This tiny marsupial was declared extinct but is now being returned to the wilds of the outback where the region’s First Nations people believe it first appeared on Earth

Words and photographs by Anthony Ham

From where I’m standing in Australia’s Great Sandy Desert, atop a sand dune overlooking Yunkanjini (Lake Bennett), I could travel north, south, east or west for more than 1,600 kilometres without seeing another person.

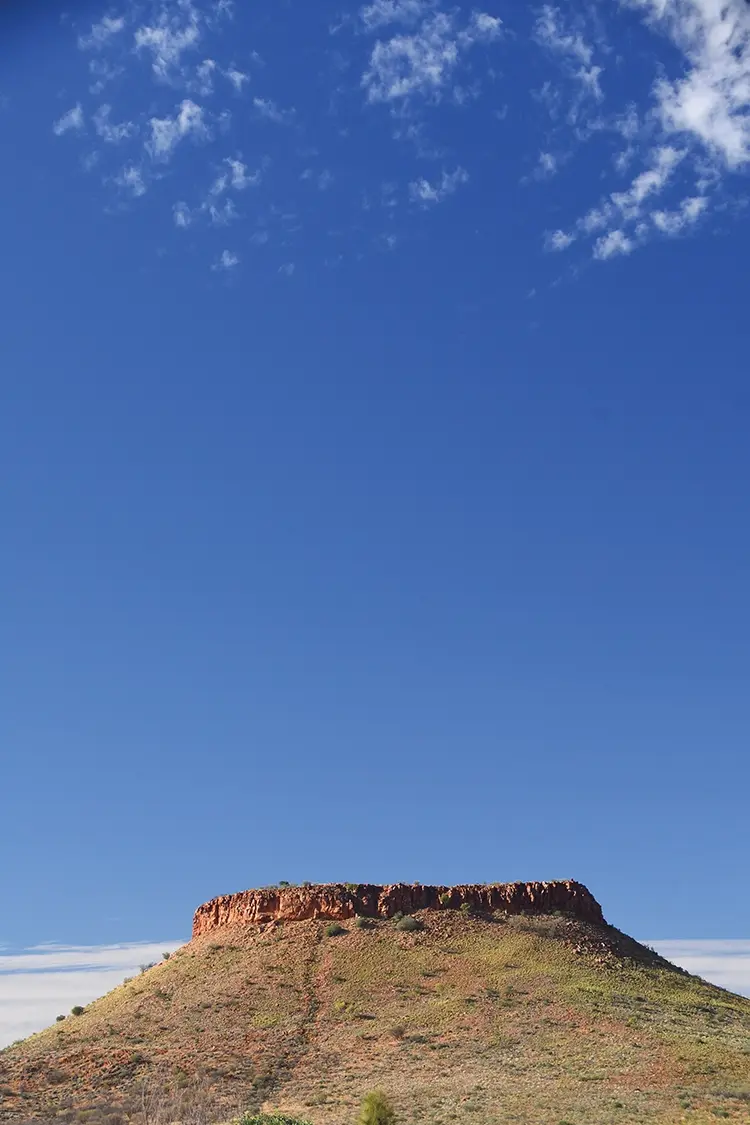

Mount Liebig, purple and sacred, rises away to the south, out beyond the salt-white lakebed. Red sands, ghost gums and distant desert massifs encircle to the east and north. Nothing interrupts the horizon away to the west. It’s like staring into an abyss.

Out here in Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary, in the very heart of Australia, it can feel as if the desert is beautiful, achingly so, but empty. To get here, to reach such a point of exquisite remoteness, I flew into the desert city of Alice Springs, in Australia’s Northern Territory, then drove north and then west out into the desert in a 4×4. Along the way, the roads narrowed and became tracks. Each kilometre that passed was like shedding a layer of city skin, leaving behind the noise and the clamour and all concerns about time.

A remarkable 18 per cent of mainland Australia is enveloped by deserts, and without knowing when the precise moment happened, I entered the Great Sandy Desert, Australia’s second-largest. It’s a world of big skies and big horizons, of winds gusting this way and that. And then, stillness and silence. But this desert isn’t empty, marked as it is by so many worlds unseen.

