The route of Julian Sayarer’s 4,000-kilometre bike journey. llustration: Bill Donohoe

Julian Sayarer has travelled across and reported on vast swathes of the world by bike. For his latest epic journey he tackles a country close to his heart – Türkiye, the land of his father and his second home

On a late autumn day last year, outside a grand house on a backstreet of the Greek port city of Thessaloniki, I took a photo of my touring bicycle loaded with panniers. The house was the childhood home of Mustafa Kemal, better known as Atatürk – the man who, more than any other, is credited with founding the Turkish Republic, but who was born in what is now Greece. It’s an indication of the diverse and disparate nature of the Ottoman Empire, which, before its collapse, was a borderless territory that spanned from what used to be Yugoslavia to Yemen.

As I framed my bicycle for the photo, a young man with a thin beard walked towards me and we greeted each other in Turkish, then English and then a mixture of the two. He offered to take a photo of me with my bicycle and said that he too had made the journey I was about to, setting out from the eastern Turkish city of Diyarbakır and riding across the country, east into Georgia, before back west to Greece. There he had fallen in love and married his wife, and Thessaloniki was now home. I remarked that I was riding towards Diyarbakır myself and asked if he was Kurdish. He rolled his eyes and replied: ‘Turkish, Kurdish, Greek. To me it is the same thing.’

A Significant Year

I’m half Turkish, half British and despite having previously cycled a number of times between the UK and Istanbul, I was self-consciously aware that I had never cycled much further east in Türkiye than the west coast, near my father’s home city of Izmir.

My bike journeys over the years had taken me across China, the Americas, Palestine and Central Asia, but had yet to include a country that – despite not growing up there – had become as much a home to me as the UK.

It seemed the right time to address this, as the following year marked an important date in Turkish history. The Ottoman Empire came to an end in 1923, so this year consequently marks the centenary of the foundation of the Turkish Republic.

If 2023 was a significant year for Türkiye, it was no less so globally. Supply chain shocks brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic induced rampant worldwide inflation, to which Türkiye is particularly vulnerable. Central banks hiked interest rates in a desperate effort to bring inflation under control. The Russian invasion of Ukraine was in its second year.

When I set off in the autumn of 2022, the climate of war and Western sanctions on Russian gas had turbocharged inflation with an energy crisis, and as I cycled east from Greece towards Istanbul, that feeling of simplicity and peace that’s so inherent to cycle touring seemed at odds with a precariously balanced world.

Cycling past the fields and mountain lakes of the Balkans, where shepherds speak both Turkish and Greek, it was sobering to consider that Russian expansion during the late 19th century, together with the British, had helped Greeks and Bulgars empty the Balkans of their Turkic and Muslim populations. A century later and Türkiye, now a NATO member but fearful of further escalation across the Black Sea, was helping mediate Russian–Ukrainian prisoner exchanges and guarantee the so-called ‘grain corridor’ that tried to keep Ukrainian harvests supplying world markets. A few weeks later, a baker I drank tea with in the city of Adana would lament the rising cost of flour, one of many moments in which the roadside would intersect with the political machinations that churn high above the lives of regular people.

The first major waypoint on the journey through Türkiye was, of course, Istanbul, a city that always feels as if it’s moving fast enough to keep up with a changing world. When I first lived in Istanbul in 2007, teaching English for a year, the metro consisted of barely ten stations. Now, it comprises a dozen lines that connect a city and three airports, one of which is the world’s largest. New stations under construction are still having their tunnels bored, joining train lines to ferry terminals and on to the satellite cities across the Sea of Marmara. The Istanbul municipality slogan, ‘We’re working for 16 million’, attests to a determination to create amenities that match its size.

Sipping coffee in a park during a brief rest from cycling one morning, I heard a nanny speaking Turkish to a baby who, by its name, was either Russian or Ukrainian – evidence of a new refugee population that the city is absorbing. This is a city that always seems to be at the centre of things. As Napoleon said: ‘If all the world were a single country, then Istanbul would be its capital.’

