion seeds, and a fragrant bouquet of cow dung. Crag martins overhead glided through the valley.

Around us were native cherry trees, explained Victor, planted by volunteers eight years previously. Wild bears have a varied diet, feasting upon everything from ants and bees, to young grass shoots and flowers, to acorns and beechnuts. But when summer rolls round, these fast-growing fleshy fruits are an irresistible favourite. By planting these skinny trees on farmland between the two subpopulations, FOP are luring the bears from one territory to the other, like cartoon characters following a trail of sweets. Another field populated by young trees was visible 500 metres away – the next stepping stone along this route.

Beyond bears

With bears now increasingly common in Asturias, bear watching has, almost by accident, become a viable tourist activity. When Spanish photographers and nature lovers began promoting the region during the 1990s, it helped to trigger a change in attitude among local communities, with bears seen less as pests and more as economic assets. As in many parts of the world, giving local wildlife a value, a reason for tourists to fill guesthouses and purchase local products such as handicrafts and honey, has helped to persuade people to accept the presence (and sometimes the inconvenience) of brown bears.

‘The people that were there when we were seeing the bears were local people,’ said Victor, referring to our first bear-watching experience. ‘People who, if they saw a bear, once preferred to shoot them with a gun. Now they are there with binoculars, or a telescope, or a camera to take pictures. That’s a big change.’

Authorities in Asturias are reluctant to over-promote bear watching – to make their tourism strategy all about trying to spot bears. ‘We want you to see the bears, but we really want you to enjoy the nature in which the bears lives, to get in touch with the people who are close to the bear, and get to know the local culture,’ explained Tatiana González, who is in charge of marketing tourism in Asturias. She had joined me for a final bear-spotting experience in the quiet settlement of La Peral, near the southern end of Somiedo National Park, and her words were accompanied by a soundtrack of cow bells and bovine bellows.

As the setting sun lit up a blanket of mist, the shadow of the western mountains cast an ever-lengthening darkness behind us, until only the highest peaks continued to glow. Scanning my camera across the terrain at full zoom, a dark, moving shape caught my attention. A bear ambled out of the forest before quickly disappearing – a young one, energetic. He tumbled down a small slope as though desperately trying to reach the bottom of the valley. A moment later, he composed himself and began a gentle stroll, slowly moving away from me. Pausing for a moment, he turned and galloped from sight. Moments such this can be fleeting, over in a matter of seconds, but the impact on the region, and the people who live here, will hopefully endure for considerably longer.