Like all Australian deserts, the Great Sandy is cross-hatched by songlines, by the songs and stories that brought the Earth into existence. For the region’s First Nations people, songlines are both a road map and an encyclopaedia. Newhaven lies close to the southern boundary of Warlpiri Country, which covers an estimated 140,000 square kilometres. Warlpiri Country is more than half the size of the UK, larger than the Netherlands, Belgium and Switzerland combined. It’s home to, at most, 5,000 people.

Nothing marks the boundary between Warlpiri Country and that of its neighbours, at least not to the untrained eye. Even so, many Warlpiri people know the tree or the rock or even the songline where their country ends and another begins.

Entwined in these stories of creation, people and landscapes are the animals that live in the desert. Newhaven is home to a myriad of ecosystems – red-rock desert outcrops, salt lakes, grasslands, sand-dune country, stands of desert oak and many more. When you drive its rusty-red laterite roads in the early morning desert chill, you must do so slowly, watching for blue-tongued lizards, great desert skinks and thorny devils.

What you don’t see much is large numbers of native mammals. And in this sense, the desert is empty, worryingly so. Australia has the worst record of mammal extinctions of any continent on Earth, and for around 250 years since Europeans first arrived in numbers, the cats and foxes that they introduced have been eating their way through the nation’s wildlife. According to one count, 34 Australian mammals have gone extinct since European colonisation. The greatest devastation has taken place in desert regions such as this.

Where once there were bilbies, bettongs, bandicoots and all manner of possums and wallabies, burrows now lie abandoned. Early explorers, among them Ludwig Leichhardt in the 19th century, described many of these species as present in near-plague proportions; his expedition survived almost exclusively off bettongs they killed as the travelling party moved through Australia’s north. Now the animals are gone.

If there’s one creature that tells the story of Newhaven, and of the Australian inland, it’s the mala. The mainland subspecies of the rufous hare-wallaby, the mala (Lagorchestes hirsutus) weighs little more than a kilogram, rarely grows larger than 60 centimetres from nose to tail tip and resembles a kangaroo in miniature. It has a dashing white moustache, shaggy red fur with silver highlights and a tail the colour of sand. Primarily solitary and nocturnal, it seeks refuge from the desert sun in shallow burrows, emerging after dark to feed on leaves and desert grasses. When startled, it explodes from its hiding place and bounds away in frenetic zig–zags.

According to the Warlpiri, the first mala to hop upon the Earth emerged from a series of holes in the ground close to Newhaven’s southern boundary, not far from here. This occurred during the Dreaming or Dreamtime – what Warlpiri and other desert peoples call tjukurpa – when the Earth and its creatures were being created. From there, it fanned out across the desert, following paths that later became the mala songlines.

Stephen Connor, a Warlpiri elder and custodian of the mala songline, will later tell me: ‘The mala’s story begins at Newhaven. The songline follows where the mala went after it came out of the Earth. One branch of the songline goes south to Uluru. Another goes north, along the Tanami Track. That’s my country. My parents and grandparents used to see mala there all the time. I’ve never seen a mala, but we still look after the songline. We go to the sacred sites to carry out our ceremonies with our songs and our stories.’

From the mala’s emergence until sometime around the middle of the 20th century, it ranged across the Australian interior with few cares beyond natural predators, such as dingoes, or the fires that swept across their corner of the country. ‘When people were living traditionally on the land,’ says Steve Eldridge, manager of the Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC) reserve of Ngalurrtju, ‘they used fire as one of their main tools to stimulate growth, which brought in food – kangaroos, that sort of thing. Because they were such a nomadic nation of people, they were moving through the landscape constantly, always lighting fires. A lot of the native flora and fauna adapted to that regime.’

When the Warlpiri and others were driven from their land, summer fires instead burned out of control, wiping out everything in their path. This included any form of cover that sheltered small animals such as the mala, thereby making it easier for predators to pick off the survivors. Not so much a perfect storm as an apocalypse.

‘There were lots of mala out in the bush,’ says Alice Nampitjinpa Henwood, a Warlpiri elder and ranger employed by the AWC, which oversees Newhaven. ‘We used to hunt them. We’d follow the tracks to their burrows and pull them out. Sometimes people burned the country, then hunted them with spears.’

