The world’s drinking water supply is at risk and desalination plants are set to make more saltwater potable. But to make the process sustainable and affordable, new and improved technologies need to be further developed

by Roman Goergen

It was the end of a fight that lasted for almost a decade. On 12 May 2022, the California Coastal Commission, which has a legal mandate to protect the coastline of the US state, voted to deny the building permit for a large seawater-desalination plant that was proposed to be erected near Huntington Beach. Ever since the application to build the plant was made in 2013, this mega-project has been dividing experts, politicians and activists. The southwest of the USA, and California in particular, has been plagued for decades by a devastating drought – the worst in some 1,200 years, according to meteorologists. The levels of water reservoirs in the sunshine state are at record lows, and in April, millions of southern Californians were placed under drastic water restrictions.

Proponents of the desalination project, including California’s governor, Gavin Newsom, would have enthusiastically welcomed the 190 million litres of drinking water the plant would have generated every day. But according to activists, the environment would pay a hefty price. ‘The project would also kill marine life in about 275 million gallons [more than one billion litres] of seawater per day,’ environmental scientist and commission member Tom Luster said before the vote.

The arguments being made in the debate in California mirror similar concerns about desalination around the globe. Global warming and the increasing frequency of droughts in regions that once enjoyed mild climates have led experts to make an alarming prognosis: by as early as 2030, there will be a 40 per cent deficit between demand for, and supply of, drinking water worldwide. Most of these experts say that desalination is the only currently available technology capable of countering such a crisis, but it undoubtedly comes with downsides. Apart from concerns for the environment and marine life, there are issues with regard to cost and efficiency – but there is hope on the horizon.

Water crisis

The term ‘water shortage’ is defined by the UN as a situation in which there isn’t sufficient access to drinking water to fulfil human needs. The World Health Organisation (WHO) states that in times of crisis, every person needs guaranteed access to at least 15 litres of water per day – preferably all drinking water; at least fresh water. According to the World Water Institute, almost two billion people in 17 countries are heading straight for an acute water crisis in the coming years. This will lead to between 24 and 700 million people being displaced by as early as 2040, the UN has warned.

‘Water is among the top five global risks in terms of impacts, reaching far beyond socio-economic and environmental challenges and impacting livelihoods and well-being of the people,’ says Manzoor Qadir, an environmental scientist who focuses on water recycling and safe reuse at the United Nations University in Hamilton, Canada. In a recent study, Qadir and his colleagues concluded that ‘statistics demonstrate that “conventional” sources of water such as rainfall, snow-melt and river runoff captured in lakes, rivers and aquifers are no longer sufficient to meet human demands in water-scarce areas’. Qadir is calling for more desalination plants. ‘Desalination can extend water supplies beyond what is available from the hydrological cycle, providing an “unlimited”, climate-independent and steady supply of potable water,’ he says.

By definition, drinking water should have a salt content of no more than 0.01 per cent. The term ‘fresh water’ is used for a salt content of up to 0.05 per cent, while most crops can tolerate a salt content of up to 0.2 per cent. Even though 70 per cent of our planet’s surface is water, only 2.5 of that can be defined as fresh or drinking water, and 70 per cent isn’t accessible – trapped, for instance, in polar ice. What remains is less than one per cent. Half of the world’s groundwater is either too contaminated with other substances or too saline to be suitable for drinking without treatment. This so-called brackish water has a salt content of between 0.05 and three per cent. For all of these different types of water, the same basic formula applies: the higher the percentage of salt, the more difficult, damaging and energy consuming becomes the process of desalination – at least for those technologies currently in use in significant enough numbers.

