Bryony Cottam visits Bellerby & Co, one of only a handful of firms making handcrafted globes

Globes cover every available surface of the Bellerby & Co Globemakers studio in Stoke Newington, northeast London. Clustered on the windowsills and cabinet tops that surround each area of the warehouse’s upper floors, in which a team of globemakers are methodically working away, they range from football-sized (22 centimetres diameter) to giant spheres in various shades of blue, grey or aged-looking browns. ‘They’re all defective,’ says Peter Bellerby, gesturing to the many painstakingly crafted globes on display against the walls. ‘They’re not for sale.’ When asked why, he pauses, then says, ‘They’re just not up to our standards.’

Bellerby & Co Globemakers is one of the last few producers of handcrafted globes. Only a handful of others can be found across Europe (including Greaves & Thomas and Lander & May, both on the Isle of Wight) and in the USA. But centuries after they first became popular, handmade globes are making a comeback.

Like most of the people producing globes today, Bellerby doesn’t come from a long line of globemakers (the 58-year-old previously worked in TV licensing, travelling all over the world selling British documentaries to foreign markets). He set the company up in 2008 after being unable to find a suitably ‘beautiful’ globe as a present for his 80-year-old father, a naval architect.

As the globemaking profession declined, many of the skills needed to craft a globe were lost along the way. They’ve since been revived and, in some cases, revised, a challenging process that has caused no end of problems for would-be crafters. ‘There is no manual and nowhere to learn to make globes,’ says Bellerby, who spent two years trying, through trial and error, to make his first, almost bankrupting himself in the process.

‘Globemakers were not particularly forthcoming about their methods of construction,’ Sylvia Sumira writes in The Art and History of Globes. Sumira is a globe conservator, one of few who specialise in printed globes, which first began to appear during the mid-1500s. ‘Sylvia knows everything there is to know about how globes are made and how they have changed over time,’ says Joshua Nall, curator of the globe exhibition at the Whipple Museum of the History of Science in Cambridge. In her book, which Nall describes as the go-to source for a history of globemaking, Sumira reveals some of the secrets of the craftsmen who produced the globes still preserved in museums and private collections.

A small number of written accounts, which have been verified during restoration work, show that old globes typically started life as two papier-mâché hemispheres, formed using strips of paper (rather than pulped paper) that were applied to a wooden or copper mould. All sorts of paper was used, including pages torn from books, even manuscripts and maps. Once the two halves of the globe were joined together with more paper and paste, the whole thing would be covered in a level layer of plaster, similar to the way a baker would ice a cake. If the coverage was uneven, as was often the case, then the globe would be imbalanced and would always fall back to the same position. To demonstrate, Bellerby gently spins a 1930s Philips globe – one of a few antique globes he keeps in his office. It soon starts to swing like a pendulum. The cloth filled with lead shot, commonly glued to the inside of a globe to re-balance it, has slipped, he explains.

Bellerby doesn’t make his globes from paper and plaster. ‘We used to, but – have you worked with plaster of Paris? It was a mess, the dust gets everywhere.’ Meanwhile, he found that larger plaster-made globes (50 centimetres and above) simply fell apart under their own weight. These days, Bellerby & Co Globemakers outsources all of its spheres, which are made from GRP – glass-reinforced plastic, also known as fibreglass – or resin. ‘No-one else knows exactly where our spheres are made,’ says Bellerby, keeping his cards close to his chest. After some questioning, he lets slip that they all come from a small warehouse, somewhere on the southeast coast. ‘The man who makes them for us must be in his 70s now,’ he muses, ‘but he’s our only supplier.’

While its core material has changed, the company’s globes are made in much the same way as a 17th-century one, requiring a team of five ‘makers’, eight painters and an illustrator. It takes a lot of hard work and dedication to become a globemaker. A recent advert for an apprenticeship in January this year stated that applicants should show patience, perseverance and be receptive to constructive criticism. A perfectionist with excellent fine-motor skills, ideally with a background in miniature model-making, sculpture or watercolours, might suit the role. ‘It takes at least a year of training to be able to make just the smallest globe,’ says Bellerby, ‘and it’s full-on, every day. There’s no tea making here.’ Each apprentice hired is a two-year, £150,000 investment. Even so, there have been times when it hasn’t worked out. ‘We’ve had new apprentices that do really well on their trial day, but then struggle with the work later on down the line.’

