Scientists and businesses are convinced that farming insects could help provide the world’s growing population with food while lowering carbon emissions

By

Peter Morris opens a sturdy industrial door and a few stray locusts hop out of the way as he strides down the corridor. They’re escapees, but that’s not a huge concern to the team here at Monkfield Nutrition, a company tucked away in rural Cambridgeshire. The reason why becomes obvious as soon as the next door is opened.

‘They’re plenty of insects in here,’ says Morris, a production manager for the company. ‘They’re swarm insects, so that helps to stimulate breeding.’ Behind the door, cages upon cages of chirruping yellow locusts fill the space, warmed to their preferred desert temperature. Clinging to the mesh of their cages in their thousands, these breeding adults are just a fraction of the four million insects produced at Monkfield every year.

Once the shock of this biblical scene resides, a closer look at the front of the cages reveals waiting pots. ‘Females come to the egg pot, they sit on it, put their ovipositer into it and then lay their eggs,’ Morris explains. The eggs are carried off to another room where they are incubated and then moved to the hatching room. All in all, 65 rooms here contain locusts or crickets at every stage of their development, from minuscule newborns no bigger than pinpricks to fully-grown breeding adults. To produce the latter, it takes about 35 days.

At the moment, most of these critters will end their lives in the stomachs of reptiles. Monkfield is a supplier of lizards, snakes and spiders for the pet market and also sells live food in the form of bugs. But Monkfield CEO, Jo Wise, is now banking on the expansion of a very different market. ‘I started thinking about insects for human food about five years ago,’ he explains, back in his office away from the whir of crickets. ‘We had to relocate in 2018 and we’ve got far greater capacity on this site. So we took the plunge.’

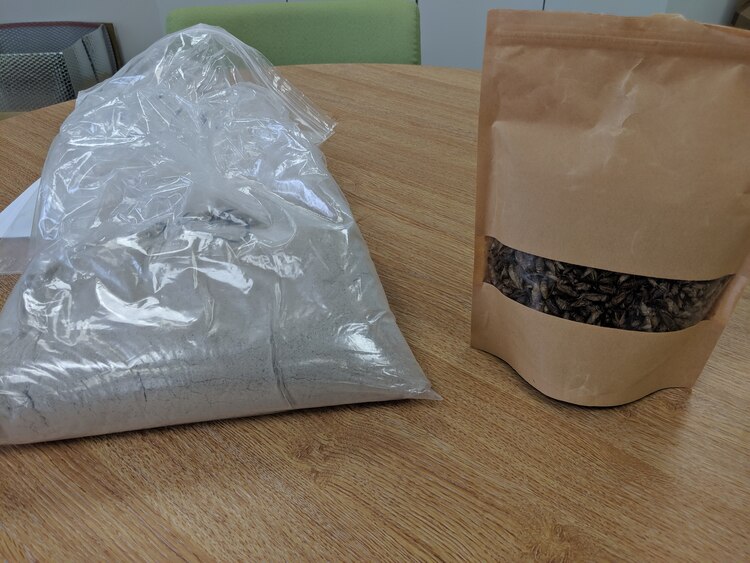

So far, Wise’s production for humans is still limited. He has equipment to dry whole crickets and a mill with which to crush them into cricket flour (crickets are more appropriate for human food than locusts) and the company now sells both of these human-grade products on a small scale. But he, like many others, thinks there’s plenty of room for expansion.

Emerging market

In some Asian, African and central American countries, insects have been consumed by humans for millennia. Though these processes are rarely industrialised or carried out on a large scale, the number of people eating insects is still huge. It’s seemingly only the West that harbours a real aversion to the idea – though this might be changing.

In the UK, the market for insects as human food is very limited, but gradually growing. A company called EatGrub sells flavoured edible crickets and protein bars spiked with cricket flour in around 250 Sainsbury’s stores. London-based restaurant Archipelago will whip you up caramel mealworms with blinis and vodka jelly, while in Pembrokeshire, the BugFarm serves bug-based meals in its somewhat famous café.

In some European countries, along with the US and Canada, a couple of larger companies operate in the edible insect space, including Dutch agri-tech company Protifarm, which produces a tofu-like ingredient made from the buffalo beetle, and French-based Jiminis, whose insect-enriched pastas, bars and granola products are available in 650 of the country’s Carrefour supermarkets.