High energy cost

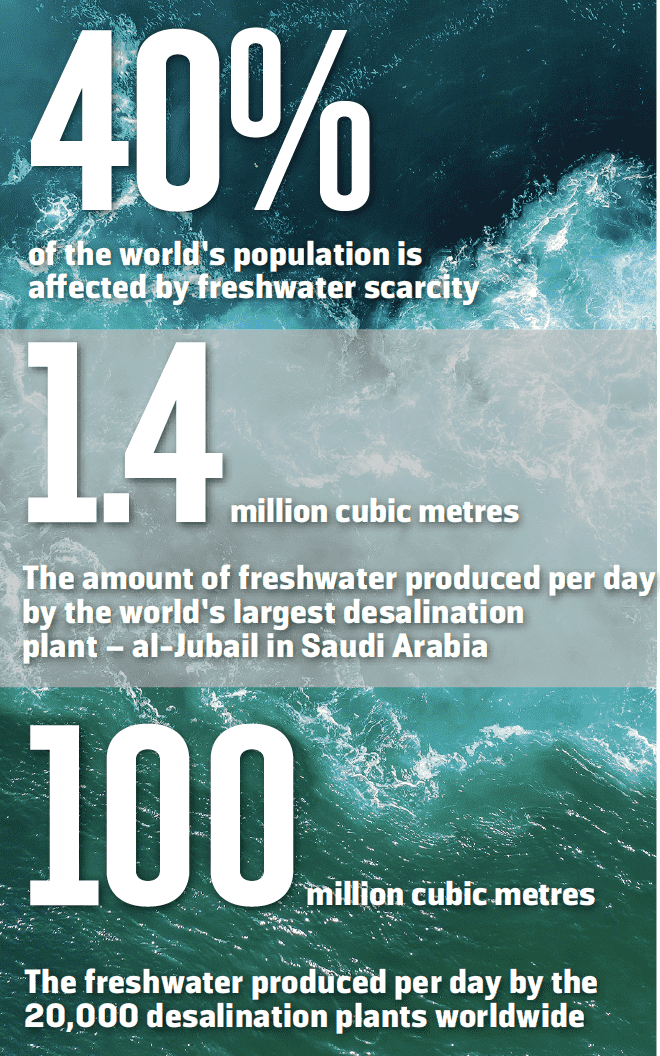

Desalination can work for both the treatment of seawater at coastlines and for clearing up brackish water inland. However, practical obstacles, especially in connection with the process’s waste product, have so far led to a strong preference for erecting plants close to the coast. The Germany-based Desalination Institute (DME), a world-leading think tank for collecting data and offering advice on all things desalination, has counted more than 20,000 desalination plants that produce a combined total of more than 100 million cubic metres of drinking water per day.

According to DME CEO Claus Mertes, the desalination market has been growing by about 15 per cent per year. ‘At the moment, more than half a billion people receive their daily drinking water by means of desalination,’ he says. It sounds an ideal solution and for some nations it has worked well. But desalination comes with significant costs, both in terms of energy use (which makes it expensive) and when it comes to the environment. To supply even more people, experts agree that both environmental and efficiency concerns need to be addressed.

Up until now, water shortages have mostly occurred in regions with high temperatures and lots of sunshine. The biggest desalination plants are located in rich Middle Eastern countries: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the UAE and Qatar currently produce about half of the world’s desalinated water. Using this water for agriculture is prohibitively expensive, so these nations supply drinking water but import food.

What makes desalination so expensive is the energy required to power the different technologies. Currently, most of the world’s desalination plants use one of two methods: thermal desalination (distillation) or reverse osmosis. The former, which has been in use for longer, involves evaporating saltwater and then condensing the water vapour, leaving the salt behind. Most thermal desalination plants utilise waste heat from power plants to heat up seawater or brackish water. The heated water then evaporates in a vacuum and the steam condenses on pipes that contain a cooling liquid. This method is becoming less popular, but remains significant across the Arab world.

‘These types of plants require an enormous amount of energy to take the salt out of the seawater. That’s why energy-rich countries have the advantage,’ says Süleyman Yüce, a chemical reaction engineering expert at RWTH Aachen University in Germany. He adds that the energy cost represents between 40 and 50 per cent of the entire production cost of these plants, depending on which technology is being used and the age of the plant. ‘Therefore, reducing energy consumption is also the most sensible way to make desalination more cost efficient.’

Experts and activists point to a vicious cycle: droughts and water shortage increase the need for desalination, but if desalination uses fossil fuels, the burning of these fuels increases the emissions responsible for climate change. ‘This is one of the reasons why most of the world prefers reverse osmosis for desalination nowadays –about 80 per cent of all plants. But it will still take some time until the remaining 20 per cent of thermal plants disappear,’ says Mertes.

Reverse osmosis operates by pushing saltwater under high pressure through a semi-permeable membrane whose pores are too small for the salt molecules to pass through. From the point when its advantages were scientifically and practically established, it still took reverse osmosis about three decades to overtake thermal desalination as the market-leading technology.

‘Back then, the energy demand for reverse osmosis was 15–20 kWh/m³. Today, we’re down to 3.5–4.5 kWh/m³,’ says Mertes. This energy comes from electricity, so a plant’s sustainability depends on how that electricity is being generated. Generally speaking, osmosis has a lower energy demand, but the higher the salinity of the original water, the higher the cost. Higher salinity causes a higher osmotic pressure in the saltwater, which means more pressure is needed to push the water through the membrane. Engineers have managed to reduce these costs by about two-thirds by developing more sophisticated membranes.

