England has long suffered from a North–South divide. Despite numerous attempts to tackle it, the rift shows no signs of healing

By

The concept of a North–South divide, a line that dissects England, rendering the two halves economically, socially and culturally different, permeates English history. It also leaks into the very idea of Englishness. Some trace it as far back as 1066, when William the Conqueror rampaged north in ‘a mad fury’ (his own words) to control the unwieldy parts of his new kingdom. Ever since then, the story goes, North has suffered more than South, a phenomenon that has inevitably led to a raft of stereotypes. ‘The Northerner has “grit”, he is grim, “dour”, plucky, warm-hearted and democratic; the Southerner is snobbish, effeminate and lazy…’ wrote George Orwell in The Road to Wigan Pier, that classic tale of moving from a fairly prosperous London to an unfamiliar and downtrodden North.

Today, the notion of a North–South divide is still vastly important. Politicians promise to tackle it, academics grapple with it, authors capitalise on it, people complain about it. But how bad is it really?

In some respects, very bad. When it comes to health, education and transport in particular, the North has reason to complain. Since 2010, life expectancy has increased in London relative to other parts of the country. In contrast, it has improved least in the North East and has actually fallen in the most deprived parts of that region. According to the Office for National Statistics, between 2016 and 2018, Richmond-upon- Thames had the highest male healthy life expectancy at birth in the UK, at 71.9 years. This was 18.6 years longer than males in Blackpool, where it was only 53.3 years. In general, life expectancy at birth was highest in the four most southerly regions of England for both males and females. Much of this inequality was caused by higher mortality from heart and respiratory disease, and lung cancer in more deprived areas.

People also have a higher chance of dying prematurely (defined as death before the age of 75) in the North than the South. ‘Examining data on all deaths in England from 1965 to 2015, we found a 20 per cent higher risk of dying aged under 75 in the North,’ explains Tim Doran, a professor of health policy at the University of York. ‘Between 1965 and 1995, this gap narrowed, with health in the North slowly catching up with health in the South, but this convergence stopped in the late 1990s.’ Over the entire 50-year study period, mortality rates in the North were always at least 15 per cent higher than in the South – equivalent to an average of 38,000 excess deaths in the North every year.

This divide partly comes about simply because there are more poor areas in the North than in the South. But that’s not the full picture. Even after adjusting mortality rates for deprivation, a substantial divide remains, suggesting more deep-seated structural issues. ‘If you go back over the past 50–60 years in terms of premature deaths in the North, it’s over and above what you would expect,’ says Doran. ‘There seems to be an additional risk factor of being in the northwest and the northeast of England.’

Education is also a particular bugbear and once again, more than just poverty is at play. Children receiving free school meals in London are at least twice as likely to go to university as children receiving free school meals elsewhere in the country, with the exception of the North West and the West Midlands. ‘There are deeply ingrained structural issues,’ says Olivia Blake, the Labour MP for Sheffield Hallam. ‘We really don’t get enough money for education. We get less per head than a lot of the other major cities and it’s hundreds of pounds disparity. That really comes out in our GCSE results. So we still have quite a lot of difficulty getting a good amount of kids to get Cs at GCSE.’ The 2015–16 report by the government’s chief inspector for education was particularly stark in this regard, noting that while secondary schools had improved overall, ‘the gap between the North and Midlands and the rest of the country has not narrowed, in fact, it has widened slightly.’ It went on to state that ‘this year, there are 13 local authority areas where every secondary school inspected is either good or outstanding, and all in London or the South East.’

And then there’s transport, considered so bad in the North that it’s almost a joke. ‘We’ve had, I think, six ministers for transport come up to the North and promise new train carriages since 2010,’ says Doug Martin, course leader at the Carnegie School of Education, Leeds Beckett University. ‘We’ve got some secondhand carriages from the South starting to appear, which is good. But we’ve been literally using converted bus carriages for about 30 years between cities and towns in the North. Their lifespan must be ten years,’ he adds, referring to the much-maligned ‘Pacer’ trains: maximum speed 75mph.

