Hugh Francis Anderson reports on a centenary expedition to Jan Mayen island in the Arctic Ocean, site of the northernmost active land volcano

Words by Hugh Francis Anderson, Photographs by Hugo Pettit

Flicking through a 100-year-old edition of the Geographical Journal in the Members’ Room of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) in Kensington a few years ago, I found an article about Jan Mayen island, a remote volcanic outcrop in the Arctic Ocean. I had recently returned from a research trip to the Arctic where, coincidentally, the captain of the yacht I was aboard had told me about this little-known outpost.

The article was a report on the first British expedition to the island in August 1921, led by Sir James Mann Wordie, the geologist and chief of scientific staff with Ernest Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Arctic Expedition, 1914–1917 (he later became president of the RGS). The expedition’s goal was two-fold: to undertake the first geological study of the island and claim the first ascent of Mount Beerenberg.

I called my expedition skipper, Norwegian explorer and marine scientist Andreas B Heide, and we soon decided that, as it was 18 months away from the centenary of the first trip, it was time to mount another.

The bloody age of whaling

Look on a map, and you’ll likely miss the island of Jan Mayen. With a landmass of just 377 square kilometres, it lies on the southern edge of the Arctic Ocean, between the Greenland and Norwegian seas. A volcanic growth sprouted from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge as recently as 500,000 years ago, it sits in more than two million square kilometres of open ocean. A short isthmus separates the low-lying south from the dominating north, where the world’s northernmost sub-aerial active volcano, Mount Beerenberg, rises more than two kilometres out of the ocean. Beerenberg is comprised of 20 glaciers and is topped by a one-kilometre crater rim.

At the commencement of European Arctic whaling during the early 17th century, the British and Dutch battled for hunting grounds. While some believe Henry Hudson discovered Jan Mayen in 1607, the first verifiable account was in 1614 by Englishman John Clarke. At the same time, three Dutch whaling ships arrived, one of them captained by Jan Jacobsz May, after whom the island is named.

Susan Barr, a former cultural heritage advisor on the Arctic to the Norwegian government, explained: ‘The market for whale products was large in Europe and once the Dutch discovered Jan Mayen, with the numbers of whales nearby, it was natural for Dutch whaling companies to occupy the bays there with their train oil (bowhead blubber) boilers. The whaling started very successfully but petered out around 1642.’

Whaling logbooks of the time record the presence of thousands of bowhead whales. The bowhead population in the Arctic is thought to have been in excess of 46,000, thriving on the abundant plankton in the nutrient-rich meltwater from the Greenland Ice Sheet. However, after just 22 years, bowhead stocks were so depleted that Jan Mayen became unprofitable for the Dutch. By 1850, bowheads in the Arctic had been hunted to near extinction. While the subpopulation around Greenland remains endangered, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the global population has rebounded to an estimated 10,000 individuals.

The Austro-Hungarians first undertook significant mapping of Jan Mayen during the First International Polar Year, 1882–83. While they spent almost a year on the island, their party was without a geologist, and failed to reach the summit of Mount Beerenberg. It was a combination of these two factors that inspired Wordie and his team (JL Chaworth-Musters, botanist; TC Lethbridge and WS Bristow, naturalists; and Paul-Louis Mercanton, glaciologist) to join a Norwegian party led by Hagbard Ekerold, who aimed to establish the first weather station on the island.

By 1930, Jan Mayen had been annexed by Norway. It was a source of much interest during the Second World War and has since had a continuous Norwegian military presence. A meteorological station and a ground station for the Galileo satellite navigation system are also located there. The island’s north is now a protected nature reserve with significant restrictions to maintain its fragile ecosystems. It’s seldom visited.

Modern-day research

Captain Heide uses the ship Barba as a research and storytelling platform, with a message of conservation that focuses on whales as ambassadors of the ocean. I joined him in 2019 as part of his Arctic Whale expedition to study the effects of microplastics on Atlantic whale species in Iceland’s coastal waters. It made sense, therefore to combine the centenary expedition with more research, namely the 2021 Arctic Sense expedition – a collaborative, four-month, 3,000-nautical-mile scientific and communications voyage to the polar Atlantic with a rotating team of scientists and storytellers.

