Rewilding projects across Europe are working to expand populations of carnivores and restore ‘self-regulating’ nature on the continent. In the face of the double-trouble of limited space and a lot of people, proponents are coming up with new ways to create a wilder landscape, formulating a rewilding philosophy fit for a European context

By

Natural Europe isn’t what it once was. Forty thousand years ago, modern humans arrived. The megafauna that inhabited Europe’s grasslands and forests were faced with an unfamiliar and unforgiving threat. Europe’s cave bears, sabretooths, hyaenas, cave lions, woolly rhinos and mammoths were swiftly extirpated by this hyper-cooperative biped. Relict populations of wolves, bears and lynx were the only survivors.

The decline of Europe’s carnivore populations reached its nadir in western, central and northern Europe during the 19th and early 20th centuries, as agricultural and industrial upscaling saw their habitats converted to farmland. Persecution was sometimes encouraged. ‘Up until the 1960s, the Spanish government paid bounties for the killing of Iberian wolves and lynxes,’ says Carlos Bautista, a researcher at the Institute of Nature Conservation at the Polish Academy of Sciences.

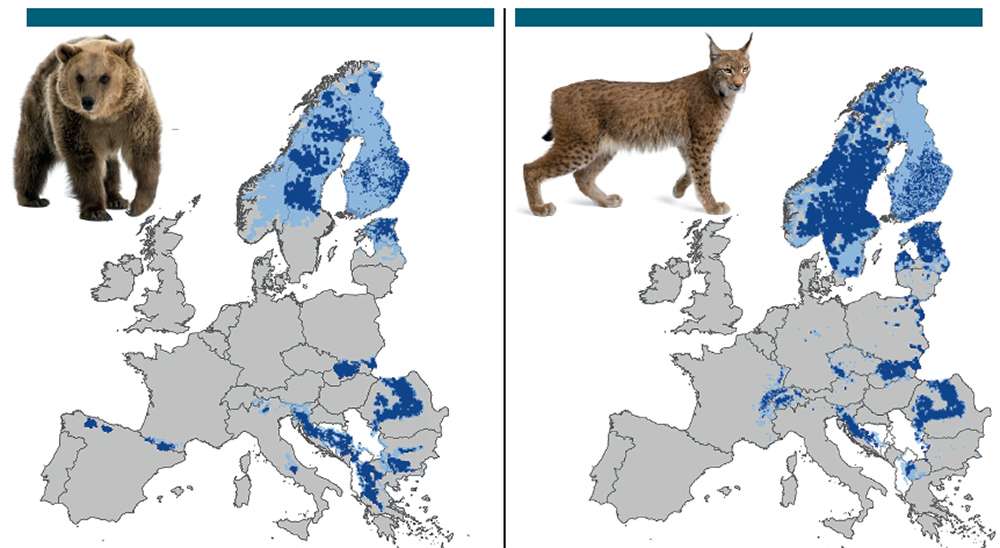

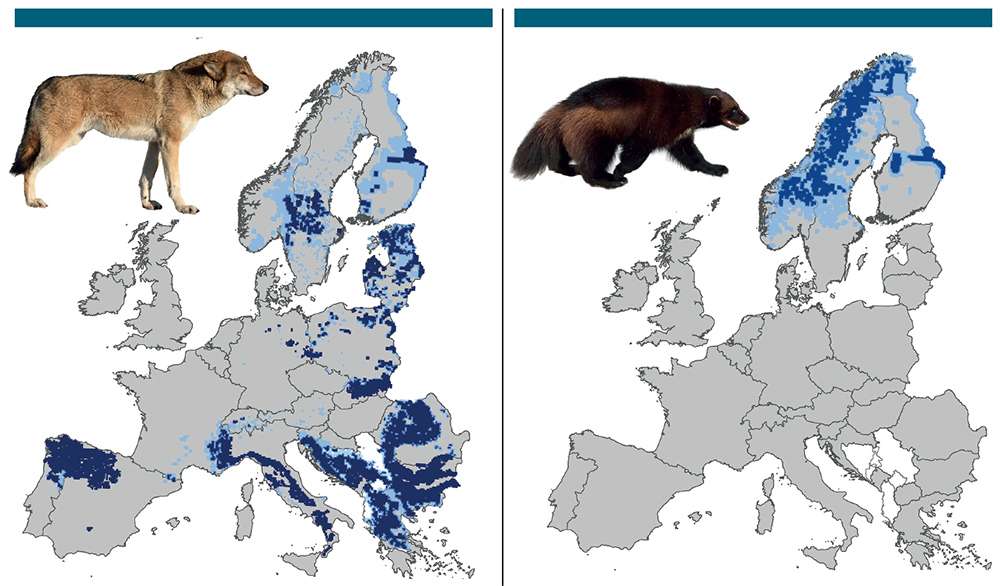

As the 20th century whirred, shifts in public opinion towards wildlife conservation saw the Bern Convention enter into force in 1979, legally protecting bears, wolves, lynx and wolverines. Large-scale rural–urban migration reduced land pressures, while the advent of sustainable forestry offered more habitat for both predator and prey. Wolves have now recolonised parts of Scandinavia, Finland, France, Switzerland, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands; bears have been reintroduced in Austria and small populations transported to the French Pyrenees and Italian Alps from Slovenia; lynx have been reintroduced to select sites in their historic range. Numbers of European carnivores are on the up, estimated at around 17,000 brown bears, 12,000 wolves, 9,000 Eurasian lynx and 1,200 wolverines.

As we enter the third decade of the 21st century, Europeans are now evaluating their relationship with nature. The Large Carnivores Initiative for Europe – the IUCN’s specialist group on the subject – has set out a manifesto for the long-term conservation of carnivores, based on three central premises: that ‘large carnivores have a right to inhabit Europe’; that ‘Europe is a better, richer, and more diverse place with large carnivores and the role they play in functional ecosystems’; and that ‘future generations should be able to experience large carnivores as an integral part of our European natural heritage’.