What makes these divisions particularly stark is their extremity. Most countries have divisions, with the region around the capital city often more wealthy than other areas, but the UK’s seem particularly entrenched. Thinktank IPPR North’s State of the North 2019 report stated that ‘the UK is more regionally divided than any comparable advanced economy’. Researchers found that rates of mortality vary more within the UK than in the majority of developed nations, with places such as Blackpool, Manchester and Hull having mortality rates that are worse than those in parts of Turkey, Slovakia and Romania. As The Economist put it in a July 2020 article: ‘Other countries have poor bits. Britain has a poor half.’ The article went on to state that the North is as poor as the US state of Alabama or the former East Germany.

Where is the border?

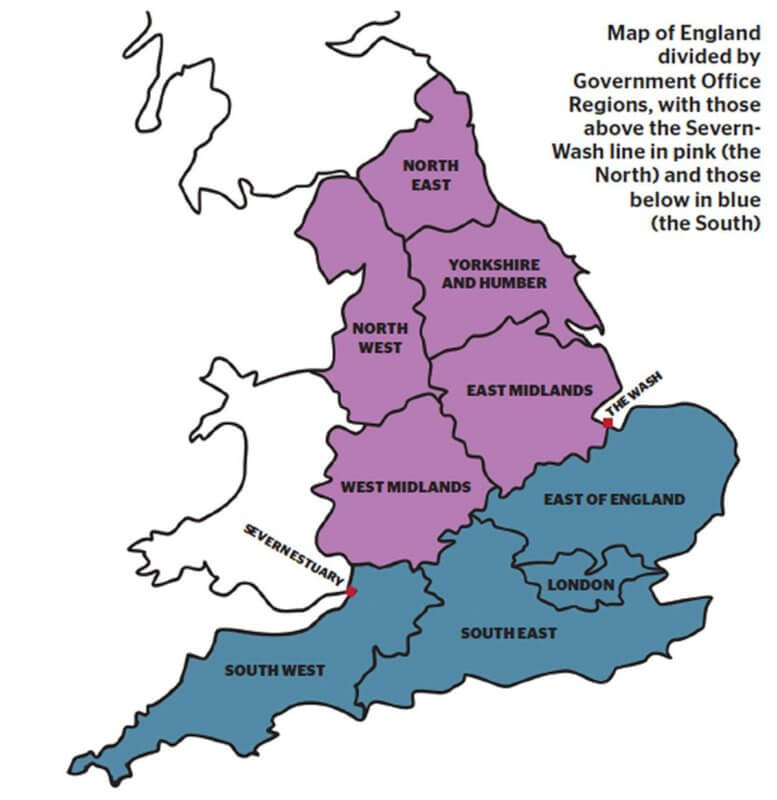

The dividing line between the North and the South is an arbitrary one, but that certainly hasn’t stopped people trying to identify it. (YouGov once had a go, based on the number of people who call their evening meal ‘dinner’ [southern], or ‘tea’ [northern].) While some regions are placed firmly in one camp or the other (Scousers know they are Northerners, Londoners know they are Southerners), plenty of others lie somewhere in the middle and the Midlands gets tossed about from map to map.

In 2017, Danny Dorling, then professor of human geography at the University of Sheffield, set out to draw a line based on a range of factors, including life expectancy, poverty, education and skills, employment and wealth. The resulting line runs diagonally across England, weaving through towns and villages and cutting through counties. It rests above Gloucestershire, Warwickshire, Leicestershire and Lincolnshire, and runs below West and Mid- Worcestershire, Loughborough, Scunthorpe, Cleethorpes and Great Grimsby.

Other attempts to draw similar lines have been more controversial. Mark Tewdwr-Jones, a professor at Newcastle University, caused some consternation in 2018 when he appeared on Radio 4 and divided the UK based on London’s sphere of influence, which, according to him, led to Leeds and York being defined as in the South.

The division that seems to be most commonly used in academic papers is the so-called ‘Severn-Wash’ line. Broadly similar to Danny Dorling’s line, although it respects county borders, it divides the population of England roughly in two, running diagonally from the Severn Estuary to the Wash – the rectangular bay located in the northwest corner of East Anglia.

