Geographical in-depth guide to Rwanda

Rwanda’s urban cemeteries are running out of space. Many of the country’s 1,500 cemeteries, having reached capacity, have already been expanded several times to accommodate more graves. In the capital of Kigali, Rusororo, the city’s largest cemetery, is now encroaching on the Nyandungu Urban Wetland, an ecotourism project intended to restore degraded habitat and create green jobs for local communities. Faced with an ever-decreasing availability of suitable land, concerned city officials have called for a new ‘vertical burial system’ – multi-storied tombs – to save space.

It’s not the first time city officials have sought solutions to the shortage of burial plots. In 2013, parliament passed an amendment to the law permitting the practice of cremation, a culturally foreign concept in Rwanda. If Rwanda aspires to have smart and sustainable urban centres, a number of things will have to change, Mugisha Fred, Kigali’s head of urban planning and construction, told Rwanda Today. ‘As we try to free up land for settlement, infrastructure and industry, we need to run smart landfills and cemeteries.’ To date, however, Rwanda has built just one crematorium, the Hindu Mandal Crematorium in Bugesera, a district in south-central Rwanda. Only a handful of cremations have taken place since its construction, and residents appear reluctant to adopt the new practice.

FACT FILE

Area:

Total: 26,338 sq km; Land: 24,668 sq km; Water: 1,670 sq km

Population: 13,623,302

Population growth rate:

1.62% (global rate: 0.91%)

Population density:

546 per sq km of land (global average: 62)

Capital: Kigali;

Population: 1,248,000

Languages (official):

Kinyarwanda 93.2%, French, English, Swahili

Religions:

Christian 95.9%, Muslim 2.1%, other 1%

Overcrowded cemeteries are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the growing problem of Rwanda’s land scarcity. Slightly smaller than Belgium, with a total land area of approximately 26,000 square kilometres, Rwanda is one of the smallest countries in mainland Africa. It’s also one of the most densely populated. Since the 1990s, the country’s population has increased sixfold and currently exceeds 13 million people. This rapid increase has led to a strain on the country’s limited food resources, the demand for much-needed housing and infrastructure, and increasingly threatens the country’s unique biodiversity.

Nowhere is growing faster than Kigali, home to more than half of Rwanda’s urban population. By 2050, it’s thought that 3.8 million people will call the city their home, and finding a housing solution for everyone is proving to be a challenge. In 2013, Singaporean firm Surbana Jurong secured a contract to produce a master plan for Kigali, proposing to replace the existing city with an entirely new vision of a ‘smart’ city filled with high-rise buildings and green infrastructure (the Singaporean developer has become the go-to city planner on the continent, with contracts for seven other major African cities: Kinshasa, Brazzaville, Libreville, Bujumbura, Conakry, Luanda and Lagos).

A POLARISING PRESIDENT

On the last Saturday of every month, Rwandans across the country come together to participate in Umuganda. From 8am, all able-bodied citizens spend three hours sweeping the streets, planting trees, tending to terraces and picking up litter. It’s a practice that stems from the country’s pre-colonial history, when many hands made light work of digging the fields ahead of the rains. In 2009, as part of Rwanda’s post-genocide reconstruction efforts, it was reintroduced by President Paul Kagame as ‘umunsi w’umuganda’ (‘community contribution day’ in the Kinyarwanda language). It’s credited with keeping the country spotlessly clean but, for many, the term is synonymous with forced labour.

