Much of Cambodia’s cultural and artistic heritage was destroyed during the brutal years of the Khmer Rouge, but today, a music school for orphans is passing on traditional knowledge

Words by Laura Fornell, Images by Oscar Espinosa

At three in the afternoon, the intense heat in the city of Kampot in southern Cambodia has almost completely cleared the streets of people. In an avenue in the centre of the city, an enveloping melody can be heard over the background urban thrum. Escaping from a garden, the sounds of string, wind and percussion instruments subtly interact, generating an atmosphere of calm in the already peaceful city.

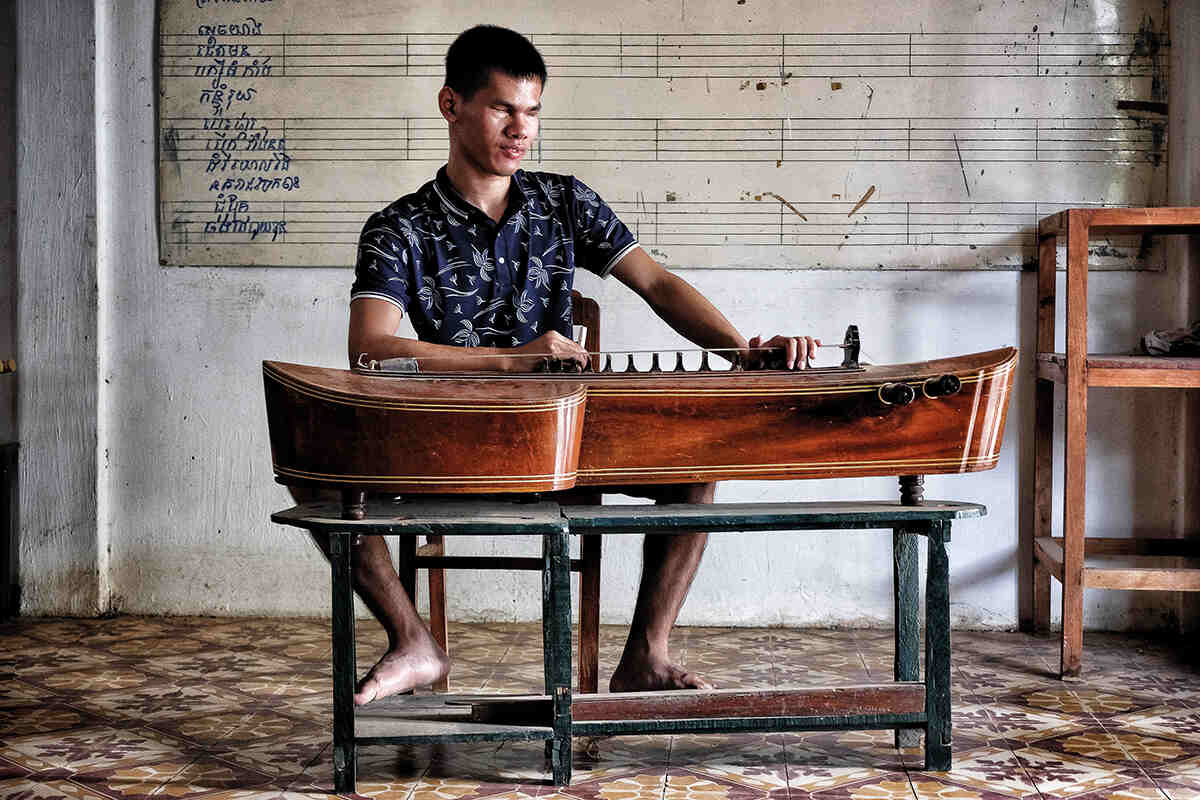

The music stops. Then, after a brief murmur, the same song begins to play again. Master Ros Samoeun has just given the order to his four students to start over. Without a word, the young people, serious, concentrating hard, begin to play again. Chourn Reach sets the melody with his tror, a two-stringed bowed instrument; Saron occupies a large part of the music room with a takhe, a three-stringed floor zither in the shape of a crocodile; Iem Rokhthai plays a type of flute called a khloy; and Kan Prak is in charge of percussion with the skor, made up of two small drums.