At the same time, ‘rewilding’ has become a well- known philosophy. The approach centres on the belief that restoring functional ecosystems will allow them to become self-regulating, reducing the need for human intervention. Large carnivores are one part of the puzzle. Much of Europe’s native fauna has evolved in the presence of predators. Wolves, bears and lynx all regulate herbivore densities, in turn allowing vegetation to cycle and forests to regenerate. ‘All levels of the trophic chain should be present for an ecosystem to function at maximum capacity – in much of Europe, this means having old-growth forests, deadwood, herbivores and carnivores,’ says Bautista. ‘The main goal of rewilding, whether or not you like the term, is to restore lost ecosystem functions.’

The movement now has big backing: the LIFE programme – the EU’s funding instrument for the environment and climate action – had a budget of €3.4 billion between 2014 and 2020. Rewilding Europe, a network of land-management and conservation initiatives, is a major beneficiary of the programme.

A range of rewilding projects have emerged across the continent in recent years. Rewilding Europe has 61 initiatives in its European Rewilding Network, together protecting five million hectares of land, spanning 27 European countries. Their mission: to make Europe a ‘wilder place’, with more space for wildlife and natural processes. Yet, while the rewilding movement has reinvigorated public interest in Europe’s natural history, restoring lost ecosystem functions in a human-dominated landscape – especially at a scale where they can become self-regulating – is no easy undertaking.

Room to grow

‘Carnivores need to have a genetically viable population, one that can successfully interbreed with other connected populations,’ explains Tom Ovenden, an ecologist at Stirling University. ‘They need room to expand and grow.’ Unfortunately, this isn’t always possible. The largest populations of European carnivores reside in the Carpathian, Scandinavian, Baltic and western Balkan regions – many (25 of the 33 largest populations) cross national borders and are free to breed and exchange genes with connected populations. But some populations, such as those of the Iberian wolf and Italy’s Marsican brown bear, and also many lynx populations, are more fragmented.