‘Marine research has a great importance for the general life-support function of the ocean and for sustainably using the ocean to feed an ever-growing population,’ says Heide. ‘Marine research in the Arctic is of special importance as the ecosystem is undergoing rapid change with retreating ice as a result of global warming. The retreating ice also brings with it an increased opportunity for commercial exploitation of the region, making it even more important to document what we are at risk of losing.’

In partnership with the research group Whale Wise, and with the support of the University of Stavanger and the University of Iceland, a comprehensive research plan has been established to gather as much information about Arctic and sub-Arctic cetaceans as possible.

‘Our aim is to monitor Arctic ecosystems, focusing on whales, in an unobtrusive way,’ Whale Wise cofounder Tom Grove explained. ‘Arctic ecosystems remain poorly characterised. Across large parts of the Arctic Sense route, the occurrence, distribution and diversity of cetaceans are virtually unknown.’

Photographer and filmmaker Hugo Pettit and I met Heide in Longyearbyen, the world’s northernmost settlement with a population greater than 1,000 and the largest inhabited area of Svalbard, Norway. He had just completed a circumnavigation of Svalbard. Our five-person crew was completed by sailors Jaap van Rijckevorsel and Annik Saxegaard Falch, and we set off on the 1,200-nautical-mile journey across the Greenland and Norwegian seas to Jan Mayen and then on to Shetland.