Capital appreciation

Of course, many of these statistics raise one question in particular. Is there a North–South divide, or merely a London versus the rest of the country divide? London certainly sticks out for the sheer level of investment and infrastructure spending it attracts. Half of all foreign direct investment projects go to London and southeast England. This means that even though some areas of London have similar or worse levels of poverty than the North, by some metrics it still performs better. In fact, what London reveals is that poverty isn’t necessarily what defines the North–South divide. Some areas of London are extremely poor. According to a 2020 report by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, inequality is far higher within London than in any other part of the UK, with London overrepresented at both the bottom and the top of income distribution nationally. Measured after housing costs, 28 per cent of Londoners live in poverty, compared with 22 per cent across the UK as a whole.

Despite this, poor Londoners have better prospects when it comes to education and health than poor people in other regions. ‘Just the fact that we tend to concentrate power in and around the capital means that the further away from the capital you are, the worse the social circumstances tend to be,’ says Doran. ‘And health follows that pattern. What we’re seeing now is less a separation between North and South, and more between the capital and everywhere else.’

London certainly stands out infrastructurally speaking. Transport infrastructure spending for London in 2014 stood at around £2,500 per head, according to the Institute for Public Policy Research. The corresponding figure for the northeast of England was just £5 per head.

And in education things look better, too, setting London apart even from its wealthy southern neighbours. ‘London, although it’s much poorer than the rest of the south of England, is doing slightly better than the south of England at Key Stage 4,’ says Martin. ‘That’s partly because of a school-improvement programme called London Challenge, which was set up by Tony Blair. There has also been other research into why London may be doing better. One suggestion that’s very explosive is that the indigenous UK population don’t care much about education, whereas the migrant population in London see it as an opportunity. But there’s no clear evidence as to why London’s doing better with similar levels of poverty to the North.’

Mind the gap

The question of how to narrow the North–South divide (or the North–London divide, depending on which statistics you look at) has long plagued politicians. Schemes have come and gone, at a rate of almost one a year, but none have made a lasting impact. Specific efforts between 1997 and 2010 to reduce differences in life expectancy did begin to close the gap between the wealthiest and most deprived regions. However, this trend has now reversed.

The current government has pledged its own efforts. Boris Johnson has promised to ‘level up’ the economy, living standards and life chances across the country. The government has announced a review of the rules for deciding which public investments go ahead, with the intention of increasing the share going to areas outside of London and the southeast of England. Then there’s the Northern Powerhouse, the proposal launched by then-Chancellor George Osborne to boost growth in the north of England.

Many Northerners, however, remain unconvinced by these efforts. ‘In the North, we all laugh at the Northern Powerhouse. It’s just an absolute joke,’ says Martin. ‘Promises of improvements and investment. People in the North just laugh about it.’

Stay connected with the Geographical newsletter!

In these turbulent times, we’re committed to telling expansive stories from across the globe, highlighting the everyday lives of normal but extraordinary people. Stay informed and engaged with Geographical.

Get Geographical’s latest news delivered straight to your inbox every Friday!

For some, until we tackle the wide-ranging impacts of austerity – the era that saw local funding slashed dramatically, with the cuts arguably disproportionately hitting the North – it will remain impossible to lift up the poorest areas. ‘What local governments have been able to invest in has been really, really reduced,’ says Blake. ‘So all of the stuff that we used to do around business innovation has been stripped back. Really, until we fix that kind of underlying investment in public services, it’s going to be very difficult for local leaders to invest and shape areas so that some of the inequalities can be tackled.’

But it comes down to more than just funding. A report published by the UK2070 Commission, run by a former head of the civil service, Bob Kerslake, called for a long-term plan that, as well as a £10 billion-a-year fund, would see the development of an ‘MIT of the North’. It argued that Britain has an unstated policy in which spending on science, culture and administration is concentrated in the South.

The report also called for substantial devolution of power to the North and this more than anything, is the cause that unites Northerners. ‘We’ve always been fairly centralised,’ says Doran. ‘But now, more than 90 per cent of our public spending is controlled in Westminster.’ The State of the North 2019 report also blamed centralisation of power and lack of devolution for making the country more regionally divided than comparable nations, pointing out that 95p in every £1 paid in tax is taken by Whitehall, compared with 69p in Germany.

‘No other country has that degree of centralised control,’ adds Doran. ‘If you look at Spain, there’s a much greater degree of regional autonomy, where the regions have greater power to raise and spend taxes. Even the local authorities in England and Wales are beholden to Westminster, so they can only spend what Westminster gives them and their tax-raising powers through local taxes are actually quite strained.’

