Edited extract from Where Light in Darkness Lies by Veronica della Dora

Lighthouses are special places. Quietly suspended between the sea surface and the sky, solidly implanted on the edges of the land, insistently battered by the waves and the wind, lighthouses physically mark the encounter between the elements. They guard the boundaries between the world of humans and the primordial chaos of the water; between perceived stability and instability; between the known and the unknown. As such, they seem to hold a strange universal appeal that few other man-made structures are able to boast.

Functional structures largely standardised around the world, lighthouses are nonetheless treasured as distinctive local and national landmarks. Indeed, some have long been famous urban icons – think of the Lanterna of Genoa, for centuries watching over the city and its port from the height of its slim, austere pillar, or of the stone lighthouse of Alexandroupoli in northern Greece, standing on the waterfront among crowded apartment blocks and buzzing cafés like a cheerful old friend.

In antiquity and throughout the Middle Ages, lighthouses fulfilled their duty by way of simple systems, such as fires in braziers set atop towers or on movable winches. But over the centuries, they’ve become increasingly sophisticated and their light increasingly powerful and reliable. New combustion materials have played their part, evolving from wood and coal to vegetable and animal oils, and, finally, during the late 19th century, to gas and electricity.

The introduction of new optical technologies such as parabolic reflectors and special lenses enabled the maximisation of the range and intensity of the light by channelling it in one direction. Notably, in 1822, the French physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel developed a composite lens that was able to capture more oblique light from a light source, thus allowing the beam from a lighthouse to be visible over greater distances. Intermittency was produced by the revolution of the lantern thanks to a rotating system pioneered by the Swedish mathematician and engineer Jonas Norberg about

40 years earlier.

Before the invention of rotating systems during the late 18th century, all coastal lighthouses showed fixed lights, and mistakes of identification often resulted in wrecks. Today, most lighthouses rhythmically flash or eclipse their lights to signal the entrance to a port, the edge of a cape, or a perilous reef or shoal. At the same time, their flashing patterns also provide an identification signal. Each lighthouse and major buoy has its own luminous signature, whether the type of flash, the colour of the light, the duration of exhibition or a combination of these.

