Chai Vasarhelyi speaks on the fascinating resilience of humans and their ability to persevere for her latest film ‘Endurance’

Interview by Victoria Heath

In 1914, polar explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton undertook what may be considered the greatest survival story ever told. In a legendary feat of perseverance, Shackleton kept a crew of 27 men alive for twenty months in brutal Arctic conditions, after the loss of their ship in frigid pack ice.

His initial mission – to be the first to traverse Antarctica from coast to coast – failed, leaving Shackleton and his men alone on the ice of the Weddell Sea. Surviving on a diet of penguins, seals, their sledge dogs – and eventually limpets and boiled seaweed – all crew survived after perilous voyages to Elephant Island and the island of South Georgia to find help.

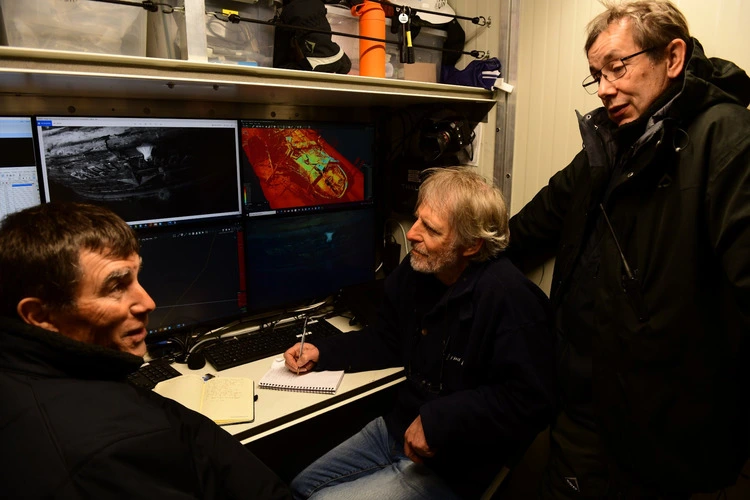

Over a century later, a team of modern-day explorers set out to find the sunken Endurance ship, using the latest cutting-edge undersea search technology to aid their mission.

From National Geographic Documentary Films and directed by Chai Vasarhelyi, Jimmy Chin and Natalie Hewit, Endurance tells the inspiring stories of these two landmark expeditions, bound by their shared grit and determination.

We spoke with Oscar-award-winning director Chai Vasarhelyi – whose other films encapsulate true human resilience, including Free Solo (documenting the nail-biting journey of climber Alex Honnold as he attempts to scale the 3,200-foot El Capitan in Yosemite National Park without a rope) – on Endurance, and how the documentary’s title is far more than the name of Shackleton’s ship, but a testament to the wider resilience of human spirit in past and present.

What brought you to the story of Ernest Shackleton and his crew?

Jimmy and I have always been fascinated by the Shackleton story. It is the greatest story of survival and exploration ever told. It’s such a testament to what leadership can be and how some of your greatest successes could also be your greatest failures.

When they found the Endurance boat in 2022, we saw it immediately as an opportunity to revisit the Shackleton story and use new tools that we’d been interested in.

For most films, when you finish them, I liken it to putting lipstick on, or putting on your nice dress. But for Endurance, I had visceral goosebumps when I finally watched the finished film. Suddenly, with all the tools put together – the sound design, the colour treatment of Hurley’s original footage – it really dawned on me that what I was watching was the real thing.

Endurance intertwines two stories together: that of Shackleton’s historical expedition, and the Endurance22 mission which eventually found the ship’s wreckage. What did you think that you got from combining both stories together?

The two stories speak to each other, because they both get to the idea of this fundamental human condition: of having the audacity to dream, and also the strength, tenacity, grit, ingenuity and diligence to see it through.

For example, I never would have imagined that a main motivator for Dr John Shears [the Expedition Leader of the 2022 mission] becoming one of the greatest British Antarctic explorers was the fact his grandmother didn’t get to see the world. Or equally, it was moving to see that Nico Vincent [the Expedition Sub Sea Manager of the 2022 mission] – who had suffered the terrible and painful loss of his wife – finally got back out on the ice because of his motivation and desire to contribute to the expedition.

So I guess it’s that: I’m interested in the questions that drive people to pursue these ambitions. In this time when we’re all so plugged in and connected to our devices, these two stories are really a reminder of ingenuity and perseverance and also how exciting our outside world is.

