As India’s controversial National River Linking Project goes ahead, new research reveals it could disrupt monsoons

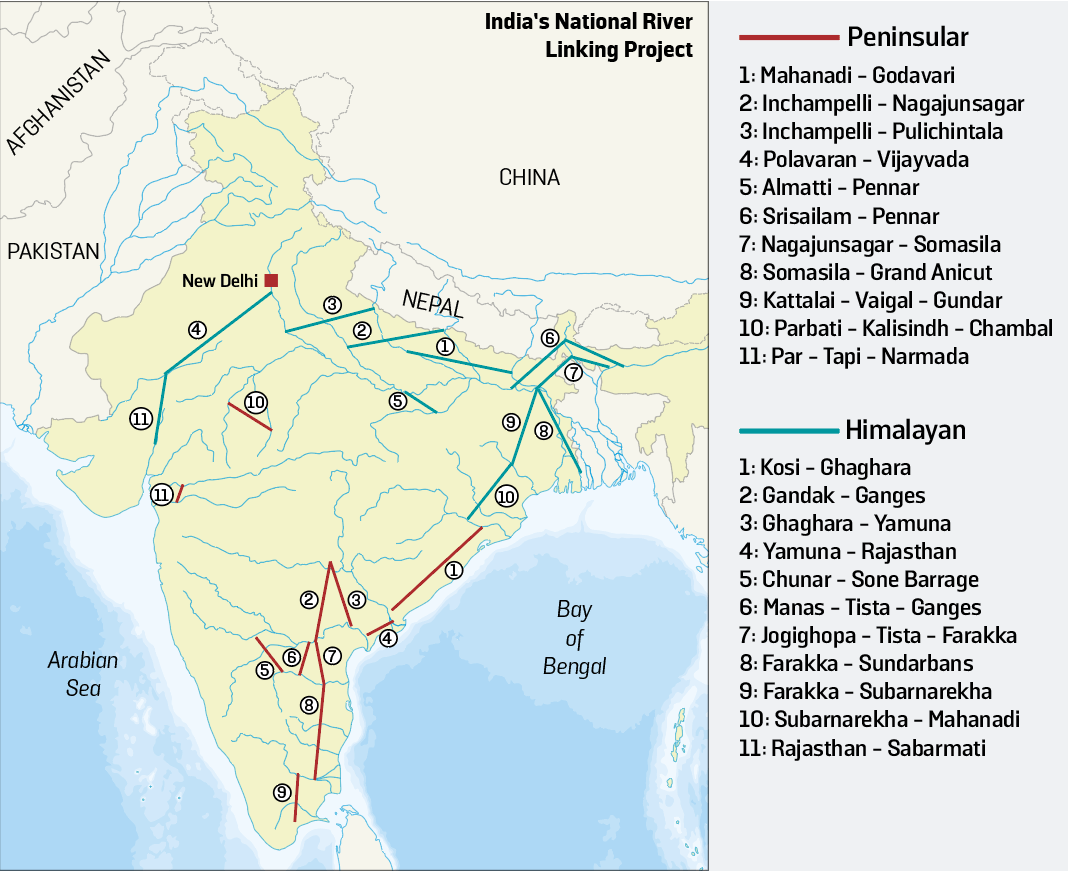

In October, India’s ambitious scheme to build a 230-kilometre canal between the Ken and Betwa rivers was finally approved. It’s the first of many projects planned for implementation under the National River Linking Project (NRLP), which aims to connect 37 Himalayan and peninsular rivers across the country via some 3,000 reservoirs and 15,000 kilometres of dams and canals. The government has touted the NRLP, which was first mooted more than four decades ago, as the solution to drought-proofing the country. But new research suggests the US$168 billion project could actually make the drought worse.

India’s average annual surface water run-off is about 1869 billion cubic metres, which should be more than sufficient to meet the country’s rising water demands – a significant portion of which is designated for agriculture. However, most of this water arrives during the monsoon season, between June and September, and an estimated 60 per cent of the rainfall drains directly into the oceans. As such, just 37 per cent of surface water can currently be used.

The goal of the NRLP is to annually divert as much as 174 billion cubic metres of this ‘surplus’ water from the Brahmaputra and lower Ganga basins in eastern India to the parched river basins of western and central India where it can be stored. According to the National Water Development Authority, which is overlooking the project, this would provide irrigation for an additional 35 million hectares of land. However, researchers at the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, say that the impact of moving such vast volumes of water could have unintended impacts on the atmospheric feedback loops that regulate evapotranspiration and precipitation.

‘As the river-interlinking projects aim to utilise most of the surface water for irrigation, it will increase evapotranspiration over previously unirrigated regions and change the land-atmosphere feedback and recycled rainfall over India,’ explains Matthew Koll Roxy, a climate scientist and co-author of the study. Essentially, as the additional surface water evaporates and cools, it could cause fluctuations in temperature across different land regions and in neighbouring basins, changing wind patterns and, as such, the movement of clouds and location of rainfall.

Roxy cautions that large-scale river interlinking could alter rainfall patterns during the Indian monsoon, reducing September rainfall in the country’s driest regions by up to 12 per cent. ‘The reduction in September precipitation will dry up the rivers in the subsequent months, amplifying water stress manifolds in various parts of the country,’ the study’s authors report.

Moreover, instead of distributing moisture equally across all basins, the study suggests that the project could create greater imbalances. ‘While river interlinking can potentially lead to a reduction in precipitation in arid regions of the country, it can also lead to an increase in rainfall of up to 10 per cent in some parts of the Ganga, Godavari, and Krishna basins,’ says Roxy.

Ever since it was first proposed, India’s interlinking of rivers project has been fraught with controversy, causing disagreements among its many stakeholders. As part of the Ken-Betwa interlinking project, government documents indicate that around 6,809 hectares of forest land will need to be cleared. An estimated 10 per cent of the Panna Tiger Reserve, a fragile deciduous forest that forms a critical habitat in northern Madhya Pradesh for endangered tigers, stands to be submerged.

Environmentalists and activists have repeatedly raised concerns about the potential impacts to aquatic ecosystems from the introduction of non-native, invasive species throughout the NRLP. In 2017, US scientists warned that ‘moving even slightly away from the natural flow regime (the recorded historical pattern of floods and droughts) can lead to a collapse in the structure of ecological networks’ and, in 2011, researchers found that any interlinking project could cause lasting changes in the aquatic system and fish diversity.

In 2018, researchers at the University of Colorado also discovered that river interlinking could decrease silt deposition in the Ganga and Brahmaputra deltas by 30 per cent, making the area more vulnerable to sea level rise and coastal erosion. It estimated that discharge from 24 out of 29 rivers assessed would decrease, which ‘may damage wetlands and contribute to the deterioration of freshwater and estuarine ecosystems.’ According to researchers at the Indian Institute of Technology, these findings give enough reason to seriously question the benefits of river interlinking. Roxy emphasises the importance of evaluating the many potential and unknown impacts before any more work goes ahead.