The problem is compounded by the fact that site selection for Natura 2000 – Europe’s protected-area network – is delegated at the national level, leading to poorly coordinated sites that are rarely assessed for connectivity. Portugal’s Iberian wolf typifies this conservation conundrum. An estimated 50 animals live in the Greater Côa Valley, but the Douro River currently separates wolves in the Malcata mountain range in the south from those in the larger Douro valley to the north. In order to improve genetic diversity, the wolves need a protected corridor to connect the two isolated sub-populations.

Rewilding advocates are seizing a rare opportunity to expand this wolf population. In 2019, Rewilding Portugal, along with other Portuguese partners and Rewilding Europe, launched the five-year LIFE WolFlux project, a €2.2 million collaboration with local landowners that aims to convert abandoned rural land into a 120,000-hectare protected corridor for the wolves. ‘In the Greater Côa Valley, people are abandoning agricultural land, which is creating an opportunity for nature to thrive,’ says Sara Aliacar, conservation officer for Rewilding Portugal. Boosting predators is just one part of the rewilding effort in the region. Horses and native-breed cattle are also being released as ‘grazing fire-prevention squads’, keeping wildfires at bay by clearing dry shrubs.

Similar efforts are underway to expand a fragile population of Marsican brown bears in the Central Apennines. The 60 remaining individuals are currently restricted to an area of land of between 1,500 and 2,500 square kilometres. Rewilding Apennines is working with local organisation Salviamo l’Orso, which has identified a further 10,000 square kilometres of suitable habitat. Together, the groups aim to establish four wildlife corridors, increasing the bears’ range to 275,000 hectares. ‘Marsican brown bears have helped to shape the landscape. They eat fruits and distribute their seeds across the region, spreading plant genes,’ says Mario Cipollone, who leads the Rewilding Apennines team. ‘They complete the circle of life by feeding on and leaving carcasses, which support vast amounts of scavengers and plant and insect life.’

Many ecologists welcome the growth in space for the Iberian wolf and the Marsican brown bear. Yet, with their ranges still restricted, there are concerns that the scale of rewilding projects is still too small to fully restore carnivores into the natural feedback loops that regulate ecosystems. ‘The impacts of humans on habitats, herbivores and carnivores is so pervasive [in Europe] that there are simply no areas large enough for natural processes such as carnivory and herbivory to occur without a major impact of human activity on all trophic levels [of the ecosystem],’ says ecologist Luigi Boitani, a leading authority on wolves and emeritus professor at the Sapienza University of Rome.

It’s for this reason that there are some who feel that the very term ‘rewilding’ may not be appropriate, particularly in Europe were the ‘wild’ is long gone. John Linnell, a senior research scientist at the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, admires the mission but also questions whether a state of self-regulating nature can be achieved. ‘The processes that govern large species happen on much larger scales than those embraced by any rewilding site so far, making it impossible to internalise the self-regulation of all trophic levels (vegetation–herbivore–carnivore) into single sites,’ he says.

Nevertheless, Linnell believes the movement still has its upsides. ‘Rewilding has brought a lot of fresh energy into a stagnated conservation field,’ he adds. ‘Without the space, rewilding efforts can’t quite be as hands-off as people assume – you will have to tinker with many parts of the ecosystem to restore it. But, I am tempted to say that if the outcome is net positive, call it whatever you like.’

Howl of the wolf

The Scottish Highlands used to be home to lush pine forests patrolled by bears, wolves and lynx. In mainland Europe, some predators have been returning to their historic homelands by themselves, but they can’t swim the channel. ‘If we give them a helping hand, large carnivores can help to restore Scotland’s landscape,’ says Paul Lister, a passionate proponent of rewilding and founder of The European Nature Trust.