Rohit Karnik is an expert in mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Along with his colleagues, he works with membranes made using a material called graphene. ‘Graphene is a two-dimensional, one-atom-thick material made of carbon atoms,’ he explains. ‘It has high mechanical strength, good chemical resistance and is impermeable to ions and molecules in its pristine state, which opens up the possibility of making membranes by poking selective holes in the material that would allow only water to pass through.’

And yet, despite improvements, reverse osmosis has a physical limitation that puts the method at a disadvantage compared with some of the even newer technologies now being developed. ‘The theoretical minimum of energy required for this method is 1.9 kWh/m³. That is the physical limit – it will never get any better than that,’ says Mertes.

Desalination nations

• The Middle East: Saudi Arabia is the leading desalination country by volume, followed by the UAE. According to the World Resources Institute’s list of the world’s most water-stressed countries (where demand for water is higher than the amount available), Saudi Arabia sits in ninth place, with the UAE sixth. Other wealthy Arab countries, including Bahrain (the most water-stressed nation on Earth), Kuwait (in second place) and Qatar (in third place) also rely heavily

on the technology.

• Australia: When the Millennium Drought gripped southeastern Australia between the late 1990s and 2009, water storage systems in the region dropped to a fraction of their total capacity. Perth, Melbourne and other cities embarked on a desalination-plant spree. The plant in Melbourne, which provided its first water in 2017, now covers a third of the city’s supply.

• Israel: With five large desalination plants and plans for five more, more than half of the country’s drinking water was originally seawater from the Mediterranean.

• USA: There are more than 400 municipal desalination micro-plants in the USA, mostly in California, Texas and Florida. Most are situated close to natural gas facilities in order to exploit the residual heat from the power plants. Although desalination is controversial, enthusiasm hasn’t completely waned.

Waste water

The other big problem with desalination lies in its waste product. Worldwide, plants generate 160 million cubic metres of a hypersaline concentrate per day. This brine is one of the main problems for desalination and a puzzle that scientists have been trying to solve for decades. Producing a litre of drinking water creates 1.6 litres of salty brine and activists are concerned about the byproduct’s effect on the environment, especially marine ecosystems – a concern that was one of the reasons why the plant in Huntington Beach wasn’t approved.

Waste brine is commonly mixed with seawater to a lower salt concentration and then pumped back into the ocean. This kind of waste management is affordable. All that’s required is a pumping system that’s capable of sending the brine back into the ocean. The amount of energy required to pump the brine back depends on its salinity and the plant’s distance from the ocean – which is why there aren’t many desalination plants designed to cleanse brackish water inland.

But environmental activists are concerned about the effects on fragile maritime ecosystems. The high level of salinity alone can damage seagrass beds and fish larvae. The brine can also cause a lack of oxygen in certain layers of the ocean, which could be dangerous to larger marine fauna. In addition, the pumps can hurt or even kill fish and mammals when they suck in water. ‘These plants contribute to climate change, destroy fragile coastal ecosystems, and salt being introduced into the environment poses a risk as well,’ says Fabienne McLellan of the international environmental group Ocean Care.

According to plant operators, if the process is correctly conducted, after the concentrated brine has been mixed down, the same quantity of salt that has been taken out of the ocean is pumped back. But even proponents of desalination have to admit that there are even more problematic pollutants in that brine. ‘In order to operate these plants, and to keep their different mechanical parts functional for as long as possible, chemical additives are being used,’ says Mertes. These can include antifouling agents, descalers or anti-foaming agents. In order to mitigate the various environmental effects, operators in California have developed a trade-off deal, supporting and financing the regeneration of wetlands to make up for the damage caused around their plants.

Scientific progress

Today, these high-energy systems with a worrying waste product may work for water-stressed but wealthy states, but they don’t offer a solution for poorer nations facing water crises, such as Yemen or Somalia. There, NGOs and others are working on smaller, less cost-intensive desalination projects, often replacing fossil fuels with solar power to keep the plants running.

Meanwhile, scientists are working on technological solutions that could solve both the environmental issues and the energy-efficiency problems. ‘Researchers are currently working on more than 50 desalination technologies that are, in parts, so fundamentally diverse, that they follow different disciplines of the natural sciences,’ says Mertes. He’s convinced that one day, some of these technologies will replace reverse osmosis, although he accepts it will take a long time for new plants to come online.

As different as each new idea is, Mertes points to a common denominator – something that he describes as a paradigm shift when it comes to the underlying idea of how desalination is supposed to work. ‘In the past, we were too focused on attempting to squeeze fresh water out of the salt water,’ says Mertes. Now, he says that new technologies aim to directly remove salt and solids, which amount to about three per cent of the volume of seawater.