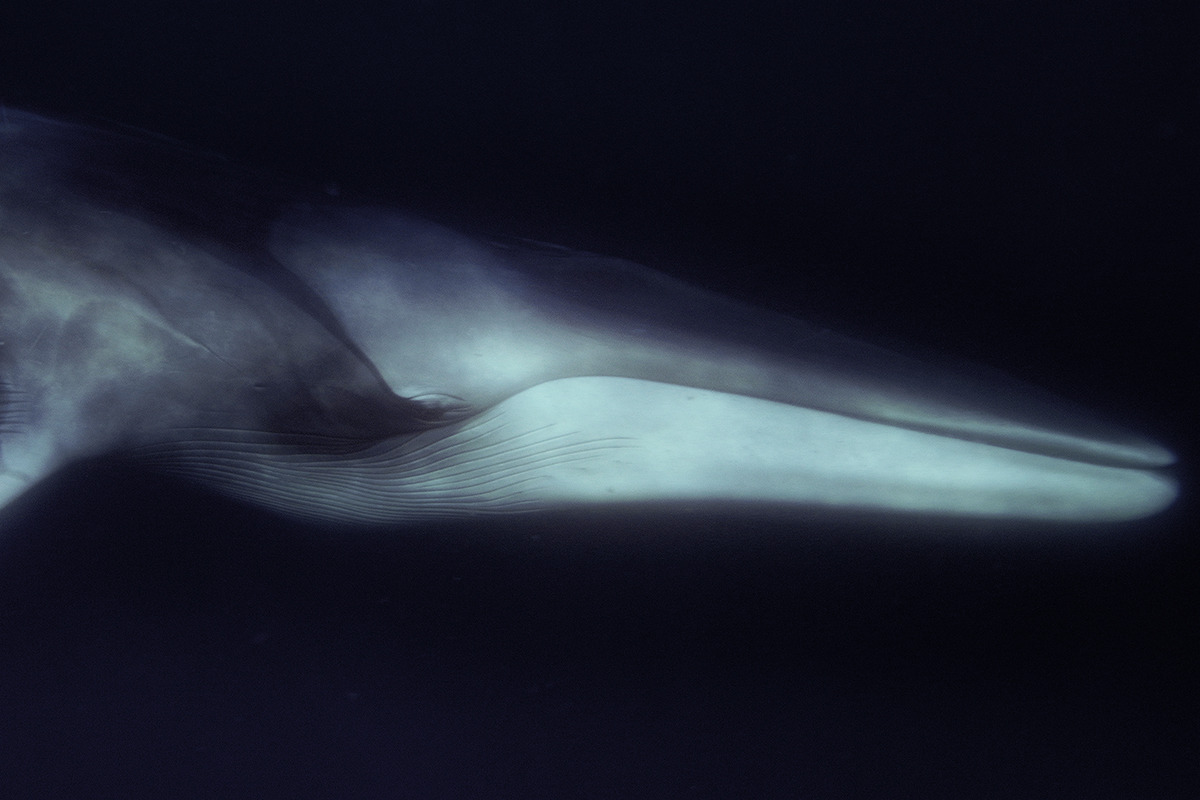

I felt the onset of autumn in the air, but the winds were gentle and the water calm as we sailed out of Isfjorden and into the Norwegian Sea. Within 24 hours, Rijckevorsel spotted a large blow (whale breath) on the horizon. At four to five metres high, it was likely from a fin whale. We changed course and sailed in its direction. More blows appeared. Groups of 10–20 fin whales surfaced beside us. The deep exhalations and inhalations resounded in the air like a symphony. The whales’ movements at the surface were slow, betraying their great size; fin whales are the world’s second-longest whale species.

Heide and Pettit readied themselves and then entered the water. From the boat, I could see large pockets of bubbles rising to the surface around a bait ball, on which the fin whales were feeding. It was a rare chance to observe fin whale ‘bubble net’ feeding.

‘Fin whales are hard to observe underwater, as they are shy and fast-moving, and I have not previously seen any underwater footage of such behaviour,’ said Heide.

We remained with the fin whales for several hours before we resumed our crossing to Jan Mayen. With the wind building but manageable, we passed over the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, 80 nautical miles off the coast of Svalbard. The ridge is an underwater mountain chain that runs the entire latitudinal length of the Atlantic; its numerous peaks and trenches are hotspots for deep-diving cetaceans. While studied in detail to the south of Iceland, much less is known about the remote northern portion leading to Jan Mayen and beyond.

‘This region consists of a series of ridges, troughs, canyons and seamounts,’ says Grove. ‘Such extreme topography is likely to result in upwelling, and we might expect the northern part of the ridge, a complex network of topographic features ranging from 1,000 to 3,000 metres deep, to show a similarly high diversity and occurrence of cetaceans.’

Here, Heide deployed the towed hydrophone array, designed to pick up both low- and high-frequency vocalisations. When interfaced with the PAMGuard system and visualised on a spectrogram, the detection of cetaceans can be documented in real-time. Within minutes, Heide heard and saw the familiar clicks of sperm whales. The hydrophone remained in the water recording for more than 48 hours. Once processed by the Whale Wise team, the data should tell us more about cetacean occurrence and distribution in the region.

Ascending the volcano

Alongside the whale research, the centenary climb of Mount Beerenberg was firmly in our minds from the outset of the expedition, but it raised two questions. First, due to climate change and glacier degradation, would it still be possible to reach the summit using the 1921 route? And second, could we collect glaciological data for analysis? When the Wordie party reached the summit in August 1921, the route began at the base camp near Eldste Metten, the weather station built by Ekerold. They travelled west up Ekerold Valley to an advance camp at the base of the frontal moraines of South Glacier. The summit was achieved by travelling up South Glacier to the crater rim. By combining 3D-mapping software, which was used to plot the 1921 route as accurately as possible, with current satellite imagery, we were able to set a provisional route.

After five days at sea, it was with bated breath that we waited for the clouds to rise from the peak. From our anchorage in the north, we studied the mountain, and our first question was quickly answered. The crevasses towards the top of South Glacier, which we estimated to be between eight and 12 metres wide, would be impassable: it wouldn’t be possible to reach the summit using the same route as the Wordie party in 1921. While we were deflated, this came as little surprise. Globally, glaciers are losing more than 30 per cent more ice and snow each year compared to 15 years ago, with anthropogenic climate change the most likely cause. On Jan Mayen, our observation of the increase in crevasses on South Glacier is further evidence of this pattern and as such, it offered an opportunity to collect samples to help further understand what might be contributing to the degradation.