By the 1970s, the mala was in trouble, and not because of Indigenous hunting. In the end, just two isolated mala populations remained. In 1980, five wild mala were taken as the seeds for a captive breeding programme at Alice Springs Desert Park. Some captive-bred mala were released back into the wild, but they were quickly eaten by cats and foxes. In 1986, a predator-free, one-square-kilometre ‘Mala Paddock’ was established in a remote corner of the Tanami Desert. Surrounded by an electric fence, it protected a population of released mala. But foxes, cats and wildfires killed the last wild mala and the species was officially declared extinct in the wild.

The Warlpiri knew of the mala’s demise long before the scientists. ‘For a long time, we didn’t see any mala,’ says Nampitjinpa Henwood. ‘Too many pussy cats. Now the mala are all gone.’

I’ve always been drawn to the tragic symmetry of such stories, of mythological origins and last rites written upon the same terrain, the land marked by a closed circle of birth and death. Such stories give a land meaning and depth. For days, I roam Newhaven, listening into the silence for echoes of the past, heading out from Newhaven’s pretty campground around dawn each morning and returning after sunset. Bright green budgerigars murmur through the trees like a fast-moving, shape-shifting school of fish underwater, mobbing hawks. Winds roar through the desert oaks with a sound that could be a road train. Old-growth spinifex is dotted across salt pans fringed with eucalypts and over red sand hills.

Out in Newhaven’s west – past the thin skeleton of cattle yards and water tanks of Mount Gurner Homestead, abandoned since the 1980s – a barely discernible track leads to Kapuka, a secluded salt pan with a small circle of water, the last remnant of a recent, fleeting storm. As the Warlpiri tell it, Kapuka is a waystation along the mala songline, a place where the first mala to journey north stopped before continuing on its way. I pull over to the edge of the pan and, in complete silence save for the crunch of my boots on firm sand, walk in all directions, skirting signs of snake and goanna, emu and dingo, mulgara and crow. The feathers of pink cockatoos cling to acacias.

But at this site of great significance for the species, there’s no sign of mala. For most species, going extinct in the wild would be the end of the story. But for once, the circle wasn’t closed. When the last wild mala died in the Tanami Desert, there remained mala in captivity, not in the mala paddock, which was discontinued after a fox entered and killed 50 mala in a single night, but at various enclosures across inland Australia. In 2014, AWC reintroduced some of the captive-born malas into its own mala paddock.

While the mala became accustomed to their new surroundings, Alice Nampitjinpa Henwood, her daughter Christine, and a handful of other rangers hunted and cleared feral cats from an adjacent block of land. That task complete, in 2018, AWC put a predator-proof fence around a 94.5-square kilometre exclosure, then the largest of its kind in Australia. Then they released the mala inside the fence.

A mala’s home range is likely less than one square kilometre, which means that these mala are the closest the species has been to surviving in the wild for nearly half a century. That they do so close to where it’s believed the mala first emerged onto the Earth pleases me greatly. It’s also a rare conservation success story that combines, on an equal footing, modern science with ancient knowledge and storytelling. For once, the circle has been reopened and even extended to allow for birth, death and, now, rebirth.

I long to see a wild mala, and on my last night at Newhaven, a small team of AWC scientists takes me into the exclosure after dark.

For the first time in a lifetime spent exploring the Australian wild, I see the bush as it once was. Being here is like stepping back 250 years, to the time before Europeans and their pests arrived. The undergrowth and the grasslands are alive with creatures scurrying about in the darkness. Golden bandicoots, burrowing and brush-tailed bettongs and greater bilbies are everywhere: they, too, have been translocated into the exclosure by AWC rangers and scientists.

And yes, there are mala. They hop along the dirt road, zig-zagging away from the light. In the exclosure, the mala is doing extraordinarily well. There are so many of them that it becomes clear that the mala can thrive out here, if they can live without cats and foxes. ‘This is what the desert looked like when I was a little girl,’ says Alice Nampitjinpa Henwood. ‘The country is healthy again.’

The visit is a privilege, one not yet available to the average visitor who must, for now, content themselves with the raw beauty of an ancient landscape animated by stories and by the promise of more. It’s nonetheless possible to drive around the perimeter of the fenced area, hoping to catch a glimpse.

But if all goes well, my all-too-brief foray inside the fence may well become a vision of a future that plays out across the Australian outback. Until then, the mala has become a living symbol of the renewal of the bush, both a bridge to the past and a hopeful sign for the future. Most importantly of all, the mala is back home, back where it came from and where it belongs.