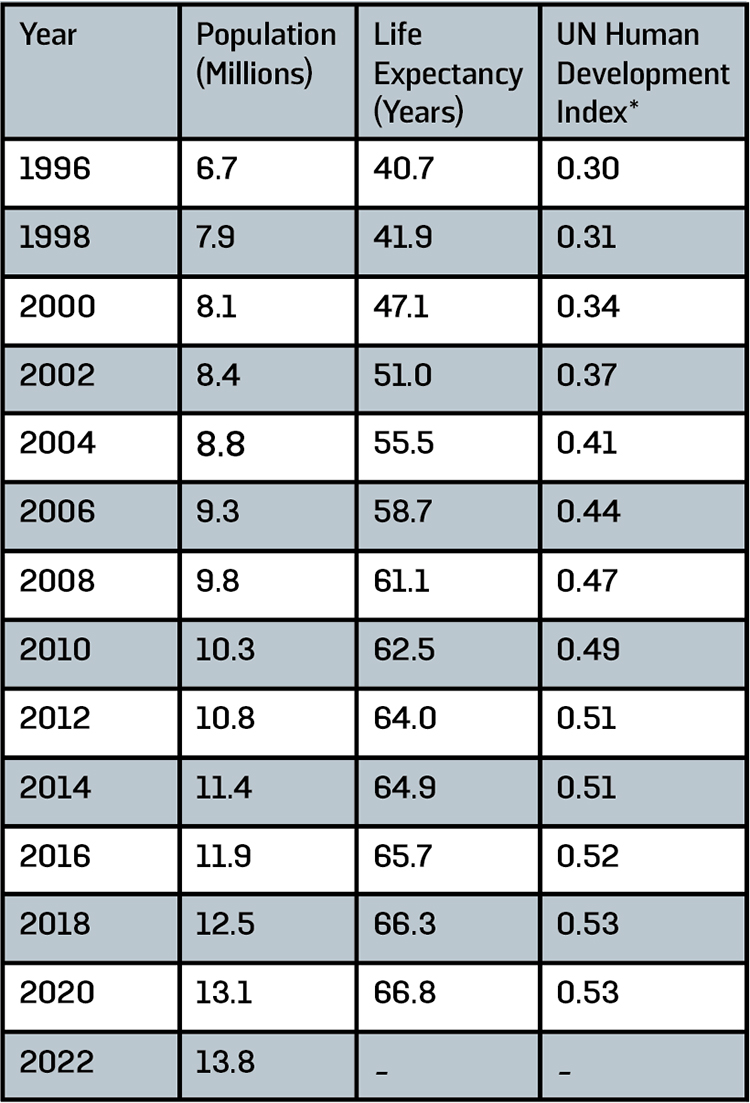

Kagame, 66, has been in power since 1994. In that time, his government’s influence on the country has been transformational. According to the UN, Rwanda’s score on the Human Development Index more than doubled between 1990 and 2017 – the world’s highest average annual growth rate. The economy has grown exponentially, poverty has fallen and primary school enrollment is almost universal. The country’s breakneck progress has earned it the nickname ‘Africa’s Singapore’. Yet critics of Kagame, including political opposition and journalists, face surveillance, intimidation, arbitrary detention and worse. In the election in July this year, Kagame secured a fourth time with more than 99 per cent of the vote, potentially keeping him in power until 2034.

GROWING PAINS

Dimitri Stoelinga, co-founder of Rwanda-based research-consulting firm Laterite, first visited Kigali in 2009. In the time since, he says that the city centre is almost unrecognisable as the same place he moved to some 15 years ago. New roads, hospitals and shopping centres, a new 10,000 seat indoor sports arena and a re-vamped 45,000 seat stadium, and the US$300 million Kigali Convention Centre – as well as whole new neighbourhoods and commercial developments – have popped up on the city’s skyline. ‘I have never seen anything like it,’ says Stoelinga. ‘It is like day and night.’

Importantly, he adds, all this construction is part of a clear development strategy for the city. Rwanda has set its sights on becoming a middle-income country by 2035, a goal it aims to achieve by transforming the nation from an agriculture-based economy to a knowledge and service-based one. In recent decades, government policies have focused on rebuilding and investing in major infrastructure such as energy, transportation, and information and communication technologies.

So far, it’s a plan that seems to be working, albeit perhaps a little too well. Economic migration to Kigali is on the rise and, as rural workers move to the city in search of work, informal settlements on the fringes of the city have grown. Today, an estimated 83 per cent of Kigali’s population still lives in these informal settlements, which occupy 62 per cent of the city’s land.

Anirudh Rajashekar, director of urban-planning research consultancy Jerry-can, explains that Kigali’s informal settlements are characterised by low-quality, overcrowded housing with living conditions that pose a long-term risk to residents’ quality of life. While these informal settlements share some similarities, such as the building materials, some face greater environmental hazards due to their location on steep hillsides or in valleys with limited access. The largest is Bannyahe, an informally built, densely settled neighbourhood located in the low-lying areas close to the city’s marshland, where residents face the threat of deadly floods and landslides caused by heavy rains.

LAND OF A THOUSAND HILLS

Land-locked Rwanda sits at a high altitude at the centre of Africa’s Great lakes region. Its terrain can be pictured as a series of descending steps. The western border is dominated by the Congo Nile Ridge, part of an extensive mountain range bordering the Albertine Rift Valley, which skirts the edge of Lake Kivu. At its northernmost point, the ridge connects with a chain of two active and six extinct volcanoes, five of which form the Virunga Mountains, home of the endangered mountain gorilla and Rwanda’s 160-square-kilometre Volcanoes National Park. At 4,507 metres, the extinct stratovolcano Mount Karisimbi is the country’s highest point.