The small Mahori ensemble – a type of traditional Khmer music made up of ancestral Cambodian instruments – is rehearsing at the Khmer Cultural Development Institute (KCDI), an NGO that emerged in 1994 with a dual objective: the care of orphaned children and the preservation of traditional arts, whose continuity was endangered following the killing of almost all of the country’s artists during the genocide perpetrated by the Communist regime of the Khmer Rouge (1975–79). For almost three decades, hundreds of children and vulnerable youths have passed through the centre, where they’ve found refuge and the training necessary to become professional artists. KCDI currently houses ten orphaned children between the ages of five and 17, as well as four blind youths between the ages of 17 and 24.

‘It gives me great pleasure to transfer my knowledge to these youths and to think that they will continue to preserve the traditional Khmer arts,’ says Loak Kru Ros Samoeun, the teacher today. Having survived a Khmer Rouge prison camp, he became a professor at the Royal University of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh. In 1997, he joined the KCDI project, where he has been teaching Mahori music to the children, many of whom have gone on to become professional artists.

In 2015, the institute began to provide Mahori music lessons for blind children as a form of therapy and vocational training. ‘I have never taught blind students before and it has been quite a challenge for me. They are very disciplined and I make them do a lot of repetitions so they learn the melodies. As a teacher,

I am very proud of them. I think they are talented and will be able to dedicate themselves to music and help their families,’ Samoeun says from the small music classroom. ‘When they return to their villages, they will be able to play and sing in ceremonies, and they will also be able to teach other musicians the traditional smot songs – sung poetry, performed mainly at funerals – that they are learning here, thus ensuring that they do not fall into oblivion.’

The next day starts early. At around 5am, students begin to leave their simple rooms overlooking the garden to go to the communal bathrooms, while the dogs that they keep as pets stretch themselves and then chase them for their first pats of the day. The four blind youngsters and the ten orphaned children go to school in the mornings and then, in the afternoons, receive lessons in traditional Cambodian music and dance, some of them taught by former students who’ve passed through the centre and now devote their lives to traditional Cambodian arts.

After the students have eaten breakfast together, peace returns to the centre. After a while, the music of a khloy begins to waft from a dormitory. Saron and Iem Rokhthai are 24 years old. The oldest of the four blind youths at KCDI, they dropped out of high school and now spend their days together at the centre, where their whole life revolves around music. They arrived at KCDI at the age of 17, at which point they first came into contact with a musical instrument.

Today, Saron plays the takhe, the khloy and the tror. When asked how he sees himself in a few years, he answers without hesitation: ‘I want to be a musician and a music teacher. In fact, I have already got some sporadic jobs and have performed at marriage ceremonies and the odd funeral.’

Iem Rokhthai plays the khloy and the skor. A year ago, he started to practice with the peiar – another type of flute. He’s also very clear that he wants to continue to study music and become a professional musician in order to earn a living and be independent.

Chourn Reach, 23, plays the tror and the chapey – a long-necked guitar with two strings. He’s a final year law student at Kampot University, where he attends classes every Saturday and Sunday. From Monday to Friday, he also attends computer classes at a nearby training centre, where he’s accompanied by one of the teenagers who is also hosted at KCDI. When he’s not in class, he spends the day in his room studying and practicing his instruments. ‘When I graduate, I will have to go to Phnom Penh to pass the bar exam to be admitted to the Bar Association of the Kingdom of Cambodia, but after that, I want to return to Kampot to work as a lawyer, and I would also like to stay connected with music,’ he says.