To a certain extent, a new era of devolution is already underway. There are now directly elected mayors in Greater Manchester, Liverpool City Region, Tees Valley, Sheffield City Region and the North of Tyne. Some – Greater Manchester mayor Andy Burnham springs to mind – are making quite a name for themselves. But, according to Jake Berry, Conservative MP for Rossendale and Darwen and former minister for the Northern Powerhouse, it’s still not enough. ‘We live in a far too over-centralised country and although some steps have been made to devolve power to regions and nations within our United Kingdom, that is all at the whim of Whitehall,’ he says. ‘I believe, and I think lots of people across the north of England believe, that actually, if you really are going to close this North–South divide, you have to look at transferring power, money and influence, which will then, in turn, help to generate the wealth to close the gap.’

Unlike many issues in today’s partisan politics, this push seems as though it could cross party lines. ‘I think that actually, there’s a real excitement around devolution and I think that we should continue to have those conversations, particularly within the Labour party,’ says Blake. ‘I think that there’s a real need.’

Not so grim up north

There is, of course, another side to Northern life and the desire to point out unfair regional differences can sometimes mask it. The stereotype of ‘it’s grim up north’ is surely a lazy one. Perhaps what best defines the North is a sense of pride and a determination to endure. Adversity, after all, can build community.

‘The northern area doesn’t really exist in any government-acknowledged way,’ says Berry. ‘But people who live in the North know what it is to be a Northerner, and that’s really strong. I would say it’s as strong as people who are Scottish feel a Scot, or people in Wales feel Welsh. Place is really important to people.’

This sense of pride in place not only fosters a sense of community but contributes to a thriving cultural scene. Contrary to the common attitude that people wanting to work in the creative industries necessarily flock to London, for some this is far from the truth. Fiction author Ben Myers, who was born in Durham in 1976, has experienced both sides of the country, having spent nine years living in London. Now back in his home county, he doesn’t see the capital as a particularly friendly place for creatives.

Subscribe to our monthly print magazine!

Subscribe to Geographical today for just £38 a year. Our monthly print magazine is packed full of cutting-edge stories and stunning photography, perfect for anyone fascinated by the world, its landscapes, people and cultures. From climate change and the environment, to scientific developments and global health, we cover a huge range of topics that span the globe. Plus, every issue includes book recommendations, infographics, maps and more!

‘My experience as a writer is that it’s much easier and more enjoyable to exist as a creative, artist or writer in the north of England. I think the narrative is that the North is hard done by and we’re deprived and we don’t get help. And I’ve possibly said as much in pieces in the past, but there is support up here. There are networks and grants, and there is funding. And it’s just much easier to live here. I can exist on half the outgoings that I had when I lived in London. So if your rent or your mortgage is half, that means, theoretically, you only have to do half as much work, which means it frees up a lot of time to create.’

When it comes to income (but not wealth), this is partly backed up by the statistics. According to the Institute of Fiscal Studies, if measured before housing costs, median household income in London is around 14 per cent higher than the UK average; measured after, it’s only one per cent higher. London’s house prices make it far from desirable for much of the population.

Devolve, evolve

Today, the North is bracing itself for the effects of Covid-19. Already it is clear that the region is suffering from higher case numbers. Hospitalisation rates of people with coronavirus for the week ending 4 October were 7.3 per 100,000 in the North West, and only 1.7 per 100,000 in London. Longer term, the pandemic will likely hit Northern economies harder as well, partly because it has a higher proportion of jobs in hospitality and leisure. But, if anything, these difficulties are likely to exacerbate calls for more autonomy, even if that autonomy won’t be given easily. At the time of writing, Andy Burnham was battling the government over its proposed local lockdown and Covid-19 support package. Local mayors can undoubtedly be a headache for central government, but Northerners believe that the right to be headache is a right they should have.

‘Whatever the government’s view is, and I guess the government’s probably going a bit cold on devolution, given the current fights with these mayors – it’s going to happen,’ says Berry, who recently set up a new grouping of northern Tory MPs designed to put pressure on the government to fulfil its promises of levelling up. ‘Like we found with Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, it’s a one-way street. You can’t go backwards. I think, out of this Covid crisis, there will be a cross-party alliance to say, let’s rethink Britain. I think this is the time to do it.’