A technology called capacitive deionisation appears to be particularly promising. Here an electrostatically charged surface is submerged in saltwater. The static causes the salt ions to attach themselves to porous electrodes, often made from carbon. When the surface is lifted from the water, the salt can be released by changing the polarity of the electrodes. ‘[It’s] just as if you had some kind of electrostatic shovel,’ says Mertes.

Currently, the main issue is that the ‘shovel’ needs to unload the salt ions regularly, so the process has to be repeatedly interrupted. To improve on that, scientists at RWTH Aachen University have developed a variation of the process – called flow-electrode capacitive deionisation – that uses a liquid suspension rather than a solid surface, so the metaphorical shovel doesn’t need to be unloaded.

Other methods that promise to offer stand-alone desalination in the future are currently being trialled as complementary processes in reverse osmosis plants. At Columbia University in New York, scientists have developed a solvent-based extraction method called TSSE. Saltwater is combined with a liquid solvent and vigorously shaken. The salt separates from the mixture, which, when heated, separates further into solvent, salt and drinking water. The method ‘uses a solvent that acts like a “sponge”, soaking up just the water but not the dissolved salt. Warming up the solvent is analogous to squeezing the sponge to release the water,’ explains Ngai Yin Yip, professor of earth and environmental engineering at Columbia.

The method doesn’t require membranes or the high temperatures needed for distillation, can be powered by renewable energies and is generally more cost-efficient. ‘Using reverse osmosis, when there is too much salt, the pressure needed is too high for the membrane to sustain and therefore reverse osmosis is restricted to seawater salt concentrations and below. TSSE doesn’t have such a limitation and can desalinate more salty water,’ explains Yip. At this stage, TSSE can help to reduce the environmental burden of reverse osmosis plants by cleaning up the high-saline-brine waste product.

According to Yip, TSSE has made tremendous progress in the past two years. His team has demonstrated that the technology can extract all of the water from the brine and achieve what the industry calls ‘zero liquid discharge (ZLD)’, where all of the water in the brine is converted to desalinated water and only solid minerals of the salt are left behind.

‘This is a hugely significant development. Current methods to obtain ZLD are all very energy intensive and costly,’ Yip says. He’s confident that TSSE will be the answer to many of the environmental questions that are still posed by desalination naysayers.

Desalination in Africa

Much of Africa faces a water problem. Droughts are predicted to intensify in semi-arid regions such as the Western Cape of South Africa, as well as in North Africa. Even in wetter countries such as Nigeria, many water resources are polluted. North African governments in particular are bulking up their desalination capacity. The government of Algeria is implementing a new emergency plan that will focus on seawater desalination for its drinking water supply. Tunisia is ramping up production of multi-million-dollar facilities and Egypt’s sovereign wealth fund is building financial partnerships of up to US$2.5 billion to build, own and operate 17 new solar-powered plants by 2025. It eventually aims to supply 6.4 million tons of water per day through desalination plants drawing on seawater by 2050. And while previous plants were used only for drinking water, they are increasingly being built to cater for irrigation. A plant recently completed in Agadir, Morocco, was designed partly for this purpose.

Irrigation is also on Egypt’s mind. The country is currently building new cities outside of the Nile Valley and will rely on desalination to do so. Due to concerns about the reliability of the Nile River, partly prompted by the building of Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, the country is keen to become less dependent on the river for its water needs.

In poorer countries, some smaller desalination plants provide assistance, but, by and large, cost and energy requirements still mean significant projects are reserved for richer nations.

Moving forwards

And yet, while scientists are making significant leaps forward, no matter which new desalination technology is under review, all experts emphasise that the market changes slowly. ‘These processes take decades,’ stresses Yüce. The breakthrough discoveries concerning reverse osmosis membrane technology were made during the 1960s – yet the number of reverse osmosis plants only overtook thermal plants during the 1990s.

‘It takes time to convince clients – for instance water suppliers – that a new technology is efficient and safe,’ says Mertes.

The war in Ukraine may speed up some developments. Operators of desalination plants using fossil fuels are becoming increasingly concerned about energy prices. Yüce noticed an increased demand for renewable energies, especially solar, even before the war started. He points in particular to Israel, a world-leading desalination player that has been using fossil fuels for its plants for a considerable length of time. ‘Israel has purchased these fuels on markets that now experience a much more increased demand due to the war in Ukraine’, says Yüce. The country is now looking for more solar power to secure its water supply. Last year, it entered into a deal with water-stressed but sun-rich Jordan, in which Jordan would export 600 megawatts of solar power to Israel and in return receive 200 million cubic metres of desalinated water. Water and energy shortages appear to be bringing even political opponents to the negotiating table. War and climate crises may accelerate the changing of the guard, even in the conservative desalination market.