What challenges did you face filming in such extreme conditions?

Filming under extreme conditions is very much Jimmy’s – my filmmaking partner’s – expertise. But we actually weren’t on the 2022 expedition since we were filming for Nyad [Chin and Vasarhelyi’s documentary on a marathon swimmer’s attempts to become the first person to swim from Cuba to Florida]. So Natalie Hewit was filming on the boat instead.

I think Natalie’s main constraint was the sheer size of the boat, as well as the limitations of how many crew we could have filming. Filming also took place during Covid – in the first two weeks, everyone was wearing masks. You were only allowed to have a particular amount of people in a certain size room, so I think you could feel that in the footage, and we really worked around it.

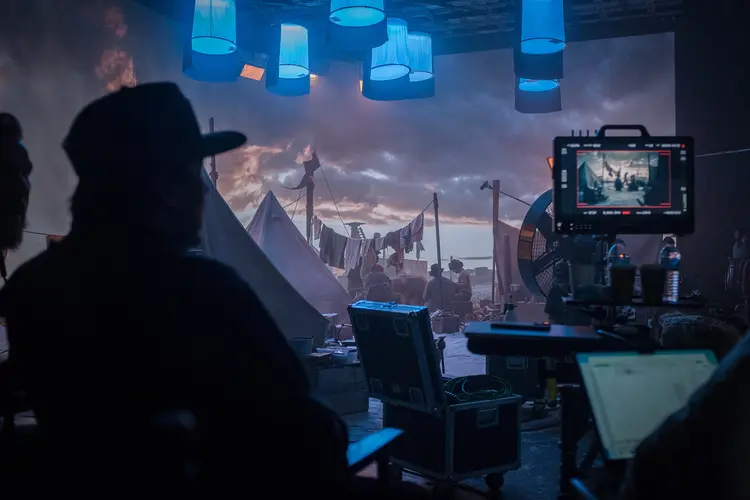

We did reenactments and used other people’s footage from other films, because it’s part of the overall story itself: Shackleton’s story has been told over and over again for so many years, and each retelling is a little different.

What was your favourite part of Endurance?

The 3D imaging that the Sabertooth was able to take of the Endurance wreckage – and that Nico pioneered – is just astonishing. I’m struck by the details it shows, from the boot buckle to the linoleum on the shipwreck. It’s one thing to see photographs of artefacts and another thing to hear people talk or write about them. It’s completely different to see three miles under the ocean, an actual image of a 110-year-old artefact.

Another thing I was really pleased to include in Endurance was finding out and including the three women who showed up for Shackleton’s expedition and wanted to go.

Do you feel that you’re any closer to understanding why humans explore, not just in Shackleton’s case – as a brilliant testament to exploration at its greatest – but also as tourists and everyday people?

I think it’s about belonging and the idea of wanting to connect and be understood.

Shackleton was an outsider. He was Irish. He didn’t go to the fancy schools. He wasn’t part of the Royal Navy, and he was a Merchant Marine. But clearly there was some force of character behind him that made him want to prove himself.

Human exploration is one of those amazing parts of the human condition. But I don’t think it has to be as highfalutin as Everest or as Antarctica, you know.

In many of our films, we’ve seen people come away and say that by watching them, they’re thinking more deeply about their life intentions and things they want to do, like asking a girl out for example. What’s the worst that can happen? Someone can say no.

It’s clear that ‘Endurance’ is so much more than just the name of Shackleton’s ship. What do you hope the audience takes away from the concept of ‘endurance’ in your film? Should we work harder at becoming more enduring?

I’m not one to judge anyone else’s ability to endure anything because there are a lot of people who endure a lot silently and suffer, for example, especially if you look at the history of female kind. But it’s a good question.

It is amazing that Shackleton’s Endurance crew navigated their way out, and endured such conditions. I’m really struck by the civility and the grace of everyday life they maintained on the ice. They put on their plays, read books and listened to music while on the expedition – to keep that sense of humanity.

Endurance asks questions about how we connect with one another, the kinds of kindness we can show one another, where one can find strength when everything is done.

There are lots of psychological and emotional questions around, but I think the point is that human beings are pretty freaking tough.

Have you got any future projects in the pipeline?

Our next film coming out is a film on the story of the plane carrying an Indigenous family that crashed in the Amazon last May. The mother was killed on impact, and the four children were left in the Amazon and lost for 40 days.