Using computer simulations, cultural evolution researcher Alex Mesoudi analyses the impact of migration and challenges the belief that it harms a host country’s cultural identity

By Alex Mesoudi

Few political and social issues generate as much passion and controversy as immigration. One of the most prominent concerns among anti-immigration campaigners is the idea that immigration breaks down the host society’s cultural traditions and harms its cultural identity. But is that the case?

Central to these debates is what academics call ‘acculturation’. This term refers to behavioural or psychological changes in immigrants (or their descendants) that follow migration. They are typically changes that make behaviour or ways of thinking more similar to members of the adopted society. Politicians such as Nigel Farage argue that immigrants do not adequately acculturate, at least at certain levels of immigration. But this is an empirical question and has been addressed by many economists and social scientists.

In a recent study, I reviewed the evidence on acculturation, including my own work with British Bangladeshis in East London. These studies typically measure behavioural or psychological traits in first generation migrants (who moved to another country after the age of 14), second generation migrants, and non-migrants who have been living in the host area for several generations. They look at whether people value work or family, whether people explain others’ actions in terms of dispositions (laziness) or situations (lack of support), and prosocial acts such as giving to charity. Such traits often vary between the migrants’ country of origin and their adopted country.

The evidence suggests that acculturation is common, but generational. While first generation migrants typically retain the values of their society of origin, later generations shift about 50 per cent of the way from their parents’ values towards non-migrant values. This even occurs in communities that form large, cohesive minorities. British Bangladeshis make up 32 per cent of Tower Hamlets, yet second generation British Bangladeshis fall half way between their parents and non-migrants on psychological measures.

Stay connected with the Geographical newsletter!

In these turbulent times, we’re committed to telling expansive stories from across the globe, highlighting the everyday lives of normal but extraordinary people. Stay informed and engaged with Geographical.

Get Geographical’s latest news delivered straight to your inbox every Friday!

To explore these dynamics, I created a series of computer simulations to ask what level of acculturation is needed to maintain the host’s distinct cultural traditions in the face of different levels of migration. I simulated multiple ‘societies’, each with distinct cultural traits, allowed a certain number of virtual ‘people’ to migrate from society to society, and specified a certain likelihood that they would ‘acculturate’, or switch from their original cultural trait to the most common cultural trait in their new society.

The simulations showed that migration with no acculturation breaks down distinct host cultures. This is the scenario envisioned by anti-immigration campaigners. Even a little migration, without acculturation, soon creates a homogeneous worldwide blend of the cultural traits that were originally unique to different societies.

But adding just a small amount of acculturation to the simulations could preserve cultural differences. For example, even for relatively high migration rates where ten per cent of the society migrates in each time period, just a 20 per cent probability of acculturation is needed to maintain distinct cultural variation between societies. This suggests that the 50 per cent acculturation level observed in the real-world is strong enough to preserve distinct cultures.

These results held for both ‘neutral’ traits such as dress or dance, and for costly cooperative traits, such as building bridges or paying taxes, where individuals pay initial costs to benefit the entire society. Much concern over immigration centres on the latter – that immigrants take benefits without paying costs.

There were, however, levels of migration at which no level of acculturation could preserve cultural traditions. When 50 per cent or more of the societies migrate, then distinct traditions cannot be maintained. While this exceeds modern levels of migration, we might think of historical cases of colonisation (the New World by Europeans) as examples where high levels of migration broke down traditions.

My aim with this research was to try to inform public and political debates on the effects of immigration on cultural identity, which to me often proceed with little empirical basis. Combining my review of the evidence with my computer simulations, it seems to me that real-life levels of acculturation are easily strong enough to prevent immigration from destroying host national identities, contrary to the claims of Farage and others. It also highlights the need for much more research on acculturation. We don’t really know how it works and my research has not addressed the benefits that immigrants can bring to their adopted societies.

Whatever future research finds, it would surely be better if immigration policy and media coverage of immigration, were better informed by the available evidence concerning migrant acculturation.

Alex Mesoudi is an associate professor of cultural evolution in the Human Behaviour and Cultural Evolution Group at the University of Exeter.

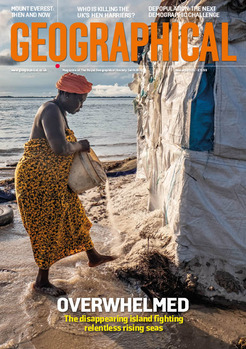

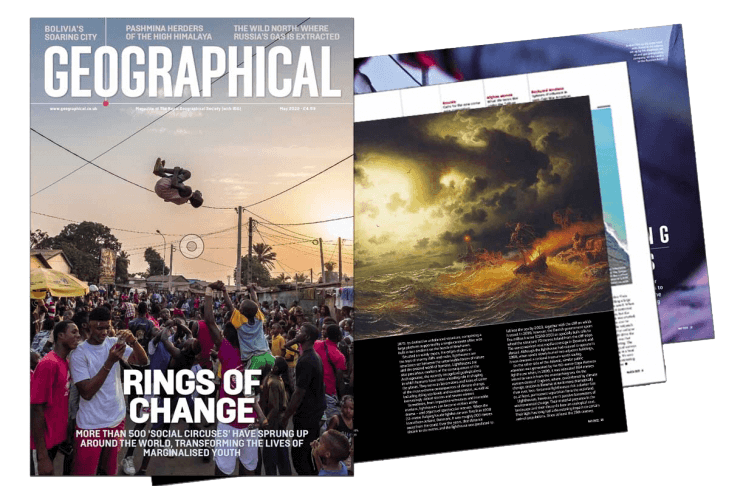

Subscribe to our monthly print magazine!

Subscribe to Geographical today for just £38 a year. Our monthly print magazine is packed full of cutting-edge stories and stunning photography, perfect for anyone fascinated by the world, its landscapes, people and cultures. From climate change and the environment, to scientific developments and global health, we cover a huge range of topics that span the globe. Plus, every issue includes book recommendations, infographics, maps and more!