However, for all the allure of Istanbul, I knew that I had no time to dawdle. Already November was upon me. I’m familiar with both cycling in mountains and the topographical map of Türkiye, but it’s only in the saddle that the hills and peaks of Anatolia impress upon you their full, endurance-sapping relentlessness. On reaching the higher altitudes of the interior plateau, you’re kept comfortable in terms of oxygen but not weather. As I rode, the days shortened with the coming winter, temperatures dropped and I faced the familiar touring-cycling dilemma of sweating and then shivering as ascents turned to descents. Now and then, in the remotest mountains, I was pursued by wild dogs. Other times, the chase was from the shepherd dogs that keep the wild dogs and wolves away from their flocks.

At such times it’s easy to start questioning if this 4,000-kilometre bicycle journey, whatever discovery it yields, is truly worth it. The answer, as with all adventure that at the time can feel absurdly difficult, is always ‘yes’, but sometimes it was only in the evening behind the closed door of a pension or the wall of the mosque gardens in which I often bivvy, that I felt sure of this.

One of the greatest advantages of travel by bicycle is its immediacy. As I rode, I considered how Türkiye, and still more those countries to the south and east, are often seen in terms of their past. Books talk of Romans, ancient Greeks, Ottomans, or go further back to Hittites, Assyrians and even more ancient people. There’s a fascination and fetish for the history in those countries the West calls the Middle East, an exoticised category in which Türkiye – fortunately – is only sometimes included. Sometimes this respect for cultural heritage can be welcome, but I wondered what is missed by always looking back, and why the Western gaze is so focused on imperial pasts.

This fixation on history is ironic, too, because nothing in Türkiye feels so unmistakably present as the future. The world’s longest suspension bridge, with a span of 5.3 kilometres, joins the Anatolian city of Çanakkale to the Gallipoli Peninsula and Thrace. The bridge surpasses the length of the world’s previous longest in Japan to provide the first non-Istanbul crossing of the Turkish Straits. A central section of 2,023 metres marks the year of the centenary and shortens by hours a journey that hauls goods from the manufacturing heartlands of Türkiye towards the European markets.

At the roadside, solar farms climbed across the contours of the land in a shimmering blue haze, the fields offering a harvest of both olives and the sun’s energy. Wind turbines are commonplace, supplying power for local factories and the national grid, and Türkiye is even selling them to European countries.

If this inspired hope, I also crossed a forested region known as the Kazdağları, where, unfortunately, gold lies close to the surface of the soil, and a Canadian company, Alamos, is suing the Turkish state for heeding local protests and revoking its permit to clear-fell trees and mine the land in this pristine region. The lawsuit is a reminder that Western corporations are often happy to see democratic voices sidelined when it suits their profits.

Moving inland, columns of steam lifted from large chimneys. In a region rich with thermal spas, geothermal plants have sprung up, making the country one of the world’s largest producers of this crucial green energy, which keeps producing even when the sun and wind don’t.

Frequently, I marvelled at the progress I saw compared to the country I spent holidays in as a child, but this economic growth has consequences. While the heat that powers geothermal plants is abundant, the water needed is increasingly scarce. I spoke to a craft brewer in the Menteşe mountains, asking if he used Turkish barley for his brewing, to which he shook his head, replying that his is imported from Germany, and agricultural corporations have withdrawn from Türkiye citing the long-term probability of acute water stress. ‘Maybe in 30 years we are lucky and we start to have a lot of rain,’ he says. ‘But I’m not sure.’

Further east, the politics of water only grows. All across the country are hydropower facilities that generate energy for the Turkish grid, but it’s in middle Anatolia that great dams rise in the hills. Low rainfall already depletes power output from this inherently climate-vulnerable form of green power, yet problems are amplified all the more for Türkiye’s southern neighbours.

