Wildlife photographer Ursula Franklin captures the fascinating lives of penguins in the Southern Hemisphere

A pink tideline stretches along the beach on Deception Island – the caldera of a 30-kilometre-wide active volcano, most of which lies beneath the surface of the Southern Ocean. It’s formed by the bodies of thousands of pink krill that have been cooked alive by the hot, volcanic waters and washed ashore. These krill also form the main diet of the island’s best known inhabitants: the penguins.

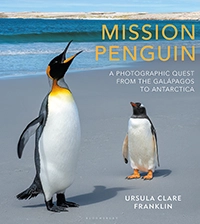

Despite being synonymous with Antarctica, only two of the 18 species of penguin can truly call the Antarctic continent their home: the Adélie and the emperor. The other 16 species of penguin have ranges as wide as the Macaroni (which can be found in both the South Atlantic and Indian oceans), as narrow as the Snares (which only breeds on the Snares Islands, New Zealand) and as far north as the Galápagos penguin (which has been known to cross the equator to feed). Ursula Franklin has made it her mission to photograph them all.

Want to learn more about penguins?

‘People often laugh and say that if I went on Mastermind, penguins would definitely be my special subject,’ says the wildlife photographer with a smile. Franklin has always had a fondness for penguins. But when she first set off on her self-appointed mission in 2012 – a project intended to lift her spirits after the loss of a loved one – she was by no means an expert. Today, she can recognise the tracks of a gentoo penguin (part of the brush-tailed family) from the distinctive marks its tail feathers leave in the sand. She knows their different behaviours from hours spent photographing them, occasionally up close. ‘When you go on expeditions, there’s always a five metre rule around the wildlife,’ says Franklin. ‘But nobody ever tells the penguins.’

Mission Penguin captures the joy that Franklin experiences as a wildlife photographer, while highlighting the ongoing challenges – and successes – facing different penguin colonies across the Southern Hemisphere.

Southern rockhopper penguins

Two southern rockhopper penguins leap onto the rocks of the near-vertical cliffs of Sea Lion Island, the Falklands, where they hop from rock to rock, attempting to reach the colony at the top before the next wave comes.

These colonies can be up to 60 metres above sea level, where the birds find space between the nests of black-browed albatrosses and imperial cormorants.

Chinstrap penguins

The unmistakable face of a chinstrap penguin. Chinstraps are extremely social and live in some of the largest, and noisiest, penguin colonies, sometimes exceeding 100,000 pairs on a single island.

Moseley’s rockhopper penguins

Moseley’s rockhopper penguins are monogamous and form lifelong partnerships. Ninety per cent of the species is found in Tristan da Cunha, the most remote human-inhabited archipelago in the world.

They breed in dense, noisy colonies on boulder-strewn beaches or in the dense tussock grass.

Gentoo penguins

After repeatedly dive-bombing this nest on Saunders Island in the Falkland Islands, a skua successfully dislodges the adult gentoo penguin, leaving its chick and hatching egg in a very vulnerable position.

As adults, gentoo penguins are the third largest of the penguin species and are thought to be the fastest swimmers, reaching speeds of 36 kilometres per hour. As young birds, however, they are prey for skuas, southern giant petrels, snowy sheathbills and – on the Falkland Islands – feral cats.

Adélie penguins

An Adélie penguin shakes to loosen its feathers. All birds moult, but unlike other birds, penguins shed all of their feathers at once – a process known as a ‘catastrophic moult’.

During this period, which lasts between two and four weeks, the penguin is forced to stay on land. Only once its new, waterproof coat has fully replaced the old will it return to the ocean to feed, by which time an adult Adélie penguin may have lost as much as 45 per cent of its body weight.

Emperor penguins

Emperor penguins, such as these in Snow Hill Island, Antarctica, can travel as far as 120 kilometres inland from the coast to reach their breeding colonies.

Chicks are often left in crèches with other young penguins as their parents cross back over the ice to feed.

King penguins

A colony of some 100,000 king penguins in South Georgia.

Despite near decimation from commercial exploitation during the 19th and early 20th centuries, when seal hunters turned to king penguins as a source for oil, there are now an estimated 2.2 million adults and population numbers are increasing.

Yellow-eyed penguins

Yellow-eyed penguins, which aren’t as social as other penguins, are commonly seen alone. Like the little penguin – the smallest penguin of all – the yellow-eyed penguin is the only species in its genus.

They are one of the rarest penguins, numbering between 2,600 and 3,000 individuals, and the population on New Zealand’s South Island faces increasing pressure from development and agriculture. Like Humboldt and Magellanic penguins, they are often recorded as fishing bycatch.

Mission Penguin: A photographic quest from Galápagos to Antarctica is published by Bloomsbury Wildlife and is available to purchase

Mission Penguin: A photographic quest from Galápagos to Antarctica is published by Bloomsbury Wildlife and is available to purchase