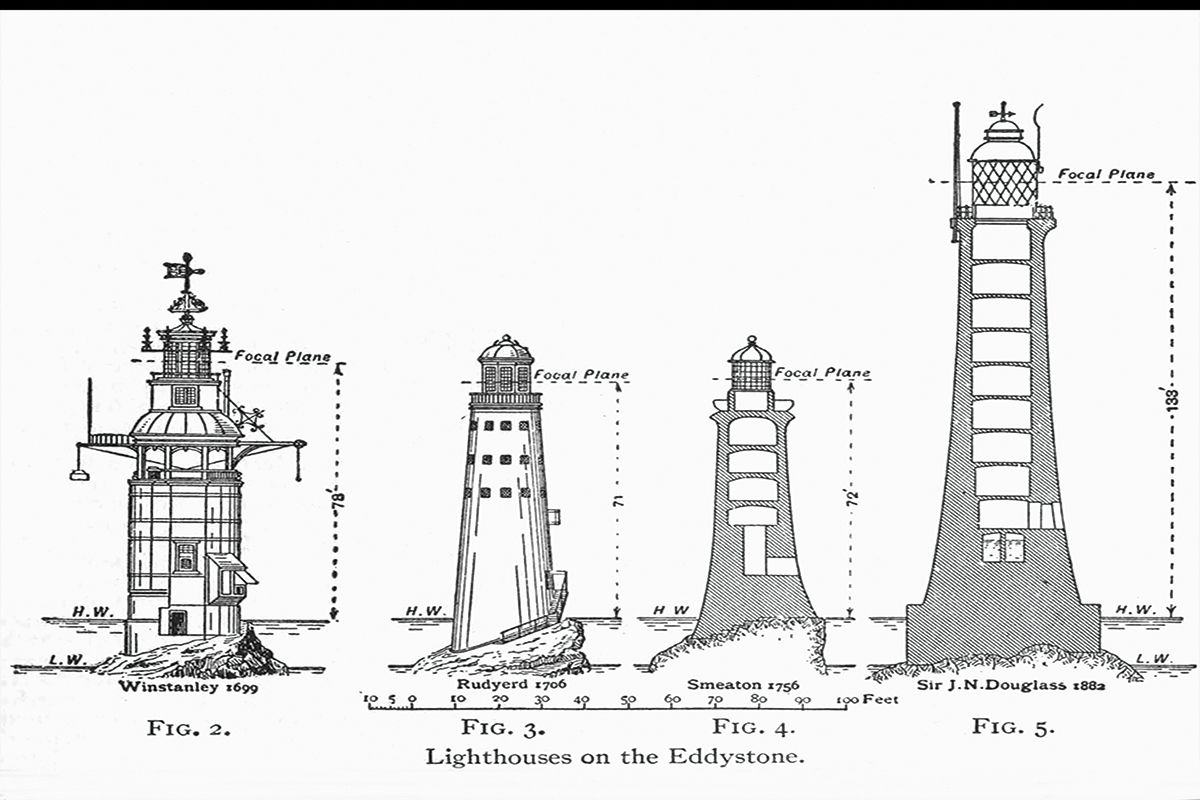

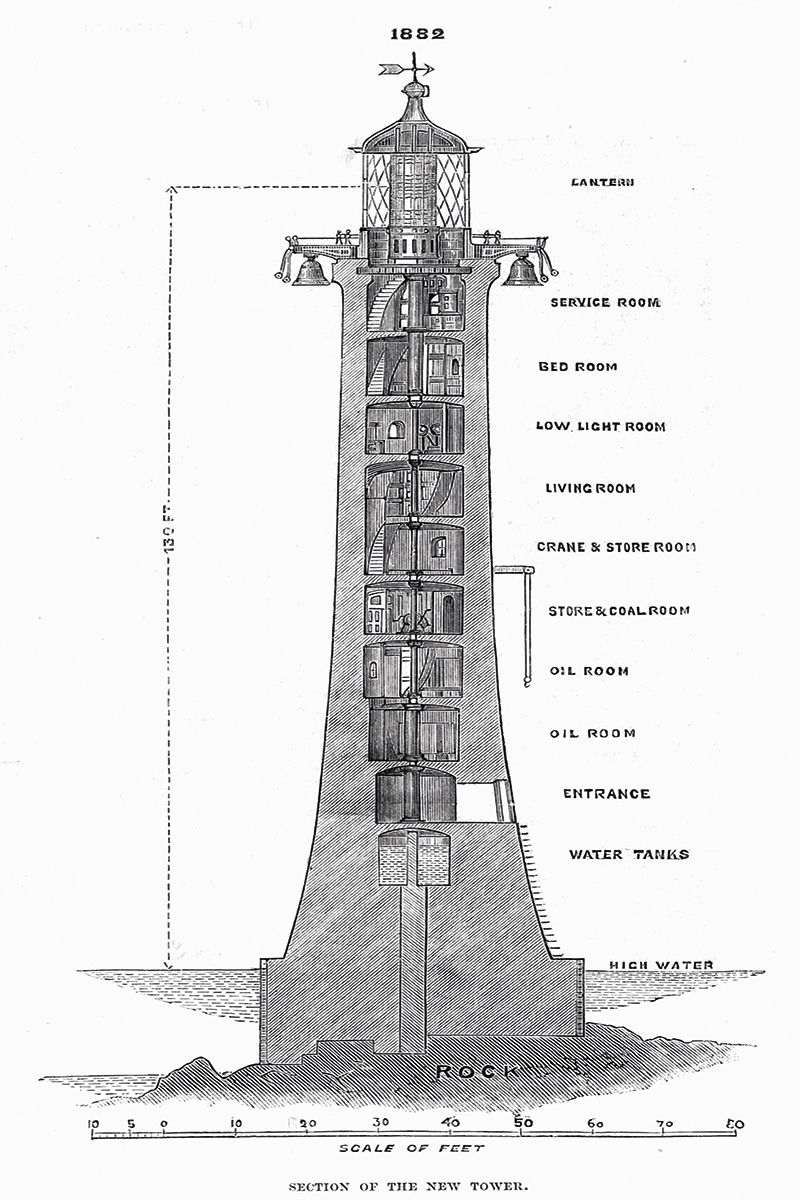

While lighthouses are, by definition, bearers of light in the darkness, they nonetheless also fulfil their function as beacons in full daylight through their very structure. Their characteristic conical hyperbolic profile, pioneered by John Smeaton during the 18th century and popularised by the Stevenson family the following century, is employed to minimise resistance to the elements. It lets the wind and waves flow easily over it, ‘deflecting rather than opposing the violence that would be unleashed by resisting the momentum of massive storm waves’.

Icons of pure functionalism, with their delicate proportions and clear lines, these isolated wave-washed structures possess a strange and remote beauty. The sinister and forbidding sound of their names comes from the treacherous hazards they mark: Eddystone, Skerryvore, Dhu-Heartach (Dubh Artach), Wolf Rock, Minot’s Ledge, the Graves and many others.