Investment news is also promising for insect-enthusiasts. Lux Research publishes an annual list of the ‘top 20 technologies predicted to transform the world’ and next-generation protein (including insects) came in at number five in 2019. The accompanying report states that the industry received five times the investment in 2019 compared to the previous year, landing more than $200million. Nevertheless, back in the shops, there’s no sign of bugs becoming a dinner staple just yet.

Why eat bugs?

A number of researchers, campaign groups and entrepreneurs are working to change this perception problem, and not just because they think insects make a tasty snack. As research has increased in this area, a range of scientific papers has begun to point to insects as being a sustainable form of protein, one that could help provide nutrition for the world’s ever-increasing human population, while avoiding some of the damaging consequences of intensive farming.

The data varies according to the type of insect and the place and way it is farmed, but some benefits are universal – the key one being that insects are much more efficient at converting feed into protein, meaning they need less food to produce the same nutritional content as other animals. According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), crickets need 12 times less feed than cattle, four times less feed than sheep, and half as much feed as either pigs or chickens to produce the same amount of protein. In addition, Protifarm claims that crickets contain similar amounts of vitamins b1, b2 and b12 as beef and similar amounts of omega 3 and 6 to fish.

If bugs are full of nutrients, they are also less demanding on the environment. Insects are reported to emit fewer greenhouse gases and less ammonia than cattle or pigs, and they require significantly less land and water than livestock or other protein sources such as soybeans. The FAO also notes that insects could potentially be fed on organic waste streams, enabling them to contribute to a circular economy. It is this in particular that excites many people in the field.

‘One of the things that I initially liked about insects, and that I think is still a major value, is that they can be fed on all manner of different organic material,’ says Nick Rousseau, managing director of the Woven Network, a UK-based association connecting people involved in the insect industry. ‘They can be very good at converting whiskey by-products or cauliflowers or potato peelings into protein. That’s their real strength.’ All of which could prove useful in a world where 30 per cent of food is wasted – an amount which contributes around 3.3 gigatons of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere – ten per cent of all of all global carbon emissions.

The ick factor

However, it is all well and good extolling the benefits of eating insects, but the question remains – is anyone willing to actually do so? Despite the fact that an estimated 2.5 billion people regularly consume them – mostly in tropical countries – the response of people in the West still seems to be one of disgust. Insect enthusiasts think this can change, particularly as more products start to incorporate insects in a hidden way, as a paste or a flour.

‘We see the potential for insects being more normalised as a generational shift,’ says one of these enthusiasts, Robert Nathan Allen, the founder of LittleHerds, an educational non-profit organisation based in Texas that seeks to educate people about the benefits of edible insects. ‘Over the first couple of years here in Austin, we very quickly realised that kids don’t have that psychological taboo entrenched the way that adults do. They’re not as reticent. And some of the research that’s been done in places such as the Nordics, the UK and the US, certainly does show that younger consumers, millennials, Gen Z, and even younger generations are more open to new experiences, new traditions and are looking for products that meet their particular values.’

Like many people in the field he points to the example of sushi as a foodstuff that has undergone a radical transformation when it comes to Western consumer perspectives. While raw fish was once considered unsafe and unclean, it eventually moved from luxury to staple. ‘I see the normalisation of insects as food as something that will be on the time frame that sushi was – so multiple decades, a generational shift,’ says Allen.

But not everyone is optimistic. Dr Jonas House is a researcher at Wagnerian University in the Netherlands and focuses on dietary change. As part of his research he has investigated public acceptance of insects as food in the Netherlands and the results are less encouraging. ‘When I started my PhD, it coincided with a range of insect-based foods being sold in a supermarket chain in the Netherlands,’ says House. ‘I found that they weren’t really fitting into people’s diets. People are often willing to try stuff just to see what it’s like. But the products were rarely eaten more than once or twice.’

In addition, and crucially from an environmental perspective, House found that the insect products available weren’t standing up as viable meat alternatives. ‘All the evidence gathered showed that in the cases of people who are eating these products, they’re eating them instead of plant-based products, or as well as meat. They’re not replacing meat, as far as I can tell, and that particularly applies to things such as insect-based snack bars. Is that realistically a replacement for someone’s chicken dinner? This is a question that needs to be asked I think.’