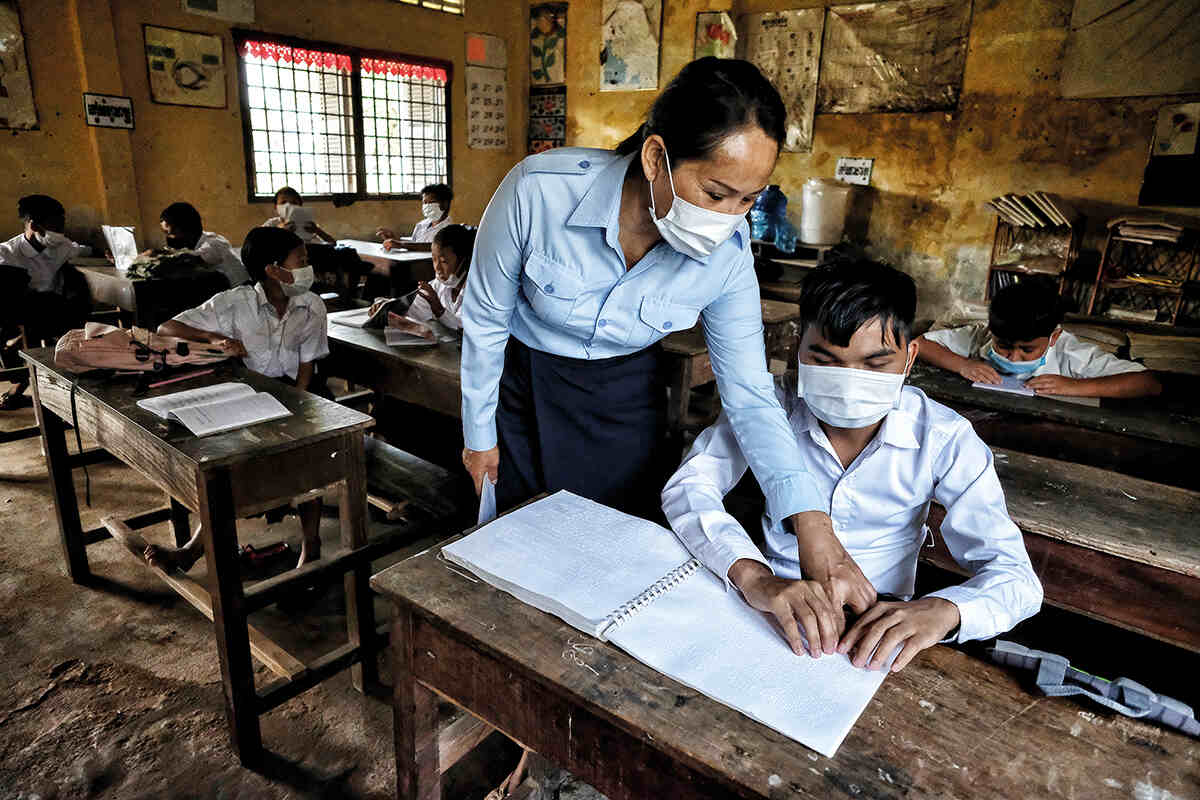

The youngest of the four, 17-year-old Kan Prak, is also certain that he wants to pursue a career in music. He plays the skor and the khloy, and is passionate about singing and reciting smot poems. Every day, between 7am and 11am, he attends the nearby public school, where he is in sixth grade, the final grade of primary school, with ten other younger boys and girls, aged nine to 12. ‘I’m like their big brother,’ he says with a chuckle as he settles into a desk in the front row, right across from that of his teacher, Naybuntho, 49, who is braille-trained and is teaching him to read and write.

‘He is a good student. Although braille still seems complicated to him, he is trying hard to learn and always comes to school motivated,’ she says. While the other children are writing down the lesson in their notebooks, Kan Prak begins to read the lesson aloud, running his fingers across the braille sheet in his notebook under the watchful eye of his teacher, who corrects him from time to time.

From 11am onwards, the students gradually return from school and all get together again for lunch. They are like a big family, the older ones helping the younger ones to finish their chicken with rice. After eating, everyone retires to rest, some in their rooms and others simply lying in hammocks in the garden under the shade of the trees.

A little before 2pm, the four blind youngsters cross the courtyard to the small music room, where Loak Kru Ros Samoeun awaits them. For the next two hours he will teach them Mahori music. ‘This is the time of the day I enjoy the most,’ Saron confesses, sitting in front of his instrument before the lesson begins. His three classmates nod in agreement as they take their places in the classroom: Saron stands on the left, Iem Rokhthai in the centre, Chourn Reach on the right and Kan Prak behind the other three. Having tuned their instruments, they begin to practice a piece of traditional music, following the instructions of the teacher, who makes them repeat fragments of the song, sometimes all together and sometimes separately, until they achieve a perfect execution of the piece.