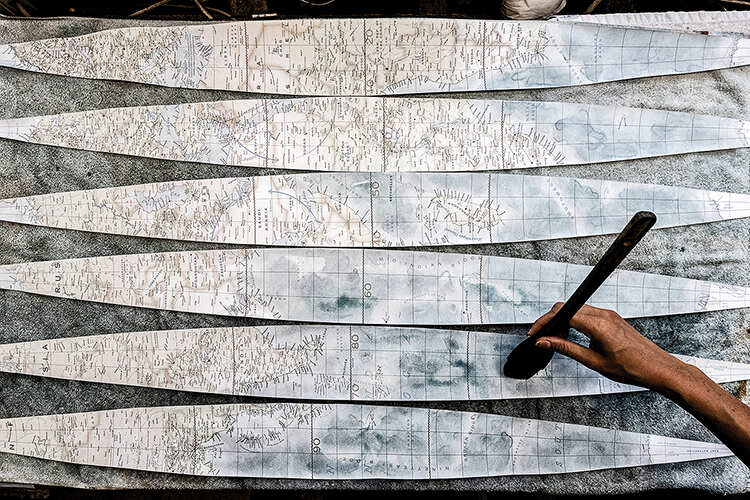

There’s no room for errors when making a globe. In other forms of art, Bellerby explains, mistakes can be corrected and it doesn’t make the finished piece any less valuable. But globemakers work with gores, which pose a unique set of challenges. These long, thin, oval-shaped pieces of pre-printed paper must be carefully cut by hand and painted with a translucent wash of watercolour that lets the coastlines and place names show through. It’s a process that can take five to ten days, says Isis Linguanotto, head painter and a globemaker for ten years, who sits at a wooden workbench cluttered with jam jars of ink-coloured water, brushes and well-used paint palettes. A row of half-painted gores has been laid out flat to dry. Linguanotto will build up the thin layers of paint to shade and define borders and landforms – details as important for readability as aesthetics.

Once the painters have finished the first stage of their work, each gore is dipped in water, making it pliable (and very fragile) so that it can be stretched and carefully pasted to the fibreglass sphere. Most globes use 12 gores – larger ones may need 18 – and each must align perfectly with its neighbour, without overlapping, to ensure that every map line meets in the right spot. Overwork the paper and it will deteriorate and tear.

Over time, with the development of colour lithography and modern printers, globemaking has become cheaper, and its methods have been simplified. A 1930s British Pathé film shows a production line of hand-gored globes as they are swiftly pasted and sealed. ‘But then you lose half the detail,’ says Bellerby, who is fastidious about quality. He confides that finding the right candidates to be apprentices has proved challenging. New globemakers are asked for a minimum five-year commitment and join an ever-expanding team (including six warehouse workers, who build each base, and an engraver) that currently produces between 40 and 45 globes a month.

From the studio, Bellerby’s globes go all over the world. Orders are regularly sent out to Europe, Asia, Australia, Brazil and Canada. Jade Fenster, who manages much of the day-to-day running of the company, estimates that there’s a Bellerby globe in every US state. ‘We’ve sent a few to Africa and beyond, too. We had one globe go to Papeete, in French Polynesia, and another to Greenland.’ They’re sold almost exclusively online (Harrods stocks a handful of the smallest ‘desk’ globes), where prices range from roughly £1,500 to £79,000 – that’s before any customisation. ‘All of our globes are bespoke,’ says Fenster, ‘Customers always work with us one-on-one to design the globe exactly as they would like it, from the size to the colouring, base material, base finish, base design and engraving, as well as the map design. The pricing is to book in and the extra work is quoted on top,’ she adds.