Biological darkening is one of the causes of glacial melt and the Deep Purple research project aims to discover more about the growth and causes of algal blooms on the Greenland Ice Sheet. Due to the darkened pigmentation of snow and ice algae, these blooms absorb solar radiation, which subsequently causes the glacier to melt at an increased rate.

Professor Martyn Tranter, who heads the research, explained: ‘The amount of meltwater the Greenland Ice Sheet is producing has accelerated over the last 20 years. That coincided with the growth of a dark band along the western margin of the ice sheet called the Dark Zone, which is formed by the annual growth and blooming of purple-pigmented glacier ice algae. Deep Purple is trying to get all the data to determine how much the Dark Zone will expand over the coming decades.’

Data from other regions are also valuable to determine whether similar melting effects occur elsewhere. On Jan Mayen, testing for snow and ice algae had never been undertaken. So, with protocols and equipment compiled, we aimed to collect samples from South Glacier to learn more.

While the original expedition’s route would be impossible for us, Wordie had proposed a secondary route that followed the southwest buttress to the crater rim, which our observations suggested was still achievable. Our approach began from the south, across the isthmus, some 20 kilometres away from Eldste Metten. Even here, on this remote Arctic outpost, the onyx sand is littered with plastic and fishing debris. Such is the island’s remoteness that we came across the skeletal remains of a bowhead whale hunted more than 400 years ago. The ruins of Eldste Metten appeared between the volcanic outcrops, its structure a fragile shell of the building erected 100 years ago.

We began our ascent during the night and by daybreak we had reached the base of South Glacier and broken above the low-lying cloud. However, our favourable weather window closed rapidly, and a blizzard with winds of more than 40 knots hammered us as we approached the final ascent to the crater. The conditions were so poor that we only knew that we had reached the summit thanks to our GPS.

As the blizzard eased and the clouds lifted, the late-afternoon light shone off South Glacier. Around, large, darkened patches of snow appeared, some pink, some red, some green. We figured that they must be patches of snow algae, so we collected some samples on our descent. These have since been examined by Professor Alexandre Anesio, a principal investigator on the Deep Purple team. Anesio discovered a large amount of red snow algae, alongside green snow algae, cryoconite material, cyanobacteria and flagellates. But he was surprised by the absence of ice algae.

‘Very interestingly, I could not see any ice algae in any of the samples,’ he told us. ‘But, because of the biomass of snow algae that you have in some of the samples, that is going to melt some of the snow, expose the bare ice, which will then be colonised by the ice algae, and which is then going to generate the further darkening of the ice. These samples are important because they show how widespread the colonisation of snow algae is across different glaciers worldwide.’

The gruelling approach and ascent took 37 hours, and we travelled almost 70 kilometres. Such is the hostility of this Arctic Ocean outpost that just hours after returning to Barba, an incoming weather front forced us to set sail or risk being stranded at anchor for the coming week.

Time for reflection

Seven days later, we glided into Lerwick Harbour in the Shetland Islands, exhausted from the unrelenting seas and headwinds that pushed us so far off course that we almost reached mainland Norway. However, the last leg of the journey had offered a time for reflection and a discussion on the nature of contemporary exploration.

In a modern interpretation of a 100-year-old expedition, our journey had collected data to help better understand the state of Arctic ecosystems and provided a chance to record the rarely seen feeding behaviour of fin whales, but it also highlighted our personal search for adventure. Curiosity and the pursuit of knowledge drive us to seek adventure. And while the context has certainly changed, these elements bond us across time.

For more information on the research platform Barba, please visit barba.no

Hugh Francis Anderson is a writer specialising in adventure and the environment. Visit hughfrancisanderson.com