The elevation drops towards a central plateau that is characterised by rolling hills, aptly giving Rwanda the nickname ‘the land of a thousand hills.’ The capital, Kigali, sits among these gently sloping valleys.

Finally, to the east, the country consists of a mix of low plateaus, swamps and wetlands, including the sprawling Akagera National Park, Central Africa’s largest protected wetland and a refuge for savannah-adapted species such as rhino, hippos and lions.

Rwanda’s national parks are the pride its burgeoning tourism industry, and mountain gorilla trekking in Volcanoes National Park is the undisputed star attraction. In 2021, more than 500,000 visitors to the park brought in US$164 million, an increase of 25 per cent from 2020.

But Rwanda’s protected natural areas offer benefits far beyond tourism revenue; they are central to the country’s sustainable development strategy. Recently, Kigali earmarked US$80 million for the restoration of five surrounding wetlands, part of the government’s focus on building a climate-resilient capital. ‘Urban wetlands play a critical role in preventing flooding, addressing pollution and are home to unique biodiversity,’ says Juliet Kabera, director general of the Rwanda Environment Management Authority. ‘As we face the impacts of climate change, wetlands will be a key ally to protect lives and livelihoods.’

However, in interviews with residents, Shakirah Esmail and Jason Corburn (researchers in urban planning at UC Berkeley) found that life in informal settlements such as Bannyahe has been made all the more precarious by the competing spatial needs of the residents and the preservation of nature.

COMMUNITY MATTERS

In the wake of the 1994 genocide, Rwanda experienced a resurgence of preventable illnesses such as malaria, cholera, tuberculosis and HIV. At the time, less than five per cent of the population had access to clean water, and few clinicians remained in the country to provide much-needed primary care. Today, however, Rwanda has a vaccination rate of 94 per cent, and more than 90 per cent of the population has access to a universal health system that allows the country’s poorest to receive services for free, resulting in drastic improvements in life expectancy and living standards. To achieve this, the government prioritised the training of a network of community health workers to support the country’s overwhelmingly rural population. By 2018, each of Rwanda’s 15,000 villages had four elected community health workers, who have promoted the uptake of vaccinations and ensure that all pregnant women attend antenatal clinics.

One of the most significant outcomes has been a dramatic reduction in child mortality. This, coupled with increased access to family planning services and a growing awareness of birth control methods, has led to a decline in the country’s fertility rates (the average number of births per woman dropped from 5.6 in 2005 to 3.3 in 2022). However, Rwanda’s population remains young, with a median age of 20.8, and the sheer number of people entering childbearing years means a high birth rate will likely continue for some time.

RURAL LIFE

In 2013, in an attempt to address some of the challenges in overpopulated Kigali, the government commissioned Surbana Jurong to work on a new initiative: the Secondary Cities Master Plan. This plan focuses on six strategically chosen cities around the country – Muhanga, Huye, Rusizi, Rubavu, Nyagatare, and Musanze – aiming to transform them into regional economic hubs that will shoulder some of the burden of urbanisation, attracting businesses and residents away from the congested capital. According to Claver Gatete, Rwanda’s minister of infrastructure until 2022, urbanisation is both irreversible and inevitable, and therefore needs to be guided. ‘Rwanda has an ambitious objective of accelerating the urbanisation to a portion of 35 per cent urban population by 2024,’ he adds.

For now, most of the country’s population is rural. The vast majority of Rwandans rely on agriculture for their livelihoods and, despite the country’s economic growth in recent years, most are smallholder subsistence farmers growing beans, sorghum, banana and cassava crops. Nestled amid towering mountains and crisscrossed by valleys Rwanda’s agricultural productivity is also constrained by its geography, limiting the availability of flat, arable land. According to the World Food Programme, a fifth of the population is food insecure. Some farmers cultivate cash crops such as tea, often as contract farmers for commercial enterprises, or have formed cooperatives to collect, wash and sell coffee, Rwanda’s third most exported product (after gold and tin ore).

Historically, land ownership in Rwanda has sidelined women, limiting their control over agricultural resources and decision-making powers. Today, however, a significant shift is underway. In recognition of the vital role women play in the country’s food production and rural development (82 per cent of women are employed in agriculture compared to 63 per cent of men) – and to help prevent conflict caused by land shortages – the Rwandan government set out to formalise and expand land ownership across the country. This included giving women the right to legally own land. In 2016, 63.7 per cent of land titles were registered as owned or co-owned by women. Since then, Rwandan women have continued to take on roles traditionally held by men, and Rwanda is the first country in the world with a female majority (61 per cent) in parliament.