Culture and the Khmer Rouge

The brutal Khmer Rouge regime ruled Cambodia, under the leadership of Communist dictator Pol Pot, between 1975 and 1979, after which followed 20 years of instability and civil war. Pol Pot’s fanatical goal – to create a classless agrarian society and in doing so ensure a Cambodian ‘master race’ – led to the deaths of more than two million of the seven-million-strong population, either by direct execution or from starvation, disease or overwork.

The regime also oversaw the destruction of culture, targeting artists and intellectuals in particular. According to the Cambodian Living Arts organisation, 90 per cent of the country’s artists didn’t survive the Khmer Rouge regime and its artistic heritage was in danger of being lost forever.

Cambodia has a long and rich cultural history that dates back to before the Middle Ages. During the golden age of the Khmer Empire (between the ninth and 13th centuries), arts and culture became integrated into Cambodian society through religion, rites and customs. Under the Khmer Rouge, however, private property, money, religion and traditional culture were abolished; an estimated 90 per cent of schools were destroyed, along with numerous libraries and temples. Artworks and monuments were destroyed and ritual practices such as dance dramas and family ceremonies were banned, replaced by propaganda rituals.

Ethnic minorities such as the Cham Muslims and ethnic Vietnamese groups also suffered severely. In 1975, the Cham constituted the country’s largest minority group and more than 100 mosques and religious schools existed around the country. According to a 2021 study in the International Journal of Transitional Justice, by the time the Khmer Rouge regime fell in 1979, an estimated 130 mosques had been demolished. Khmer Rouge cadres destroyed Qur’ans and other Islamic texts, and confiscated or destroyed traditional modes of dress such as the sarong, fez and makhma.

The country is still grappling with the legacy of the Khmer Rouge. Only three of its leaders have ever been sentenced while many former regime personnel remain in power, including Prime Minister Hun Sen, leader of the Communist Cambodian People’s Party since 1985. While the country has made great strides in education, UNICEF notes that ‘overall, large numbers of girls and boys remain out of school at all levels of education, from early childhood through to adolescence’.

Nevertheless, work to restore and protect culture is ongoing. Founded in 1998 by genocide survivor and musician Arn Chorn-Pond, Cambodian Living Arts spent its first decade focusing on endangered performing art forms and rituals. It says that for the past 20 years, both Cambodia and its arts scene have developed rapidly. Today, it works to help talented people to build and develop careers in the arts while also working to get more arts and culture education into Cambodian public schools, and to increase performance opportunities for Cambodian artists.

After a short break, they put their instruments aside and sit down on the floor in front of four chairs that the teacher has set up for them as desks, each provided with several blank sheets of paper, a slate and a stylus for writing in braille. They resume their lessons on smot.

Mobile phone in hand, the four youths search for a song on YouTube. After listening to it, they transcribe it into braille and then perform it in front of the teacher and their classmates. ‘Today we have turned to YouTube to look for the poems, but other times it is the master who teaches us a smot song, interpreting it several times so that we can retain the lyrics,’ explains Chourn Reach as he glides his fingers over the braille sheet containing the lyrics of the song he is about to perform, accompanied by his chapey. At the end of the class, after Kan Prak is applauded for his passionate performance, they leave in single file, accompanied by the teacher, and return to their rooms, where they leave their instruments and prepare to go to dinner.

Also known as Cambodian Buddhist chanting, smot is usually performed at funeral ceremonies by a solo singer. Its poetic texts often refer to the life and teachings of the Buddha, traditional Khmer stories and religious and moral principles such as gratitude to parents and elders. ‘For me it is very important to perpetuate smot and that this centuries-old genre that the Khmer Rouge wanted to destroy by killing so many masters does not disappear,’ says Loak Kru Ros Samoeun. ‘It requires a lot of practice to acquire the performance skills and in-depth knowledge of the repertoire that has been passed down from generation to generation, and although they still have a lot to learn, they will be in charge of transmitting this traditional musical and social and liturgical expression to the next generation tomorrow.’