While rowdy, rock-strewn cliffs and hidden reefs presented an obvious hazard to sailors, the soft sandbanks of shallow seas and estuaries were an equally sinister threat. Of the Goodwin Sands Downs, for example, the English antiquarian and lighthouse historian William Hardy wrote: ‘No more treacherous shoal exists than that ever-shifting mass, that greedy monster that lies beneath the surface of the water, and grasps in the clasp of death every luckless vessel driven within its reach.’ So, from the 17th century onwards, light vessels were employed on bed estuaries and muddy shoals, where erecting a lighthouse was impossible, especially in the northern seas. Lightboats were anchored on the spot and signalled the hazard. Crews stood for weeks at the mercy of the elements, their vessels uncomfortably pitching and rolling in short, heavy seas, ‘the distant shore forever distant’.

During the 20th century, new building technologies enabled permanent lighthouses to be implanted on these treacherous spots by way of prefabricated telescopic concrete structures sunk onto prepared gravel beds. In 1971, the Royal Sovereign lighthouse, located 11 kilometres offshore from Eastbourne, replaced a lightship that had marked the eponymous shoal since 1875. Its distinctive unbalanced structure, comprising a large platform supported by a single concrete pillar, was built in two sections on the beach of Newhaven.

Situated on windy capes, the edges of piers or the tops of stormy cliffs and rocks, lighthouses are structures set between the untameable forces of nature and the ordered world of humans. Lighthouses are also precarious markers of the consequences of the Anthropocene, the recently recognised geological era in which humans have taken a leading role in shaping the planet. They serve as barometers and icons of some of the most extreme consequences of climate change, including rising sea levels and coastal erosion, as well as increasingly violent storms and severe winters.

Sometimes, from impassive witnesses and immobile markers, lighthouses can become victims of the drama – and objects of spectacular rescues. When the 23-metre Rubjerg Knude lighthouse was first lit in 1900 in northern Jutland, Denmark, it was roughly 200 metres away from the coast. Over the years, that distance shrank to six metres and the lighthouse was predicted to fall into the sea by 2023, together with the cliff on which it stood. In 2019, however, the Danish government spent five million kroner (£580,000) on specially built rails to wheel the structure 70 metres inland from the cliff edge. The event received vast media coverage in Denmark and abroad. Although the lighthouse had ceased to operate in 1968, when sands slowly buried two adjacent buildings, it was deemed a national treasure worth saving.

On the other side of the Atlantic, similar public attention was generated by the 60-metre Cape Hatteras lighthouse when, in 1999, it was relocated 884 metres inland to save it from the encroaching sea. On the eastern coast of England, where, exacerbated by climate change, erosion is likewise at work more dramatically than ever, less-fortunate lighthouses risk a darker fate or, at least, permanent separation from the mainland.

Lighthouses, however, aren’t passive barometers of environmental change. Their material presence in the landscape and their decay do bear an ecological cost. Their light has long had a devastating impact on certain animal populations. Since at least the 19th century,

for example, it has often been reported how, attracted by the light, entire flocks of seabirds dash themselves against the glass of the lantern, meeting a violent death. Notoriously, the Statue of Liberty’s lamp killed tens of thousands of birds, with more than 1,300 dying in a single night in October 1887.

For their part, old nuclear-powered lighthouses pose a threat to entire regions of the planet. By 1994, there was a string of 132 of them guarding the Soviet Arctic coastline, from the Kola Peninsula to eastern Siberia. Built during the 1960s and ’70s, these structures had generators that ran on strontium-90, one of the deadliest nuclear fuels. Over the past few years, their unguarded or abandoned structures have been vandalised and two generators have gone missing, while radioactive waste has sullied Arctic rivers flowing into the Barents and Kara seas.

And yet, these ‘dark’ lighthouses stand as almost an oxymoron. For, ultimately, in the collective imagination, lighthouses are the epitome of strength – bearers of hope, unmistakable symbols of ‘man’s best intentions and deeds’.

A broken lighthouse stands for a defeated humanity. A hazardous lighthouse is a likewise disturbing and incongruous image, much more so than, say, a hazardous power plant or factory. The reason perhaps lies in the emotional charge with which we invest these structures. We attribute to them anthropomorphic traits (such as a ‘surveying eye’ or a ‘body’) and even human agency: lighthouses ‘guide’, ‘direct’, ‘save’. We call them ‘sentinels’, ‘guides’, ‘companions’. We’re mysteriously attracted to them.