In this edited extract from The Future is Fungi: How Fungi Can Feed Us, Heal Us, and Save Our World, we highlight mushrooms and other fungi that are used for food, medicine and their psychotropic effects

By Michael Lim and Yun Shu

To best appreciate the importance of fungi, let’s start at the intersection of science and history. Fungi diverged from animals one billion years ago. So close are the fungal and animal kingdoms that taxonomists speak of a superkingdom that combines the two: the Opisthokonta. This billion-year-old divergence was only recognised in 1969 when ecologist Robert Harding Whittaker formalised the importance, scale and diversity of fungi with the new classification. Previously, fungi had been classified as plants and dismissed as lower-class organisms, tucked away in an obscure corner of the botany department.

The basic building blocks of fungal cell walls consist of chitin, the same material as the hard shells of crustaceans and insects. The cell walls of plants, in contrast, are built from cellulose. Like animals, and unlike plants, fungi are heterotrophs – they are unable to produce their own food and must instead obtain it from their environment. Animals opted to internalise their stomachs, while fungi pursued an external version. They secrete enzymes into the environment to digest food externally before absorbing it into their cells.

Fungi are inherently difficult to study in nature as the majority of species are microscopic or live underground; however, mycologists have made great strides in recent decades. Technological advances make it possible to identify fungal DNA in the environment. Unfortunately, the DNA is difficult to match up with known species because a comprehensive catalogue of fungal DNA doesn’t yet exist. To date, only 120,000 species of fungi have been identified. Using a complex process called DNA barcoding, scientists estimate that more than six million fungal species exist in nature, which means that 98 per cent are still to be discovered, highlighting the untapped potential of mycology.