Fussy customers

There are also other barriers. Back at Monkfield, Jo Wise explains that producing insects is relatively expensive and that with volumes still low, it is not an easy business to crack. ‘We’re comparable to meat, but ideally we want to drive the cost down as low as we can. If the volume’s not there, it’s quite hard to do that.’ One of his main costs is heat as the insects prefer the warmth, and though he uses a biomass boiler and solar panels, energy costs are still expensive when added to labour costs and feed for the insects.

According to Nick Rousseau, ‘pound for pound a half-kilo of insects will cost you a lot more than a half-kilo of chicken.’ This is largely because insect farming has not yet been automated – something that might change in the future if the market picks up.

In addition, to really boost environmental credentials and create an industry plugged into the circular economy, feeding insects with organic waste (tht is leftover food) is the best approach. However, while Rousseau is excited about this prospect, he also admits that ‘the waste isn’t always there – it can be seasonal or it can have a value depending on what else is around.’ In addition, the EU currently bans insects from being fed with post-consumer waste or catering waste.

Wise also highlights this as an issue. ‘I think if you were to rely on a waste stream for the crickets, you’d have to find a fairly consistent, relatively good quality waste stream. And then when waste has a value like that it ceases to become waste.’ He adds that insects can be picky – it won’t to do feed them any old leftover. Having tried multiple different diets for the crickets over 30 years, he knows that when unsatisfied they will start to eat each other – not ideal from either a cricket or a business perspective.

If that wasn’t bad enough, there are other regulations to deal with. Outside the EU there are still very few restrictions on breeding and selling insects, but in Europe things have recently become harder, much to the chagrin of innovators in the field. In 2018, the EU labelled all insects as ‘novel foods’ meaning that from January 2020 they became subject to ‘Novel Food Regulations’. These regulations mean that in order to sell insects as human food, every new species must now go through a special application process, something Wise says can cost applicants six-figure sums for just one type of cricket. ‘It’s frustrating, because people have been eating insects forever in Asia, so why should we have to categorise them differently to the way Asia, Canada, America or even Norway does? With the market size as small as it is, putting in a six-figure application is a big ask.’

Fish food

As a result of these difficulties, a related market for insects is currently moving much faster – insects being fed to other animals as feed. Most of the really big insect breeders operate in this space, predominantly producing insects as feed for farmed fish. The most popular critter for this purpose is the black fly larvae, a species that can be bred quickly and fed on organic waste in many countries (though not yet the EU).

Jason Drew is the founder of AgriProtein, one of the largest insect-for-feed manufactures. Based in Cape Town, the company has factories all over the world in which it farms black fly larvae. ‘It’s quite an industrialised process,’ he says. ‘We take in just over 90 thousand tonnes of organic waste into each factory and from that make insect-based compost, proteins and oils that go into the animal feed chain.’

Drew is passionate that using insects in this way (something the company refers to as ‘nutrient upcycling’) can become a vital solution to the global food waste problem, and also eliminate one of the main issues with current aquaculture practices – in which fish are fed with other fish, thereby depleting ocean stocks. ‘The world as we see it is long on waste and short on protein,’ he adds. ‘Breaking that cycle seems immensely sensible, particularly if one can do it profitably and provide other benefits in the process.’

Watch this space

Nevertheless, those punting for insects as human food aren’t giving up yet. Drew is insistent that feeding insects to fish and chickens is entirely natural – something these animals have been eating in the wild for millennia. By extension, he views eating insects as being something humans have simply forgotten how to do.‘Westerners who don’t tend to consume insects absolutely adore the insects of the seas – which are shrimp, oysters, mussels and lobsters,’ he says. ‘Those animals also eat detritus and waste. The Western world loves the insects of the sea, they’ve just forgotten that people are only alive today because [ancient] humans used to eat land-based insects too.’

Persuading consumers of this fact may be what it all comes down to. As larger companies in the animal feed space invest heavily in mechanisation, automation, conveyor belts and specialised equipment, smaller breeders looking to move into human food may also benefit from lower costs. But whether they can persuade picky Westerners to consider a wholesale change to their diets remains to be seen.