Upstream dams slow the tributaries that feed the mighty Euphrates and Tigris. Turkish hydropower now leaves Syria and Iraq with only a limited flow of river water. Turkish agriculture often utilises modern, water-conserving irrigation methods, but the ongoing dysfunction that has plagued both Syria and Iraq since the US invasion makes it difficult to establish fair regional use of this vital resource. Without stable governments, it’s impossible to negotiate river rights. Some lateral thinkers have proposed an Iraq–Türkiye swap deal of (abundant) Iraqi gas for (scarce) Tigris river flow, allowing Türkiye to use gas to replace some of the hydropower that now generates a quarter of its electricity. But such a deal only locks in the hydrocarbon dependency that is the root cause of our shared crisis: climate change.

If water moving south has become a prominent cause of discord, the mass relocations of humans moving north, particularly Syrians fleeing civil war and US sanctions, has similarly marked politics in southern Türkiye. Although regions such as Gaziantep historically have a mixed Turkish-Arab heritage that helped it welcome one of the world’s largest refugee populations – officially reckoned to be 3.5 million and unofficially somewhat more – the political strain still shows.

Near Mersin, I pedalled beside an EU–Türkiye-funded ‘crisis centre’ being built for migrants. Soon after my journey, an election is contested in which xenophobic campaigning is rife, particularly from the more pro-West Republican People’s Party. I spoke to a woman, a voter for Erdoğan’s AKP, but who questioned the idea that her being a Muslim obliges her and Türkiye to welcome all the refugees of Syria and, increasingly, Afghanistan, where US sanctions have helped to usher in a famine. She expressed resentment that Europe never helped, as it pledged, to resettle refugees from inside Türkiye. I recalled that in 2016, as Türkiye took in four million Syrian refugees, the UK accepted just 10,000. It’s hard not to feel that she has a point.

Mismanaging Geography

My ride finished on 1 December 2022 in the eastern city of Kars, on the Armenian border, where I stowed my bicycle aboard a sleeper train heading towards Ankara. In the early hours of 6 February, an earthquake of 7.8 magnitude struck, followed by a second at 7.5, along the East Anatolian Fault, which I had just ridden above. Adana-Osmaniye-Gaziantep-Diyarbakır was my route, and so too was the path the earthquake took. The news reports shows flattened cities where I so recently recalled looking out from a hotel window. At least 50,000 people died, with some 6,000 more in Syria. Turkish society did what it could, donating money, spare rooms, spare clothes, battery packs and anything of help. Large hotels on the Aegean coast, closed for the tourist off-season, opened their rooms, but even this is only a small, well-meaning dent against millions of lost homes and livelihoods.

The fingerprints of geography and how we manage it mark the disaster. Houses built on shifting, shallow foundations crumble in the earthquakes – a stark metaphor for the risk of leaving unmanaged the rural-to-urban migration that’s a hallmark of globalisation, and certainly the last half century in Türkiye. The rush of money from migrants buying homes, especially in Syrian-border provinces such as Antakya and Hatay, saw a property boom in which building regulations were lax, leaving unsafe homes that the government nevertheless signed off as compliant during a 2018 construction amnesty, while pocketing the tax revenue.

Looking back at a journey, it’s never easy to draw simple conclusions. The random nature of moving through a landscape always disproves more conclusions than it offers; one idea is refuted by another further down the road. It’s this collision with the real world that provides an unrivalled understanding.

Using a journey to take a reading of a modern, rapidly evolving country is implicitly political. States are, after all, the way in which humans manage, or often mismanage, geography. I’ve come to think that we aren’t prisoners of geography, as is so often stated. Countries might be an imperfect unit for organising ourselves, but they’re a recognition that to do so is possible. For a century that began with victory over European colonial powers and now ends with a global economic crisis, things are certainly not plain sailing in Türkiye, but the bicycle has a good way of reminding you that in life, just as in history, things keep moving forwards.

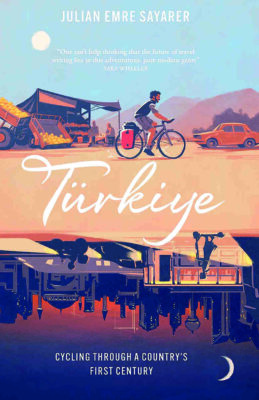

Türkiye: Cycling Through a Country’s First Century published by Arcadia Books