Gorgona Scalo, Italy’s only prison island, is a radical experiment in penal reform, providing humanity and a sense of freedom for the incarcerated

Words by Federica Tourn • Photographs by Federico Tisa

Weather permitting, the ferry from the Tuscan port of Livorno arrives twice a week on the tiny rock outcrop of Gorgona. A few curious tourists make the hour-long trip, along with essential supplies for one of the last prison islands still operating in Europe.

Convicts have been incarcerated on this two-square-kilometre lump of rock isolated at the far north of the Tyrrhenian Sea since 1869. Today, it houses up to 80 male inmates in what is a radical experiment in rehabilitation for the overcrowded and under-resourced Italian penal system.

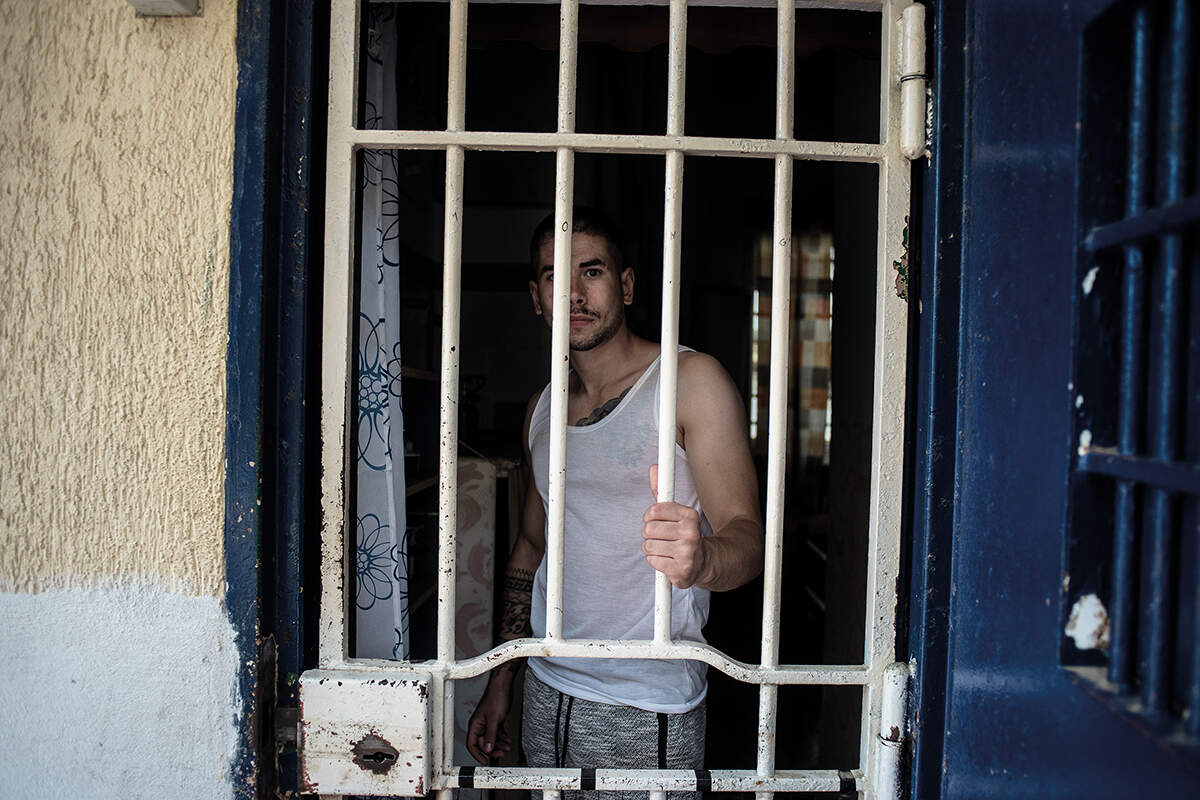

This is an open prison. The men are only held in their cells from eight in the evening until six the next day. In the morning, the iron doors of the cell blocks are unlocked and the inmates are free to go out into the orchards, to work among the vines that cover the hillside, or to look after the animals. Some work in the kitchen; others clean or maintain the institution’s crumbling buildings. In the afternoon, they can do volunteer work, play sport or participate in cultural activities. They can meet with the public and even have lunch with their families.

All of the prisoners – who tend to be offenders reaching the end of long sentences for serious crimes – are paid for their labour. Some of their wages go towards their upkeep, some go to help support their families and a part is kept for their release.

Fifteen of the inmates are employed by the famous Frescobaldi wine-making dynasty. They produce an award-winning white wine on the island sold as Gorgona for €90 a bottle; only 4,000 bottles a year are produced. The inmates, who don’t get to drink any of their produce, are paid the same as other workers employed by the 700-year-old company on its six mainland estates.

Surrounding the vineyard are vegetable gardens in which tomatoes, aubergines, courgettes and basil grow. Cheese, bread and honey are also produced on the island.

This unique experiment was started 30 years ago by Carol Mazzerbo, an ambitious young prison officer fed up with working in a high-security penitentiary that held senior mafia and terrorist convicts.

‘When I heard there was an opportunity to go to Gorgona, I jumped at it,’ Mazzerbo remembers. ‘I was the only candidate; they were not able to find anyone else who wanted to go.

‘I thought I would stay two or three years, and then I fell in love with the place,’ he continues. ‘It was an opportunity to provide a different kind of prison system that was more human, where people can look each other in the eye.’

It became a life-long project and he has struggled to keep it open, enlisting support from such as the Frescobaldi family and leading lights in the Italian arts. He retired as director last year, and despite the prison having a recidivism rate of 20 per cent – compared to 80 per cent in other Italian jails – he fears for its future.

To raise the island’s profile, Mazzerbo persuaded the leading director Gianfranco Pedullà to bring his Teatro Popolare d’Arte company to the island to work with the prisoners. In the summer, the inmates staged an open-air performance of Ovid’s Metamorphosis.

‘There’s the risk that the prison here will be closed,’ says the former director. ‘That is why I have worked a lot on public relations, on the involvement of companies and the municipal administration, which have, so far, all committed to keeping the prison open.’

I come across a group of prisoners chatting and leaning against a wall, their cigarettes held in the palm of their hands to protect them from the wind. ‘Here, no-one has ever asked me what I’ve done’, says Vito, who had been held in a tough prison near Naples for 14 years. ‘There is humanity here; when you have problems, you are listened to and the guards try to help you out.’

Riots were commonplace in his previous prison and 105 officers were brought to trial for beating inmates in 2020.

Later, in the kitchen area, Luigi, another former inmate from the same mainland prison, tells me: ‘There we were just numbers. I saw many fellow inmates kill themselves to escape the continual mistreatment.’ Other prisoners I chat to all have bitter memories of their previous prisons. All have benefitted from the regime in Gorgona. One has taken to writing about his life and has just had his first novel published. Another who was jailed for murdering his business partner tells me he’s about to go home. When his wife first visited him, she couldn’t look him in the eye. Now they are going to renew their vows on his release.

One of the prison officers, Pierangelo Campolatano, who has spent the bulk of his career on the island, tells me: ‘We live in a sort of community where everyone has their own role. It is a model with a lot of potential that should be copied.’