In 2003, Lister purchased 23,000 acres of denuded land just north of Inverness. Overgrazing by an unchecked deer population had rendered the land barren and without much of the forest of old. The land is now Alladale Wilderness Reserve, where some 1 million native trees have been planted; red squirrels have been reintroduced and golden eagle numbers have soared. The culmination of the plan is to reintroduce wolves, albeit with the UK’s size very much in mind. ‘Releasing a load of wolves is not a very sensible thing to do at the moment,’ says Lister. ‘But bringing them back into a fenced reserve of 50,000-plus acres could be a solution. That would allow you to have controls, to measure ecological impacts and to gauge societal attitudes.’ Lister urges a shake-up of our relationship with nature in Europe. ‘The big question is, are we prepared to start the process of change? Are we prepared to see Europe become a properly functioning landscape again?’

Walking with carnivores

In the Southern Carpathian mountain range in Romania, which supports lynx, brown bears and grey wolves, Rewilding Europe and WWF Romania are creating one of the largest contiguous wild areas in Europe. They hope to extend a backbone of more than a million hectares into a further three million hectares of rewilded land. However, in doing so, they’ve had to counter another major challenge of rewilding – reducing human–wildlife conflict.

In 2011, European countries handed out €28.5 million to local communities in compensation for damage done by wildlife. The average cost of an individual carnivore over the period of 2004–12 was more than €6,300 for wolverines, €2,400 for wolves, €1,800 for bears and €700 for lynx. A quarter of this compensation was given out in Norway, where, in 1999, certain areas were designated to allow wolves to roam freely, albeit with a limit on numbers. The government lethally controls wolf populations that rise above that limit or venture too far afield.

Poaching also remains a problem. Italy’s 60 Marsican brown bears are classified as critically endangered by the IUCN, but three bears were killed per year between 1975 and 1985, with poaching accounting for 60 per cent of deaths. In November 2007, destruction of livestock motivated the killing of three brown bears and five wolves in the area. Reintroduction campaigns often lead to polarised opinions. In 2000, 30 years after the reintroduction of lynx to the eastern Alps in Switzerland in the 1970s, the Bern Environmental Office received a package containing the paws of a lynx and a postcard stating that the gift had come from the ‘Bern hunting jungle’. In 1996, fierce demonstrations broke out in response to efforts to reseed struggling bear populations in the Pyrenees; key supporters received death threats and a local mayor was even taken hostage.

‘Reintroductions, translocations and rewilding projects with large carnivores are 80 per cent sociology and 20 per cent ecology,’ says Boitani, who would love nothing more than for the public to coexist with wildlife. ‘The public must understand that rewilding efforts will see more natural dispersion and populations will naturally grow.’

‘When large carnivores are in a shared landscape, conflicts are inevitable and some kind of human intervention will be necessary to manage them,’ adds Linnell. He points out that rewilding initiatives must tread carefully. ‘Almost all land in Europe is either private or belongs to the state or a forest-management company, so if you’re rewilding on a scale that’s bigger than your own farm, you can encounter problems with settled communities, where their interests don’t always align with conservation goals. There is, rightly, a discourse about finding a sustainable relationship with the land we live in, but some rural communities have viewed rewilding efforts as anti-human.’

In light of these difficulties, rewilding initiatives are approaching conflicts differently, trying to diffuse tensions before they arise. In the Apennines, Rewilding Europe and Salviamo l’Orso are hoping that close consultation with local stakeholders and formal designation of ‘coexistence corridors’ will drive down bear mortality. Twenty-one electric fences have been installed; bear-proof organic-waste bins have been provided; and 90 per cent of local farms have been secured from bear access. Subsequently, between 2015 and 2017, Rewilding Europe recorded a 98 per cent reduction in bear incidents in the region. For Mario Cipollone, leader of the Central Apennines rewilding team, prevention trumps reparation. ‘We want bear and wolf populations to grow in the Central Apennines, so we’re proactively working with local people to prevent damage,’ he says. ‘We can smooth out this divide between communities and conservationists, and in turn build coexistence with carnivores.’

Some of these coexistence strategies aren’t new, but simply rekindle age-old traditions of living with carnivores. Shepherds in Portugal’s Greater Côa Valley can now expect to receive ‘guard-dog’ puppies as part of the LIFE WolFlux project. The Serra da Estrela dogs are integrated into sheep flocks to protect them from wolves – a tradition lost with the decline of wolf populations through the mid-20th century.