A COMMON IDENTITY

Since Covid-19, Jonathan Beloff has noticed an increasing sense of unity among younger Rwandans. ‘I think that, after social distancing, people were just exciting to come together again.’ Beloff, an expert in the politics and security in the African Great Lakes region, was already aware that the fears of older generations – that ethnic conflict could reemerge – weren’t shared by the country’s youth. This is largely down to the government’s social engineering, a deliberate attempt to erase ethnic divisions under the banner of Ndi Umunyarwanda (‘I am Rwandan’).

Today, Rwanda has a reputation for being the safest and most stable among its neighbouring countries in the Great Lakes region. Beloff accuses the global media of a tendency to look at Rwanda through Western eyes. ‘They look at Kagame and see a dictator, but most Rwandans want the stability he brings to the country. They like what he is doing. They are more concerned about other issues – jobs and housing.

Despite progress, there is still work to be done. Stoelinga admits that not everyone is happy with the way the country is changing, but he’s never seen a city space transform to a plan at such speed. ‘At the current pace of change, it’s really hard to predict where things will go,’ he adds. ‘Who knows what Kigali is going to look like in ten years time.’

TIMELINE

1300-1800s

Arrival of Tutsi cattle herders in Rwanda, which was already inhabited by the Hutu and Twa peoples, and the establishment of a hierarchical social system with a Tutsi monarchy. Land ownership is concentrated among the Tutsi elite (14% of population), while the Hutu majority (85%) become agriculturalists on the land they managed, and the marginalised Twa (1%) are hunter-gatherers.

1885

European powers partition Africa, assigning Rwanda to German control.

1900s

Arrival of Catholic missionaries who introduce Christianity.

1910s

Belgium occupies Rwanda during World War One.

1922-24

The kingdoms of Rwanda and Burundi are merged into a single colonial territory known as Ruanda-Urundi. Belgium is granted League of Nations mandate to govern the region, which it rules indirectly through Tutsi kings.

1933

Belgium introduces mandatory ethnic identity cards distinguishing Tutsi, Hutu and Twa.

1959

After decades of colonial oppression, the Hutu majority rebels against Belgian powers and the Tutsi monarchy, leading to thousands of Tutsi deaths and mass exile to neighbouring countries.

1961-62

Rwanda gains independence from Belgium. The Tutsi monarchy is abolished and a Hutu president is installed amid growing ethnic conflict.

1980s

480,000 Rwandans become refugees.

1987

The Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel group formed of Tutsi exiles, is founded in Kampala, Uganda.

1990

The Rwandan Armed Forced (FAR) begin to train and arm civilian militias known as Interahamwe (‘Those who stand together’).

October 1990

The RPF army launches a major attack on Rwanda.

August 1993

Peacemaking efforts appear to bring an end to the conflict between the RPF and Hutu government.

6 April, 1994

The plane carrying the Rwandan and Burundian presidents, both Hutu, was shot down with missiles above Kigali, Rwanda. Both were killed.

7 April, 1994

Start of genocide

July 1994

Over 100 days, 800,000 to 1,000,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed by the FAR and Interahamwe. An estimated 100,000 to 250,000 women were raped.

April-July 1994

The RPF, led by Paul Kagame, takes control of Kigali, ending the genocide.

1996

The start of national genocide trials. Trials and efforts to track key genocide suspects continue today.

2001

A new flag and national anthem, which refers to the Rwandans as one people, are announced.

2003

Paul Kagame wins the presidential election. The RPF later wins an absolute majority in the parliamentary elections, amid accusations of fraud.

2004-Present

The government implements land reforms, including land consolidation programmes and titling initiatives, to resolve disputes and to improve land management, decrease degradation and increase agricultural productivity.

2013

Israel signed secret agreements with Rwanda, implementing a ‘Voluntary Departure’ scheme for asylum seekers. Plans to forcibly deport asylum seekers were scrapped in 2018, following international criticism.

2017

President Kagame is re-elected for a third term with 98.8% of the vote after winning a referendum on constitutional changes that allows him to stand again. Critics say that opposition have been threatened or arrested and independent media silenced.

2023

The UK paid £240m to Rwanda ahead of plans to forcibly deport people seeking asylum in the UK.

7 April 2024

30th anniversary of the genocide.

15 July 2024

Presidential elections. Kagame secures a fourth term with what is declared as more than 99% of votes cast