Alongside the many globes deemed to be substandard, the studio is currently home to several completed globes and various works-in-progress. Half a dozen people are working on their part of a project; in one corner, painters are painting, in another, makers are goring. The workshop below, filled with wood and tools and half-built bases, is currently unoccupied and the studio is hushed and peaceful. Gores hang drying like washing on a line. Bellerby walks to the end of the warehouse, where, looming between the busy workstations and backlit by a flood of natural light coming from the floor-to-ceiling windows, a gigantic sphere is concealed by a purple cloth. He unveils it, magician-like. At 127 centimetres (it’s even taller atop its base) the ‘Churchill’ is the largest globe produced by Bellerby & Co. Globemakers. This one is destined for China; three more in the warehouse will be shipped to the USA, another to Dubai.

Despite their impressive size, they’re not the most unusual globes made in the studio. The company offers fully bespoke globes and receives many requests for custom personalisations. Some are beautifully illustrated, intimate narratives of family histories and migrations or holiday memories. Others have been made for touring bands, films and organisations, or plot historic travel routes. One globe, produced for a collector who supplied an entire spreadsheet of data, maps the major straits, shipping routes, undersea cables and various city demographics.

Historically, globes would have been extremely valuable, rare items. Many have often survived only through the collections of extremely wealthy and influential people. Before printed globes, all globes were manuscript globes – hand drawn, painted or engraved directly onto a sphere – and made in small numbers. Very few of the earliest globes have survived at all. The oldest is the Farnese Atlas, a second-century marble globe held on the shoulders of a Greek god (now in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples). Islamic celestial globes made as early as the 11th century can still be found in museums and private collections, while the oldest surviving terrestrial globe is the Erdapfel (German for ‘earth apple’), dating to 1490. It was only in the 19th century – a period of incredible growth in the consumer market for what Nall calls ‘science at home’ – that makers began to produce them at a price affordable by the middle classes. They remain a prestigious item to own, but globes have always represented much more than this. Nall points to the Whipple Museum’s globes, which take ‘many, many different forms, some of them quite weird and unexpected. Our collection is indicative of the fact that, particularly in the past, globes served lots of other purposes beyond merely being a representation of the political division of countries on Earth.’

According to Sumira, as globemaking evolved, ‘map-makers became concerned with new ways of representing the constantly changing view of the Earth and heavens’. Among its many geological globes, the Whipple Museum counts a Russian-made example that presents a rival theory to plate tectonics (‘the Soviets didn’t really want to accept plate tectonics because it was a Western scientific theory’) and a succession of Mars globes, each an attempt by a particular astronomer to establish his or her own representation of the planet. ‘These started being produced from the middle of the 19th century, at a time when telescopes were just becoming powerful enough to draw a plausible map of the planet,’ says Nall. ‘Almost immediately, the main players got globes made from their maps.’

One of these globes, hand-painted by Danish artist Ingeborg Brun, depicts Percival Lowell’s theory that the long channels seen on Mars (now known to be an optical illusion) were built by Martians as irrigation systems. Brun’s globes have made their way into the Vatican, the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, the Lowell Observatory in Arizona and, of course, the Whipple Museum. ‘She sent them all over the place as a means of promoting Lowell’s ideas.’ For anyone who had an idea, argument or theory, a globe was a particularly powerful way of embodying it. Sumira writes that globes encapsulate ‘the need to find our place in the cosmos.’ It could explain their enduring popularity.

No matter how unusual the design, all of Bellerby & Co Globemakers’ globes are meticulously mapped, often down to minute details. It’s a full-time job for two cartographers; a third works part-time. The world and its features are constantly morphing as rivers change course, ice shelves calve and eruptions create new volcanic islands. It’s surprising how many cities have emerged, borders have shifted, capitals have moved and new countries have formed in just the last ten years. One of the company’s cartographers spent a whole year fully updating every one of the maps used. ‘There’s no one database with all this information available,’ says Bellerby. ‘We simply have to stay on top of the news.’

For now, globemaking remains an endangered craft – it features on the Heritage Craft Association’s ‘Red List’. However, these days its future looks a little more certain. It’s slowly attracting new, skilled artists and interest in products from both the London studio and beyond.