The missing lynx

Since 1971, 15 reintroductions of Eurasian lynx have been carried out in an attempt to revive populations in Scandinavia, the eastern Baltic drainage, the Carpathians and the south-western Balkans. Tactics and successes have varied: five reintroduced populations managed to breed and these now make up half of the ten Eurasian lynx populations currently in existence.

The successful restoration of wolf populations in Yellowstone National Park in 1995 renewed calls for the lynx to be reintroduced to other areas. In particular, Scotland has a similar problem to that found in Yellowstone: red and roe deer numbers reached a high of 783,000 in 2013, resulting in the culling of 135,000 individuals in 2017. ‘Deer hammer forest regeneration. There’s a feeling that the Highlands are not coated in trees because of overgrazing,’ says Tom Ovenden, an ecologist at Stirling University.

Nevertheless, any reintroduction will be done with caution. ‘The Yellowstone reintroduction of wolves captured ecologist’s attention with the power of restoring top–down trophic cascades, but that doesn’t mean it will be replicable in the Scottish landscape,’ says Ovenden. ‘Reintroductions need to be based on an accurate understanding of specific ecological and sociological contexts – there’s a lot of work still to be done to understand the unique ecology and attitudes of local communities in the Highlands.’

A more modern culture of tolerance might also be built through local wallets. The LIFE Bison project is working to reintroduce bison to the Southern Carpathians, also home to bears, wolves and lynx. Bison reintroduction brings a diversification of employment opportunities in rural Romania. A refurbished visitor centre in the small town of Armenis is the heart of the area’s wildlife tourism, with ‘wilderness cabins’ dotting the nearby hills. Bison- and carnivore-based tourism packages are marketed and sold through the European Safari Company. ‘More than 100 families are supported by revenue from bison- and bear-tracking activities, providing services from catering to transport to accommodation,’ says Bianca Stefanut of WWF Romania, collaborators with Rewilding Europe. ‘Households have transformed their old hamlets into rustic Airbnbs.’

The rewilding movement even has its own investment programme. Last year, Rewilding Europe Capital gave a €600,000 loan to a Portuguese nature-based tourist resort in the Greater Côa Valley; two loans have also expanded the Bisegna Mountain Refuge in the Central Apennines, where it’s hoped that the local bears and wolves will lure tourists. ‘A lot of the archaeological heritage in the Central Apennines region has been destroyed by earthquakes. Historically, we’ve had very few tourists. Now, the bears in Abruzzo National Park are bringing new opportunities for tourism,’ says Cipollone.

Frans Schepers, managing director of Rewilding Europe, is convinced that building economies around wildlife can incentivise coexistence. ‘In the Greater Côa Valley, the outskirts of the Central Apennines and much of the Southern Carpathians, rural land abandonment has created difficulties for local economies,’ he says. ‘Protecting iconic species through a philosophy of restoring wild nature can provide alternative income.’

Paradigm shift

Rewilding has attracted critics for its potentially impossible promise to restore wilderness on a continent that has very little in the way of human-free space. ‘I don’t think there’s much to be gained from viewing conservation as the preservation of a single moment in time. That’s dangerous under a rapidly changing climate,’ says Ovenden.

Yet, language aside, the popularity of the rewilding movement has reinvigorated a desire to live more sustainably with wildlife. Coexistence strategies are gaining traction, nature-based economies are popping up and Europe is establishing itself as a destination for wildlife lovers. Linnell admits it might be time for a paradigm shift: ‘I increasingly think that nature conservation is a social movement. I don’t always think that it needs to be motivated by scientific evidence alone – it can simply be about beauty, moral values and ethics.’ Rewilding professionals are keen to make their intensions clear. ‘Carnivore restoration represents a small part of the rewilding movement. It’s not about going back to the idyllic past, bringing back individual species, or establishing vast areas of wilderness,’ says Schepers. ‘It’s about a more holistic way to approach European conservation in the 21st century.’