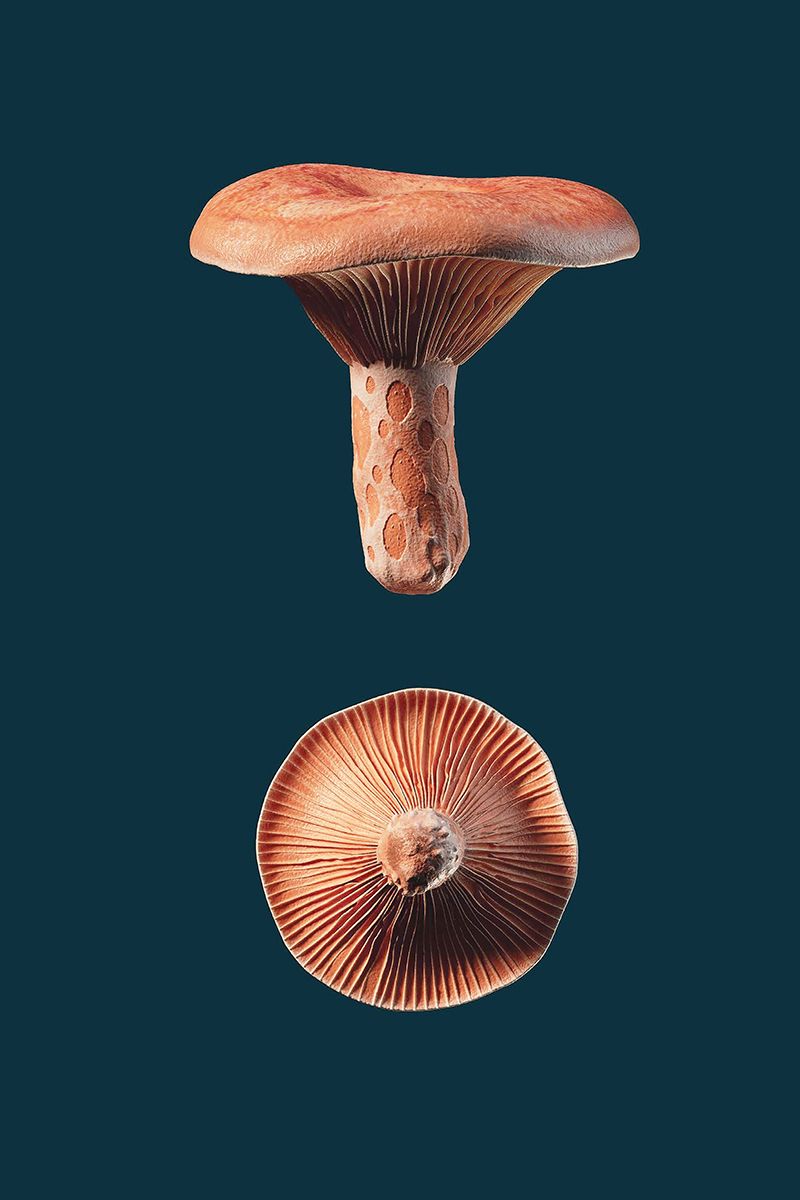

The fungal kingdom is incredibly diverse. Beyond the popular images of cap and stem mushrooms, there are clubs, corals, shells and balls, to name just a few. And mushrooms are just the tip of the metaphorical iceberg. In fact, only ten per cent of (known) fungi produce mushrooms. Yeasts, moulds and mildews are all fungi, yet most of these are invisible to the naked eye and don’t produce mushrooms at all. Turn over a pile of dead leaves in a forest and you’ll almost certainly see white, furry patches hitched to their underside. These white, cottony masses are mycelia, which are made up of individual strands of thread-like hyphae. Mycelia and hyphae compose the growing and feeding part of the fungus – also known as the vegetative stage. This structure typically exists within soil, where it allows the fungus to search for food while also creating and aerating soils in a way that benefits the rest of the ecosystem.

Underground mycelia also weave the forest into a dynamic network of incredible scale. Mycorrhizal relationships – in which fungi are associated with plant roots – are far more complex than a single partnership between a fungus and a plant. Hundreds of mycelia can be attached to one plant and, conversely, a mycelium can be attached to hundreds of plants. Mycelium is so fine that a teaspoon of soil can hold hundreds of kilometres of it. Over an area as large as a forest, that’s a long information highway for fungi and plants to relay resources and chemical signals across. And they do, constantly. It’s widely accepted that the carbon produced by one tree can be shared with its mycorrhizal partners and other trees. This was discovered by Suzanne Simard, an ecologist and professor at the University of British Columbia, and published in a 1997 paper in Nature. She called it the ‘wood wide web’.

Mushrooms, on the other hand, serve only one biological purpose: reproduction. They contain spores, the reproductive units of fungi, which function like the seeds of plants. Humans have made use of them for centuries. There’s a long history of using fungi for their medicinal qualities. Mushrooms have a starring role in traditional cultures due to their dual role as food and medicine. The wisdom of this duality is highlighted in an ancient Chinese proverb – yao shi tong yuan – which translates to ‘medicine and food share a common origin’. After all, what we consume every day provides the building blocks for our bodies to make and replace cells, and supports a healthy metabolism and strong immune system.

Over and above the nutritional value of mushrooms, the medicinal values long ascribed to them are now being validated using modern scientific methods. Microscopic fungi such as yeasts and moulds play a big part, too. But we’ve only just started to peer into the fungal medicine cabinet and harness their properties to treat human ailments. In the rush to create new medicines, it’s worth understanding what ancient cultures have used to great effect for thousands of years.

Fleming discovered penicillin by chance in 1928 when spores of the mould Penicillium notatum drifted into his lab and landed in a petri dish. He soon noticed a bacteria-free zone around the mould, suggesting that it produced chemicals that killed the bacteria completely. A decade later, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain from the University of Oxford began to search for high-yielding strains of Penicillium. Fruit and soil samples were submitted from all over the world and in 1943, a laboratory assistant named Mary Hunt sent in a cantaloupe covered in a ‘pretty, golden mould’. That mould was Penicillium chrysogenum and it yielded a tremendous amount of penicillin. The team developed the production process and companies in the USA and UK quickly mass-produced penicillin, the first antibiotics to be sold.

The main active compounds in psychoactive fungi are psilocybin and psilocin. So far, more than 200 species of fungi are known to contain psilocybin and they’re found across all continents except Antarctica.

Most famously used recreationally, psilocybin and psilocin are currently in phase II clinical trials to treat depression and many more clinical trials using psilocybin and psilocin are underway to help treat end-of-life anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, anorexia, alcoholism, smoking addiction and a whole host of other mental health issues.